1. Introduction

What are the levels of studentsÔÇÖ pre-interest, English language achievement, interactions with professors, and cultural understanding and interest in online liberal arts English classes, including Reading, Listening, and Speaking I and II?

How are pre-interest and cultural understanding related to studentsÔÇÖ level of English language achievement in each English class?

Lastly, to what extent do pre-interest, English language achievement, and interactions with professors in each English class affect studentsÔÇÖ cultural understanding and interest?

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role of Culture in Foreign Language Education

2.2. The Role of the Classroom on Learning Foreign Language

2.3. The Role of Online EFL Classes and Foreign Culture Learning

3. Methods

3.1. Research Participants

<Table 1>

| Name of class | Number of participants | Number of classes | Number of professors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Listening | 447 | 16 | 6 |

| Reading | 556 | 24 | 5 |

| Speaking I | 363 | 37 | 8 |

| Speaking II | 55 | 7 | 5 |

| Total | 1421 | 84 | 24 |

3.2. Research Materials and Processes

3.2.1. Online English Classes

3.2.2. Survey Questions

<Table 2>

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. What are the Levels of StudentsÔÇÖ Pre- interest, English Language Achievement, Interactions with Professors, and Cultural Understanding and Interest in Online Liberal Arts English Classes, Including Reading, Listening, and Speaking I and II?

<Table 3>

| Questions | Area | Total | M | SD | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Pre-interest in English | Interested in this class and applied for the class | Listening | 447 | 3.80 | 1.050 | 3.217 | 0.007** |

| Reading | 556 | 3.91 | 0.956 | 6.045 | 0.000*** | ||

| Speaking I | 363 | 4.06 | 0.962 | 4.796 | 0.000*** | ||

| Speaking II | 55 | 4.53 | 0.663 | 0.983 | 0.426 | ||

| Ready to work hard on the tasks | Listening | 447 | 4.20 | 0.864 | 3.809 | 0.002** | |

| Reading | 556 | 4.24 | 0.810 | 8.698 | 0.000*** | ||

| Speaking I | 363 | 4.43 | 0.679 | 2.970 | 0.005** | ||

| Speaking II | 55 | 4.71 | 0.567 | 0.742 | 0.569 | ||

| 2) Language achievement | I can listen and summarize / I can read and understand / I can express my thoughts | Listening | 447 | 3.95 | 0.838 | 1.661 | 0.143 |

| Reading | 556 | 4.10 | 0.820 | 6.466 | 0.000*** | ||

| Speaking I | 363 | 4.06 | 0.880 | 7.984 | 0.000*** | ||

| Speaking II | 55 | 4.18 | 0.905 | 0.312 | 0.868 | ||

| 3) Interactions with professors | Interacted with the professor in various ways (Q&A, feedback) | Listening | 447 | 3.34 | 1.162 | 3.053 | 0.010* |

| Reading | 556 | 3.27 | 1.237 | 15.403 | 0.000*** | ||

| Speaking I | 363 | 3.92 | 1.124 | 5.650 | 0.000*** | ||

| Speaking II | 55 | 4.29 | 0.913 | 1.599 | 0.192 | ||

| 4) Cultural understanding and interest | Understand differences in communication methods and values between cultures | Listening | 447 | 3.74 | 1.051 | 54.910 | 0.000*** |

| Reading | 556 | 3.73 | 0.990 | 23.477 | 0.000*** | ||

| Speaking I | 363 | 4.02 | 0.949 | 4.732 | 0.000*** | ||

| Speaking II | 55 | 4.38 | 0.707 | 0.760 | 0.557 | ||

| Became interested in the social, cultural, and economic environment of other countries | Listening | 447 | 3.74 | 1.058 | 41.225 | 0.000*** | |

| Reading | 556 | 3.80 | 1.023 | 22.084 | 0.000*** | ||

| Speaking I | 363 | 4.09 | 0.933 | 2.944 | 0.005** | ||

| Speaking II | 55 | 4.47 | 0.716 | 0.445 | 0.776 | ||

1) Pre-interest in English: The first section of the table presents the results of studentsÔÇÖ pre-interest in English language learning, specifically their interest in the class, willingness to work hard on tasks, and their ability to express their opinion to others. The data shows that students who applied for the class had a higher mean score in Listening (3.80) and Reading (3.91) compared to Speaking I (4.06) and Speaking II (4.53). The results also indicate that students were ready to work hard on tasks, with a mean score of 4.20 in Listening, 4.24 in Reading, 4.43 in Speaking I, and 4.71 in Speaking II. The F-values and p-values indicate that these differences in mean scores between the four areas are statistically significant.

