|

|

- Search

| Korean J General Edu > Volume 16(4); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

This study investigated how EFL teachers at a Korean university perceived the introduction of post COVID restrictions and protocols during their classes during the transition from online classes to in-person classes in the spring of 2022. Data were collected from 17 teachers employed at a private university in the greater Seoul area. A survey questionnaire consisting of multiple choice, Likert scale and open- ended questions was used as the initial data collection method. In addition, survey participants who consented were contacted by e-mail to discuss responses in greater detail. Data was analyzed using general qualitative analysis and discussed using descriptive statistics. The findings show that despite the restrictions, teachers were generally able to continue their teaching duties but there were high levels of frustration with the limited number of pedagogical options available to them. In addition, they view masks and socially distancing as a significant hindrance to communication, classroom engagement, and performance. Administrational and educational implications of these findings as well as limitations are also discussed.

Abstract

в│И ВЌ░Жхгвіћ ЖхГвѓ┤ вїђьЋЎВЮў EFL ЖхљВѓгвЊцВЮ┤ 2022вЁё в┤ё ВўевЮ╝ВЮИ ВѕўВЌЁВЌљВёю ВІцВаё ВѕўВЌЁВю╝вАю ВаёьЎўьЋўвіћ Ж│╝ВаЋВЌљВёю ВѓгьЏё ВйћвАювѓў ВаюьЋюЖ│╝ ьћёвАюьєаВйюВЮў вЈёВъЁВЮё Вќ┤вќ╗Ж▓ї ВЮИВІЮьќѕвіћВДђ ВА░ВѓгьЋўВўђвІц. ВёюВџИ ВДђВЌГВЮў ьЋю Вѓгвдй вїђьЋЎВЌљ Ж│аВџЕвљю 17вфЁВЮў ЖхљВѓгвЊцвАювХђьё░ вЇ░ВЮ┤ьё░Ж░ђ ВѕўВДЉвљўВЌѕвІц. В┤ѕЖИ░ вЇ░ВЮ┤ьё░ ВѕўВДЉ в░Ев▓ЋВю╝вАювіћ Ж░ЮЖ┤ђВІЮ, вЮ╝ВЮ┤В╗цьіИ В▓ЎвЈё, Ж░юв░ЕьўЋ ВДѕвгИВю╝вАю ЖхгВё▒вљю ВёцвгИВДђЖ░ђ ВѓгВџЕвљўВЌѕвІц. вўљьЋю, вЈЎВЮўьЋю ВёцвгИ ВА░Вѓг В░ИЖ░ђВъљвЊцВЌљЖ▓ї вЇћ ВъљВёИьЋю вІхв│ђВЮё вЁ╝ВЮўьЋўЖИ░ ВюёьЋ┤ ВЮ┤вЕћВЮ╝ВЮё ьєхьЋ┤ ВЌ░вЮйвљўВЌѕвІц. вЇ░ВЮ┤ьё░віћ ВЮ╝в░ўВаЂВЮИ ВаЋВё▒ вХёВёЮВЮё ВѓгВџЕьЋўВЌг вХёВёЮьЋўЖ│а ЖИ░Вѕа ьєхЖ│ёвЪЅВЮё ВѓгВџЕьЋўВЌг вЁ╝ВЮўьЋўВўђвІц. ВЌ░Жхг Ж▓░Ж│╝віћ ВЮ┤вЪгьЋю ВаюьЋюВЌљвЈё вХѕЖхгьЋўЖ│а, ВёаВЃЮвІўвЊцВЮђ ВЮ╝в░ўВаЂВю╝вАю ЖиИвЊцВЮў ЖхљВДЂ ВЌЁвг┤вЦ╝ Ж│ёВєЇьЋа Вѕў ВъѕВЌѕВДђвДї, ЖиИвЊцВЮ┤ ВЮ┤ВџЕьЋа Вѕў Въѕвіћ ЖхљВюАВаЂ ВёаьЃЮВЮў ВаюьЋювљю ВѕФВъљВЌљ вїђьЋ┤ вєњВЮђ ВѕўВцђВЮў ВбїВаѕЖ░љВЮ┤ ВъѕВЌѕвІцвіћ Ж▓ЃВЮё в│┤ВЌгВцђвІц. Ж▓ївІцЖ░ђ, ЖиИвЊцВЮђ вДѕВіцьЂгВЎђ ВѓгьџїВаЂ Ж▒░вдгвЉљЖИ░вЦ╝ ВЮўВѓгВєїьєх, ЖхљВІц В░ИВЌг, ЖиИвдгЖ│а ВѕўьќЅВЌљ ВъѕВќ┤ ВцЉВџћьЋю ВъЦВЋавг╝вАю Ж░ёВБ╝ьЋювІц. ВЮ┤вЪгьЋю в░юЖ▓гВЮў ьќЅВаЋВаЂ, ЖхљВюАВаЂ ВЮўв»ИВЎђ ВаюьЋю ВѓгьЋГвЈё вЁ╝ВЮўвљювІц.

Following the easing of COVID-19 related social distancing restrictions in early 2022, a number of universities in South Korea began to resume face-to-face lessons after 2 years of online instruction being the norm. Despite a large surge in new cases in January and February due the omicron variant, with approximately 80% of the adult population (Jeong, 2021) being fully vaccinated, and an increased understanding of how to treat the virus, the ministry of education (MOE) gave the go-ahead for the return to in- person classes. However, it was not as simple as returning to campus for pre-COVID style lessons. The risk of infection was still high with both the number of daily new cases and number of daily deaths reaching their highest peak of the pandemic in early to mid-March. Consequently, the MOE drew up a set of guidelines and protocols that both students and teachers were required to follow in order to limit transmission and allow classes to continue safely and with minimal risk. Everybody had to wear a facemask and the students had to be seated socially distanced, separated by at least one empty desk and close social interaction was strongly discouraged which drastically limited the types of activities that could be done. Furthermore, those who had COVID like symptoms were allowed time off from classes to take a test and wait for the results. Anyone who tested positive was required to stay at home for 7 days before being able to return.

These guidelines have significantly impacted lessons taught across all disciplines with teachers and students having to adapt to new classroom dynamics and interactions. However, it is logical to suggest that English as a foreign language (EFL) classes, which are commonplace in the Korean university curricula, will have experienced greater than average disruption as a result. It is widely accepted that an effective EFL class will include inter-learner communication in group or pair work (Richards & Rodgers, 2001; Brown, 2001) and also needs clear and concise communication between the students and the teacher (Swain, 2005; Ellis, 2008). Furthermore, previous research (Fay, Aguirre, & Gash, 2013; Hamamc─▒ & Hamamc─▒, 2017) has shown there is a relationship between consistent student attendance and language learning performance. Clearly, having to wear a facemask, the restrictions on student interaction, and mandatory absences as a result of having to take a test and/or positive result is going to severely affect how both teachers and learners approach the post COVID EFL classroom.

As discussed by the United Nations (2020), an essential task as part of the road out of the pandemic is to ensure teachers have the pedagogical skills and ability to adapt to different learning strategies. Therefore, given this type of classroom will be an unfamiliar educational environment, this study was designed to examine how EFL teachers at Korean universities felt post COVID regulations affected their classes and what approaches they took to try and overcome these challenges.

Beginning in the 1970РђЎs, the communicative approach to language instruction became increasingly more prominent. Known as Communicative Language Teaching (CLT), it is a method which places greater emphasis on communicative ability and relies more on interaction through the use of group/pair work as a way of improving language skills (Desai, 2015). This inter-learner collaboration can arguably aid them in a number of different ways including: learning from listening to other students, producing a greater amount of language than during a teacher-led activity, increasing motivation, and improving fluency skills (Richards, 2006). CLT became the standard way of approaching EFL and as discussed in Jeon (2009), English classrooms in Korea which were heavily reliant on teacher centered classrooms have made the move to a more collective, communicative one.

In addition to more student-centered classrooms, CLT meant EFL teachers had to adapt and perform different duties in order to fulfill the needs of learners (Phoung & Vang, 2019). Since the introduction of CLT, there have been a number of suggestions on how to describe this new role. Breen and Candlin (1980) suggested that an EFL teacher should be considered as having two main functions. Firstly, as the one who expedites the communicative process in the classroom, and secondly as a supplementary participant in learning. Brown (2001) expanded on this by suggesting the teacher actually has four duties. The first of these is a facilitator to help learners set goals and objectives, provide learning materials, and evaluate progress. Secondly, they will assume the position of needs analyst by responding to learning requirements and preparing future lessons accordingly. Thirdly, they will act as a councilor by demonstrating effective communication by using paraphrasing, confirmation and feedback. Finally, as a group process manager, they will monitor and encourage learners without intentionally filling in any gaps in grammar or lexis (Littlewood, 2011). Instead, they should be noted and used to provide comments or further practice at a later date.

Undoubtedly, the COVID restrictions described above will have greatly affected how the principles of CLT could be effectively applied in the current EFL classroom. Inability to work closely in pairs or groups negates learning via student interaction which in theory is going to limit the options available to teachers in the classroom. Furthermore, impeded communication due to face coverings could lead to lack of understanding on the part of both students and teachers which is ultimately going to restrict the roles an EFL teacher can assume.

Being back in the classroom with COVID restrictions in place is seen as a relatively uncharted territory. With the gradual return to normality, research in this area has only recently become relevant. Outside of the field of education, a number of studies have looked at the general impact of COVID guidelines. Research done in the United Kingdom (Saunders et al., 2020), involving a survey and open-ended questions, reported on the impact of face coverings on hearing and communication. The majority of the 460 participants stated face coverings had negatively affected all aspects of communication and understanding. Face coverings made hearing difficult, but also left people feeling embarrassed and frustrated due to increased anxiety and stress with people losing their willingness to engage in conversations. In a German study (Truong et al., 2021) with native listeners and speakers it demonstrated wearing masks proved problematic. This study showed listeners produced less speech and fewer words when asked to recall sentences from a masked speaker than an unmasked speaker, suggesting face coverings offer fewer cognitive resources to reproduce speech as they conceal visual speech information which degrades the acoustic signal. A different investigation (Marler & Ditton, 2020) in the field of healthcare noted wearing masks jeopardizes the ability of staff to successfully communicate with colleagues and patients which limits efficiency and effectiveness of treatment.