2) Language achievement: The second section of the table presents the results of studentsÔÇÖ language achievement in listening comprehension, reading comprehension, and their ability to express their opinion to others. The data shows that students had a higher mean score in speaking II (4.18), reading comprehension (4.10), and in speaking I (4.06) compared to listening comprehension (3.95). The F-values and p-values indicate that the difference in mean scores between the areas of reading comprehension and expressing their opinion to others are statistically significant.

3) Interactions with professors: The third section of the table presents the results of studentsÔÇÖ interactions with professors, specifically how they interacted with the professor in various ways for question- and-answer and feedback. The data shows that students had a higher mean score in speaking II (4.29) compared to Listening (3.34), Reading (3.27), and Speaking I (3.92). The F-values and p-values indicate that the differences in mean scores between the four areas are statistically significant.

4) Cultural understanding and interest: The fourth section of the table presents the results of studentsÔÇÖ cultural understanding and interest, specifically their ability to understand differences in communication methods and values between cultures and their interest in the social, cultural, and economic environment of other countries. The data shows that students had a higher mean score in Speaking II (4.38) compared to Listening (3.74), Reading (3.73), and Speaking I (4.02) for the first question. The data also shows that the students generally felt that it was possible to understand differences in communication methods and values between cultures. The mean scores for Listening and Reading were both around 3.74, indicating that the respondents felt somewhat confident in their ability to understand these differences. However, the mean score for Speaking I was higher at 4.02, suggest- ing that the respondents felt more confident in their ability to communicate effectively across cultures when speaking. The mean score for Speaking II was the highest at 4.38, indicating that the respondents felt very confident in their ability to communicate across cultures in more advanced speaking situations. The p-values for all items were very low, indicating that the results are statistically significant.

<Table 4>

1) Pre-interest in English: In terms of pre-interest in English, the results show that the majority of students were interested in the class and applied for it. For Listening, 274 students (61.29%) agreed or strongly agreed that they were interested in the class, while 274 students (61.29%) also agreed or strongly agreed that they were ready to work hard on the tasks required. Similarly, for Reading, 367 students (65.93%) agreed or strongly agreed that they were interested in the class, while 458 students (82.30%) agreed or strongly agreed that they were ready to work hard on the tasks required. In Speaking I, 285 students (78.51%) agreed or strongly agreed that they were interested in the class, while 326 students (89.84%) agreed or strongly agreed that they were ready to work hard on the tasks required. For Speaking II, although the number of responses was relatively low, the majority of students (76.36%) indicated their agreement or strong agreement with being interested in the class. Furthermore, a significant proportion of students (94.55%) reported that they were ready to work hard in the class.

2) Language achievement: Regarding language achie- vement, the results show that the majority of students were able to listen to others and summarize the core contents, read and understand the core contents, and express their thoughts or opinions with others. For Listening, 309 students (69.13%) agreed or strongly agreed that they could listen to others and summarize the core contents. Similarly, for Reading, 430 students (77.34%) agreed or strongly agreed that they could read and understand the core contents. In Speaking I, 279 students (76.86%) agreed or strongly agreed that they could express their thoughts or opinions with others. For Speaking II, the number of responses was relatively low, but the majority of students (74.54%) agreed or strongly agreed that they could express their thoughts or opinions with others.

3) Interactions with professors: Regarding interactions with professors, the results show that the majority of students interacted with the professor in various ways, such as online, for question-and-answer and feedback during the semester. Although there are variations in the percentages for different categories, such as in Speaking I where 255 students (70.33%) agreed or strongly agreed that they engaged with the professor through various means. For Speaking II, the number of students was relatively low, but a majority of students (80.00%) agreed or strongly agreed that they interacted with the professor in various ways.

4) Cultural understanding and interest: Regarding cultural understanding and interest, the results show that the majority of students found it possible to understand differences in communication methods and values between cultures through the class. For Listening, 276 students agreed or strongly agreed that it was possible to understand differences in communication methods and values between cultures, while 271 students agreed or strongly agreed that they became interested in the social, cultural, and economic environment of other countries through the class. Similarly, for Reading, 319 students agreed or strongly agreed that they were able to understand differences in communication methods and values between cultures, while 333 students agreed or strongly agreed that they became interested in the social, cultural, and economic environment of other countries through the class. Additionally, for Speaking 1, 266 (73.28%) students agreed or strongly agreed that they were able to understand differences in communication methods and values between cultures, while 276 (76.03%) students agreed or strongly agreed that they became interested in the social, cultural, and economic environment of other countries through the class. In Speaking II, even though the number of students was relatively low, a significant majority of students (87.27%) agreed or strongly agreed on both questions related to cultural understanding and interest. The frequency analysis data shows that the class was effective in promoting cultural understanding and interest among the students as the majority found it possible to understand differences in communication methods and values between cultures and became interested in the social, cultural, and economic environment of other countries.