More specific to education, Spitzer (2020) concluded wearing masks greatly inhibits how to communicate, interpret, and mimic the expressions of those we are conversing with. The study also confirmed positive emotions become less recognizable and negative emotions are amplified due to masks covering the lower half of the face, which reduce not only the bonding between teachers and students, but also group cohesion and learning. A case study from Turkey (G├╝ne┼Ъ, 2021) examined several articles from different countries on the effects on masked education for students when learning a language. This research proved wearing masks had affected students in several ways, not just from verbal communication but also from facial expressions, nonverbal communication and language skills development. The findings from this case study showed students all suffered from hearing problems, understanding pronunciation, and speaking clearly. In addition, they were not able to see facial expressions which contributed to their lack of language skills development. Further to this, a study (Bauza Mas, 2021) from an EFL class at a secondary school in Spain also demonstrated wearing a mask severely affects the auditory and articulatory perception and pronunciation in a negative way. In contrast, an alternative study by Roy (2020) argues that Рђюmasks may have a potentially positive academic, emotional and self-awareness developmental impact on students.РђЮ (p. 710). In terms of masks being worn by teachers, there appears to be a shortage of data; however, one study by Lee (2021) discussed how face coverings worn by a teacher has the potential to affect voice volume, non-verbal communication, and can also lead to comfort issues when worn for long periods.

In addition to the issues caused by mask wearing, social distancing guidelines also have the potential to disrupt the CLT EFL classrooms. With students and children socially separated, it goes against the natural urge for them to get close and socialize, which in turn could lead to isolation and loneliness. The longer this continues, the higher the risk for feelings of anxiety, stress and depression could occur (Life, 2020). Furthermore, Richards (2006) argues that student performance and attainment can be affected by up to 50% in classrooms with less-than-ideal seating arrangements, and further studies (Byers et al., 2018; Wentzel, 2009) demonstrate the physical environment of a classroom significantly impacts student comfort, classroom behavior and peer interaction. One solution to this could be innovative uses of technologies; students and teachers can work together to create engaging environments that allow students to share ideas and collaborate (Martonrini, 2020). However, this is still going to limit the amount of face-to-face interaction possible and one study from Australia (Kite, et al, 2020) and another completed in Korea (Richards & Jones, 2021), has shown university EFL learners are often reluctant to engage with others within online collaborative tools such as discussion boards.

One more noticeable factor that could impact teaching and learning this semester compared to pre COVID classes, was the number of student absences. Those taking a test were granted 2 days of excused absence until the result was confirmed and those testing positive had to stay at home for 7 days. Consequently, there was a considerable increase in student absences during the spring semester of 2022 semester with five times as many students being absent compared to the pre-COVID semester in the winter of 2019. Several studies (Malcolm et al., 2003; Jing et al., 2021) have noted prolonged student absences not only significantly impact student progress but also increases the amount of work for teachers.

Despite previous research conducted in this field, there appears to be a lack of data which relates to EFL classes, particularly in the South Korean context and there is no clear information on when COVID restrictions will be lifted completely. At the time of writing, the social distancing protocol has been removed; however, the mask mandate and enforced absence rules are still in place. With new COVID infections doubling from just under 10,000 to just under 20,000 in the space of two days as a result of the high contagious BA.5 variant (Kim, 2022) there is every possibility of classes in future semesters being affected by these regulations. In order to ensure the quality and effectiveness of future EFL classes at Korean universities, it is important to understand their pedagogical impact and what teachers are using to try and overcome them. Therefore, this study will attempt to add to the current pool of data in this field by answering the following research questions:

The data for this study was collected between May 12th, 2022 and July 5th, 2022 from colleagues of the authors working in the same department at a university in the greater Seoul area who were asked to voluntarily participate. In total, 17 people completed a survey, 9 (52.9%) were female and 8 (47.1%) were male. In terms of the participantsРђЎ age, 2 (11.8%) were between 31 and 35 years old, 3 (17.6%) between 36 and 40, 6 (35.3%) between 41 and 45, 4 (23.5%) between 46 and 50, and the remaining 2 (11.8%) were aged in the 51 to 55 bracket. The vast majority (70.6%) were from Korea with the rest originating from either Great Britain (11.8%), Canada (11.8%), or the USA (5.9%). Ten out of the 17 respondents (58.8%) have been working as English teachers at a Korean university for between 11 and 15 years, 6 (35.3%) for between 6 and 10 years, and 1 (5.9%) for between 1 and 5 years. They indicated they were responsible for teaching classes with a range of primary focus. All of the respondents (100%) had at least one writing based course, 9 (52.9%) also said they had a class based on improved presentation skills, 3 (17.6%) had a speaking class, 2 (11.8%) had a reading-based class, 1 had a listening class and РђўotherРђЎ was selected once.

Study data was collected using two different methods. Initially, a Google Form was used to create a survey questionnaire (Appendix A) in early May, 2022. This method of data collection was chosen for a number of reasons which were outlined in (Evans & Mather, 2005). It added flexibility to the project and allowed data collection without any space and time constraints, it also allowed the use of several different question types to get a broad range of answers, and helped with collecting a large sample of data. In addition, since a survey questionnaire is one of the most effective ways to establish perceptions towards certain topics or situations (Young, 2016), the research team decided it would be a suitable data collection method for this project. Prior to the main data collection, the survey was shared with 4 colleagues of the research team who were independent of this project. Their feedback was used to establish validity prior to its distribution via a link which was sent by email. There were 18 questions in total with the first 3 related to demographic information and the following 2 focusing on teaching experience and current teaching context. The remaining questions were a combination of short answer questions, multiple choice, and 10-point Likert scale questions which the research team felt would reveal a wider spectrum of data than a 5-point scale. It was not possible to run a reliability test for every survey item, but a Cronbach Alpha test produced a score of 0.73 indicating good internal consistency. A Yes/No question at the end of the survey was used to gain permission from each participant to use the data as part of this study.

At the end of the data collection period, the automated collation option in Google forms was used to create an Excel spreadsheet for analysis. The final question of the survey asked participants if they would be willing to be contacted to discuss some of their responses in more detail. Those who agreed were asked to leave their email address. During the data analysis phase of this study, any survey responses thought pertinent were explored and discussed via email / online video call.

The concluding section of the survey offered the participants a small token of appreciation for their time in submitting their thoughts. A high number of short answer questions meant completing it could have been quite time consuming; hence, a coffee coupon to the value of 5000 Korean won was provided to those who indicated their interest. 4 out of the 17 respondents did so and left either a phone number or e-mail address to which the coupon could be electronically sent.

As part of the data analysis process, the two researchers arranged and explicated the various responses from the survey participants to a Likert scale and multiple-choice questions and analyzed them using descriptive statistics. Regarding the open-ended questions which gave a more in-depth insight to the participantsРђЎ views, the researchers applied a general analysis of qualitative research. Initially, they individually examined the data, noting common trends. Following this, the researchers met several times to compare notes and share ideas to establish patterns and themes. During these meetings, discussions were held to finalize the overall results and clarify any inconsistencies.

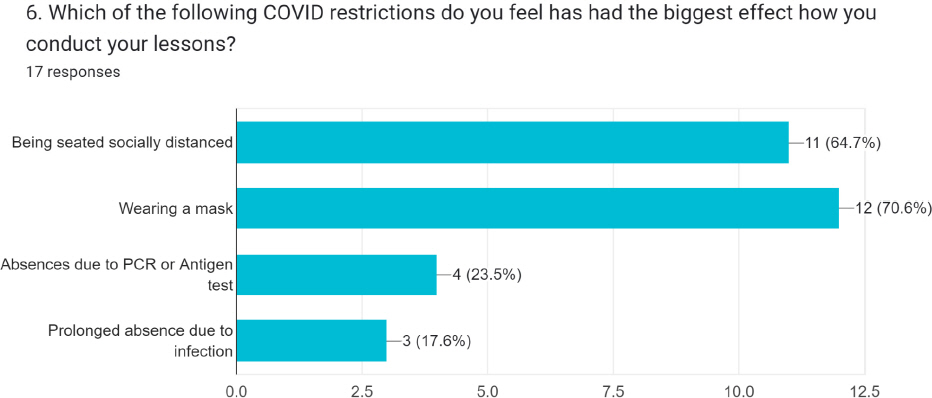

The initial research question in this study was to determine which of the MOE imposed restrictions teachers thought had the biggest impact on their classes. As can be seen in the data from question 6 (Figure 1) The participants reported wearing masks had the greatest effect with 12 out of 17 (70.6%) them selecting it. Following this, 11 out of 17 (64.7%) respondents noted social distancing affected the way classes were conducted with students being seated separately from each other. Unsurprisingly, only 4 out of 17 (23.5%) and 3 out of 17 (17.6%) participants stated that students being absent for a PCR or antigen test and prolonged absence due to infection affected how they conducted their classes, respectively. This shows that absences in a class rarely affect how teachers approach their class.

Similarly, question 7 asked the participants which COVID restrictions they felt had the biggest effect on classroom communication. Somewhat expectedly, wearing masks was chosen the most often, with 15 (88.2%) selecting it. This fits with previously mentioned research (Spitzer, 2020; Truong et al., 2021) showing masks proved problematic including hearing difficulties, producing less speech, understanding language and inhibiting communication. Being seated socially distanced was also viewed as having significant effect as 8 out of 17 (47.1%) chose this option.

Survey question 8 asked the respondents which COVID restrictions affected student learning the most. Almost everyone, 15 out of 17 (88.2%), indicated being seated socially distanced had the biggest impact. One possible reason for this is they view this restriction as inhibiting their ability to implement a CLT approach in which student collaboration helps produce more language, increases motivation and improves fluency (Richards, 2006). 9 out 17 (52.9%) participants also mentioned students being absent for prolonged periods due to infection and 6 out 17 (35.5%) noted being absent for a PCR or antigen test affected student learning. A number of participants said class materials were uploaded to the university learning management system (LMS) each week in order to help those who were absent to keep up with course content. Despite this, they still seemed to feel this was not enough to substitute for class attendance. Surprisingly, only 5 participants (29.4%) felt wearing a mask affected student learning although there were no clear reasons for this.

It is clear the social distancing and masks mandates were having the biggest effect on classes; consequently, a more in-depth analysis of the results and detailed discussion of them is included below.

In order to interpret in more detail how their classes were affected, the participants were asked 7 questions (survey questions 9-16) which were included to develop a better understanding of how each specific restriction influenced their lessons.