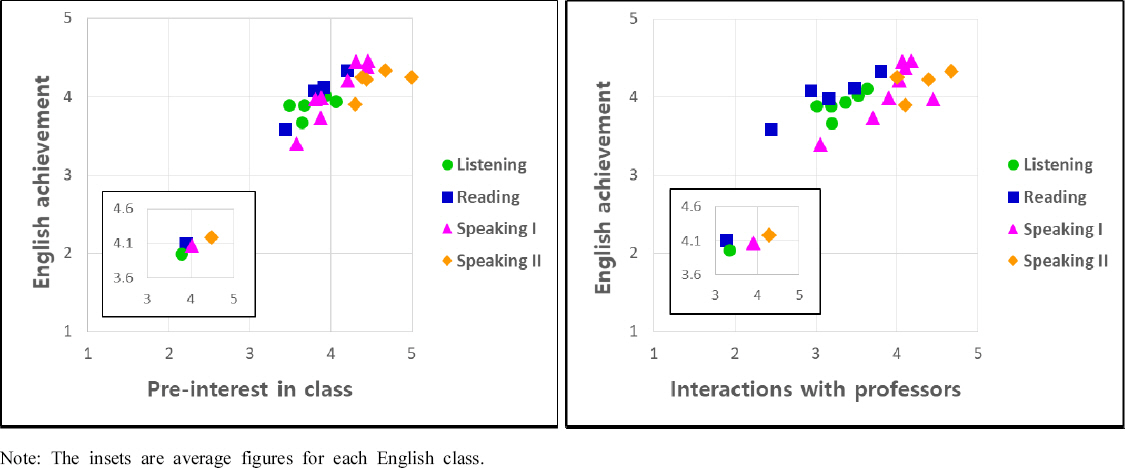

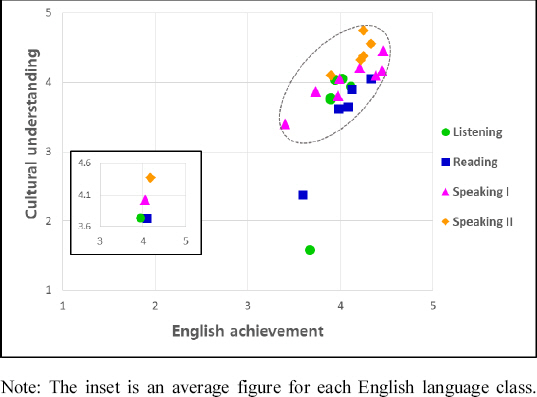

4.2. How are Pre-interest and Cultural Understanding Related to StudentsÔÇÖ Level of English Language Achievement in Each English Elass?

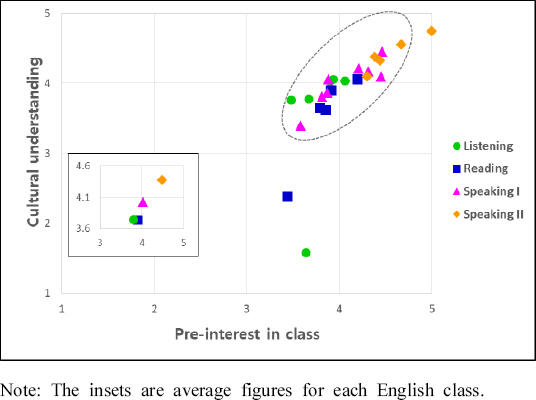

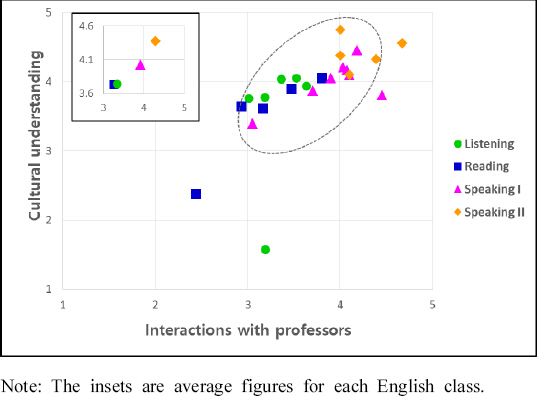

[Figure 2]