In terms of the students being seated socially distanced, there were several clear themes apparent in the data. The most frequently mentioned of which is the lack of pair work/group work being possible. There appears to be a feeling of frustration that this option was not available to teachers and the only approach left was to operate lecture style lessons with little interaction. Comments left in response to survey question 9 stated, РђюNot many choices for doing a class. I just lectured instead of doing any group work.РђЮ Another participant added, РђюHad no choice but to stand at the front and lectureРђд.having so few options was very frustrating.РђЮ This sentiment was echoed in several other responses and was followed up via email in which a different respondent commented:

After having classes online for the past 2 years, I was looking forward to some face-to-face interaction in classes this semester. However, I quickly realized this was not going to happen, which was the biggest disappointment of this semester. In the first class students sat alone, and it felt like a lecture. I couldnРђЎt tell them to change because of the restrictions. I was hesitant to do group work or activities in my classes. I really wanted to but I was worried the students might be reluctant.

In addition to this, socially distanced classes appear to have altered the pedagogical approach in the classroom. There is a clear indication teachers began to rely on PowerPoint a lot more as a medium of sharing information and content in the classroom. One comment left on the survey which was mirrored in a number of other responses stated, РђюBecause the situation has limited the types of interaction in classroom activities. I have prepared and offered more PPT slides for the students.РђЮ Interestingly, this change is something many seem unhappy about: РђюLess group work, a lot more ppt, which is not great.РђЮ A different participant added, РђюLess group work, more use of ppt, less class handouts, more teacher talk which is not a fun combination.РђЮ

The final effect of being seated apart relates to the teacherРђЎs enjoyment. Several participants mentioned they felt the restrictions had taken the fun out of their classes and were not as enjoyable as they have been in the past: РђюClasses were not as fun or energetic and students didnРђЎt engage with each other.РђЮ; Рђюvery boring, no group work.РђЮ.

Ultimately, these changes appear to have had one clear effect on the classroom environment and atmosphere, which is that lessons are a lot more boring. Responses to survey question 10 show a clear trend of classrooms being cold and sterile as a result of reduced interaction: РђюAll classes are very very cold. I think the students did not feel any connection to each other and me.РђЮ wrote one participant. Рђюboring, cold, not funРђд.it seems that class has become plain and less interesting.РђЮ wrote another. When contacted to discuss this in more detail, one participant elaborated:

Classes feel very boringРђдit feels like a lecture, only one communication from teacher to student. no interaction between students. I have been trying to find ways to make the class more interesting but it was not easy.

Overall, this data supplements the arguments put forward by studies reviewed earlier (Richards, 2006; Byers, Mahat, Liu, Knock, & Imms, 2018; Wentzel, 2009) Surprisingly, 2 of the respondents indicated they felt social distancing had no significant effect with one comment stating, РђюThe seating arrangements for writing classes has not affected the way I conduct my classes.РђЮ There was no clear explanation for this comment; however, since this was related to a writing course, that teacher may view the CLT approach as not being as important as it could be for teaching other skills, such as speaking.

In terms of wearing masks in the classroom, there were several clear implications apparent in the data. The first one relates to teacher student communication. When asked how the students wearing a mask has affected how they conduct a class (survey question 11), there was an indisputable feeling that wearing masks causes breakdowns in communication and consequently leads to increased reticence and reduced willingness to volunteer answers or be involved in any in-class discussion. More than half of the respondents said initial difficulty in hearing due to face coverings lead to the need for the teacher to ask for repetition or for the student to clarify what they meant. This caused students to believe they had said the wrong thing which led to embarrassment. This idea can be seen in a number of comments left on the survey which have be summarized in Table 1.

Collection of responses to survey question 11

When asked about this in a follow up email, one participant commented:

Due to the masks, I find that it takes longer to communicate with one another. Sometimes, when I ask students to repeat themselves their voices get even softer or mumble. I get the feeling that they do this because they thought they said the wrong answer. I end up telling them that I just couldnРђЎt hear them because the masks are blocking their voices. On top of that, I have some hearing loss, which makes it more difficult. When students do speak up voluntarily, sometimes it is hard to locate the sound and identify who said what. Overall, I feel that these types of situations lower their confidence when it comes to speaking English.

Furthermore, if a situation like this occurred, it appears the teacher felt like it not only affected a single student, but also was noticed by the whole class which led to other class members being reluctant to provide any oral responses to teacher prompts. One survey comment stated, РђюOften causes misunderstandings, hard to hear answers, students get embarrassed and are then reluctant to offer answers in the futureРђдknock on effect, other students see this and then they donРђЎt volunteer.РђЮ

In addition to masks making it hard to hear, the fact they cover a large proportion of a personРђЎs face also appears to affect teachersРђЎ ability to check for comprehension and understanding. Only being able to see a studentРђЎs eyes above the mask does not allow the teacher to see any other expressions that could indicate whether they have understood either course related content or instructions from the teacher. A selection of comments related to this which were echoed by several other participants can be seen in Table 2.

Further comments on how mask affected classes

These findings seem to mirror those mentioned in several of the studies discussed in the literature review (G├╝ne┼Ъ, 2021; Bauza Mas, 2021) but interestingly are opposite to those found by Roy (2020).

One further implication of wearing a mask relates to how effectively teachers feel they can deliver class content (survey question 12). Many of the respondents felt it caused them to change either the volume of their voice and/or how many times they would repeat instructions in the class: РђюI think I spoke louder and also felt I was repeating myself more because I was not sure If students had understood.РђЮ Another participant stated, РђюIРђЎm worried students might not understand me. I feel like I repeat myself very often and maybe speak louder because of the mask.РђЮ. When asked to elaborate on this in a personal correspondence, one participant said:

Luckily, I have a loud voice. However, facial expressions are important when it comes to communication, especially when speaking to non- native English speakers. Sometimes I tell a joke and am smiling underneath my mask, but because they canРђЎt see that I feel I may have confused them and then end up explaining myself just in case.

Finally, several participants suggested wearing masks resulted in some personal discomfort while teaching which first and foremost could have a detrimental impact on their physical wellbeing. РђюI was sometimes short of breath when talking to class.РђЮ asked one participant. РђюI felt stuffy and hot, breathing was hard and I had to speak a lot louder - I even used the class microphone for the first time this semester.РђЮ added another. Furthermore, they cause discomfort which limits their effectiveness as a teacher: РђюI think wearing a mask myself also gives the same kind of impression or effect on students. It seems less effective to deliver content or messages and manage the class.РђЮ A different participant said, РђюThink my voice is louder now. Also, I always found myself having to readjust the mask which interrupted me.РђЮ. Generally, these findings correlate with those discussed by Lee (2021).

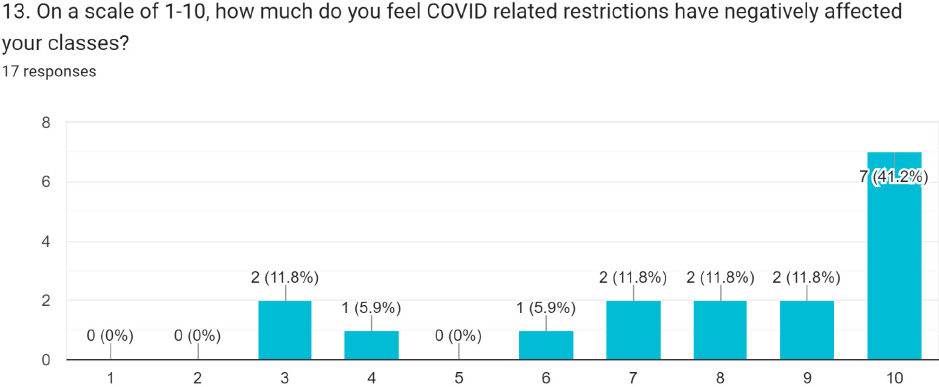

Overall, as can be seen from the results of survey question 13 (Figure 2), there is general feeling COVID restrictions had a negative effect on how classes were conducted with 41.2 % answering 10 and 64.8% selecting 7 or higher. However, with approximately 35% selecting 6 or lower it is slightly surprising more participants did not indicate the restrictions had a more severe effect.

This appears to show that despite some inconveniences caused by the restrictions, in general teachers were able to conduct their classes as normally as possible. However, the results of survey question 15 (Figure 3) show they felt student engagement with the teacher, peers and course material was severely affected with over 80% selecting 3 or less when asked if they found students to be more or less engaged when compared to pre-COVID class. This was elaborated in the responses to survey question 16 and has the potential to severely affect student learning and achievement:

No connection with each other. I often find students develop friendships with people they sit next to in normal class. They can interact and talk about the class together which helps with class engagementРђдsimilar thing with being able to do group work.

No communication between studentsРђд.at first, I thought they didnРђЎt know each other but it turned out from seeing them during breaks that a lot of them were already friends, they just seemed the restrictions in class made them act like strangers to each otherРђдmade the class very cold

Being seated apart and not being able to do group/pair work meant very little inter-learner interaction. One student told me because OT was canceled because of COVID, the students did not really know each other well which meant they were even more reluctant to engage with each other.

Research question three attempted to provide insight on how participants tried to overcome these challenges. The most prominent data point from the responses to survey question 17, is that participants tried to incorporate a variety of different technological uses into the classroom. One replied by saying, РђюI used programs and websites on the internet they could use on their phones. Like Kahoot and the schoolsРђЎ LMS.РђЮ Another mentioned, РђюI supplemented with more materials - I tried to bring in extra fun activities and used the internet for clips and quizzes in classРђЮ

However, there was an underlying theme to these responses, noting technology was used in the classroom but with limited success. One participant stated, РђюI tried to use discussions and peer feedback on e-learning but it didnРђЎt work well. Students were not interested in communicating with each other.РђЮ Another participant added, РђюTried e-learning, online, Kakao chatting room for the classРђд. very little engagement from the students. I tried group /pair work editing on canvas, but it did not work very well. Hardly any students tried and those who did not seem to enjoy it.РђЮ Further to this, another participant responded:

I tried using e-learning to foster discussions. DidnРђЎt workРђдnobody seemed to volunteer, tried google docs to collaborate on screen in the class. Worked okРђдbut with a lot of technical problems, tried KahootРђд.worked well but gets boring quickly and needs to be used sparingly.

Moreover, one participant mentioned they tried to use different technologies to help overcome the restrictions; however, it did not compare to a pre COVID classroom environment, stating, РђюI tried using e-learning for group work, tried using interactive tools like KahootРђдI donРђЎt think any of them were that successful. I donРђЎt think there is any substitute for having normal classes.РђЮ Table 3 shows all the different technologies that were used to help overcome COVID restrictions, albeit with limited success.

Most common types of technology used

Overall, it seemed there was limited success by incorporating technology in the classroom to overcome the restrictions, there is little evidence as to why from this data. However, these findings correspond with previously mentioned studies (Richards & Jones, 2021; Kite, et.al., 2020) Even though students are sat socially distant from one another and they had to wear masks, this should not have an effect on why using technology didnРђЎt help in the classroom, as most of the tasks were individually completed. Possible further research can be taken to look into this in more depth.

A second feature participants mentioned is the need to encourage the students in class. One participant revealed, РђюI tried to encourage students to participate in classroom activities.РђЮ Another participant added, РђюI encouraged individual participation.РђЮ Participants may have sympathized with the students knowing how difficult the situation is with the class restrictions and gave some encouragement to help motivate the students. One participant followed up on this via email explaining how some students struggled to cope during these difficult times.

I have seen and heard stories of the mental health of my students this term. This was the first semester in my years of experience where at least 4 students reached out either in their assignments or in person to share their struggles with mental health issues. I had one student explain how he did not come to class last week as he tried to hang himself in the bathroom on campus. The bruises on his neck were clear; he tried his best. This triggered a message to all my students at the start of class that if they need help or someone to talk to, get it. If IРђЎm that person then I will do my best to listen. But in the meantime, be nice to your classmates as you never know what they are going through. Afterwards even more reached out to me to share their struggles.

Although this response was unrelated to how to overcome COVID restrictions in the classroom, it highlights the need for mental health awareness and education as discussed earlier by Life (2020). Once more, this could be an interesting research topic for the future.

In addition to overcoming the challenges, survey question 18 asked if there were any positive outcomes of teaching classes during COVID related restrictions with the majority indicating there were not that many. Several of these responses can be seen in Table 4.

Summary of comments about the return to the classroom

Adding to this, one participant noted how limited the activities were by replying, РђюThink I have learned how important having freedom is in the classroom by using a variety of teaching techniques.РђЮ Although not specifically mentioned in the comments, it proves that the participants preferred the freedom of a pre-COVID pandemic classroom, whereby the teaching method would have been predominantly a CLT style, which is in line with previously mentioned studies (Desai, 2015, Richards, 2006).

This research was carried out under the unique circumstances of being back in the classroom for the first time since the pandemic began. While there have been previous studies on certain aspects of these restrictions, especially wearing face coverings, very few, if any, have focused on teachersРђЎ perspectives of returning to the classroom under these conditions. From the research findings there are several important implications.

Firstly, it is clear that there are limited positive outcomes with being back in the classroom under COVID restrictions. The mask mandate hugely impeded all forms of communication and interaction between both teachers and students. One possible repercussion from this could be the implementation of mandatory transparent masks in the classroom as research has shown facial expressions and movements aid communication and language development (G├╝ne┼Ъ, 2021, Spitzerm, 2020).

Secondly, as students were socially distant from each other and the university limited pair/group work, teachers had to deliver the class content in a somewhat unconventional way. Before the pandemic started, teachers were used to a more dynamic and active learning environment as classes were delivered in the CLT method in which student collaboration produces more language and improves fluency skills and increases motivation (Richards, 2006). However, in the post-COVID classroom, teachers felt the classes were monotonous, unstimulating, and simply put, not as active and fun as they could have been. If these restrictions continue in the long term, then there could be a need for not just teachers, but also the university administrations to explore how the benefits of CLT can be maintained in socially distanced, mask mandated classrooms.

Furthermore, this study has once again highlighted the reluctance of EFL students in Korea to engage with online interactive learning tools. This has been mentioned in a number of previous studies and it is clearly a continuing trend. The reasons for this are not clear, but further research to understand why could lead to improved inter-learner communication in classrooms with COVID related restrictions.

A somewhat unexpected implication that was brought about by this study was that teachers noticed the mental health situation of some students. As mentioned in a study (Life, 2020), students that are socially separated may feel isolated and lonely. The longer this continues, the higher the risk for feelings of anxiety, stress and depression could occur. From this, the university must educate the students and make them aware of mental health issues and provide a platform for help if needed.

Ultimately, if the advantages of returning to the classroom do not outweigh the disadvantages, and if the MOE implements these restrictions for the foreseeable future, is there a need to really be back in the classroom? Or should classes be online until all restrictions are dropped until we can return to a classroom that is dynamic and engaging for both teachers and students?

While the findings of this research have disclosed some possible implications concerning the challenges faced with COVID restrictions in the classroom and how to overcome them, the researchers are aware of several limitations to this study. Although attempts were made to collect as much data as possible, the research was conducted at only one university with a relatively low number of participants. 17 respondents to the survey questionnaire are not enough to provide an adequate amount of data from the target population.

Secondly, the research findings were retrieved from a selection of multiple choice or short answer survey questions. Even though some respondents emailed with longer detailed answers, a more in-depth qualitative perspective including interviews and discussion groups would be needed to uncover further possible findings.

Finally, most of the data collected were from participants who taught writing and presentation classes and it would be interesting to see if there would be any variation and outcomes in the data if the participants had taught in a variety of other English disciplines.

References

Bauz├АMas, P. (2021 РђюThe Impact of Masks in the Intelligibility of English as a Foreign LanguageРђЮ, UIB Ripostori, https://dspace.uib.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11201/155756/Bauza_Mas_Paula.pdf?sequence=1

Breen, M, Candlin, C(1980). РђюThe Essentials of a Communicative Curriculum Language TeachingРђЮ, Applied Linguistics 1(2), 89-112.

Brown, H. D(2001). Teaching By Principles:An Interactive Approach to Language Pedagogy, White Plains, NY: Addison Wesley Longman.

Byers, T, Mahat, M, Liu, K, Knock, A, Imms, W. (2018 Systematic Review of the Effects of Learning Environments on Student Learning Outcomes, Melbourne: University of Melbourne, LEaRN, http://www.iletc.com.au/publications/reports

Desai, A.A(2015). РђюCharacteristics and Principles of Communicative Language TeachingРђЮ, International Journal of Research in Humanities &Soc. Sciences 3(7), 48-50.

Ellis, R(2008). The Study of Second Language Acquisition, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Evans, J, Mathur, A(2005 РђюThe Value of Online SurveysРђЮ, Internet Research 15(2), 195-219. https://doi.org/10.1108/10662240510590360.

Fay, R.E, Aguirre, R.V, Gash, P.W(2013). РђюAbsenteeism and Language Learning:Does Missing Class Matter?РђЮ, Journal of Language Teaching and Research 4(6), 1184-1190.

G├╝ne┼Ъ, F(2021 РђюThe Effect of Masked Education on Language SkillsРђЮ, The Journal of Limitless Education and Research 6(3), 337-370. https://doi.org/10.29250/sead.9Рєђ8.

Hamamc─▒, Z, Hamamc─▒, E(2017). РђюClass Attendance and Student Performance in an EFL Context:Is There a Relationship?РђЮ, Journal of Educational and Instructional Studies in the World 7(2), 2146-7463.

Jeon, J(2009). РђюKey issues in applying the communicative approach in Korea:Follow up after 12 years of implementationРђЮ, English Teaching 64(4), 123-150.

Jing, L, Lee, M, Gershenson, S(2021 РђюThe Short- and Long-Run Impacts of Secondary School AbsencesРђЮ, Ed Working Paper, 19-125, Annenberg Institute at Brown University https://doi.org/10.26300/xg6s-z169.

Kite, J, Schlub, T. E, Zhang, Y, Choi, S, Craske, S, Dickson, M(2020 РђюExploring lecturer and student perceptions and use of a learning management system in a postgraduate public health environmentРђЮ, E-Learning and Digital Media 17(3), 183-198. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753020909217.

Littlewood, W(2011 РђюDeveloping a Context-Sensitive Pedagogy for Communication Oriented Language TeachingРђЮ, English Teaching 68(3), 3-25. journal.kate.or.kr/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/kate_68_3_1.pdf.

Malcolm, H, Wilson, V, Davidson, J, Kirk, S. (2003 Absence from School:A study of its Causes and Effects in seven LEAs, Scottish Department for Education and Skills, https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/РЄЈ/1/RR424.pdf

Marler, H, Ditton, A(2020). РђюI'm smiling back at youРђЮ:Exploring the Impact of Mask Wearing on Communication in HealthcareРђЮ, International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 56(1), 205-214.

Phuong, L.T.T, Vang, L.T.N(2019). РђюThe Teacher'Roles in Communicative Language Teaching Classrooms:A Case Study at Nong Lam University - Ho Chi Minh CityРђЮ, Hnue Journal of Science 64(12), 28-34.

Richards, A, Jones, S(2021 РђюKorean Student Perceptions of a CANVAS Based EFL Class During COVID-19:A Case StudyРђЮ, Korean Journal of General Education 15(6), 265-285. https://doi.org/10.46392/kjge.2021.15.6.265.

Richards, J.C(2006). Communicative Language Teaching Today, Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J.C, Rodgers, T. S(2001 Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching, Cambridge University Press https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667305.

Roy, D(2020 РђюMasks Method and Impact in the ClassroomРђЮ, Creative Education 11(5), 710-734. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2020.115052.

Saunders, G. H, Jackson, I. R, Visram, A. S(2020 РђюImpacts of face coverings on communication:An indirect impact of COVID-19 View supplementary material Impacts of face coverings on communication:An indirect impact of COVID-19РђЮ, International Journal of Audiology 61(5), 365-370. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2020.1851401.

Spitzer, M(2020 РђюMasked education?The benefits and burdens of wearing face masks in schools during the current Corona pandemicРђЮ, Trends in Neuroscience and Education 20:100138.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tine.2020.100138.

Swain, M(2005). РђюThe output hypothesis:Theory and researchРђЮ, Edited by Heinkel E, Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning, 471-483. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Truong, L. T, Beck, S. D, Weber, A(2021 РђюThe impact of face masks on the recall of spoken sentencesРђЮ, The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 149(1), 142-144. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0002951.

Wentzel, K. R(2009). РђюPeers and Academic Functioning at SchoolРђЮ, Edited by Rubin K. H, Bukowski W. M, Laursen B, Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups, 531-547. New York: The Guilford.

Young, T. J(2016). РђюQuestionnaires and SurveysРђЮ, Edited by Zhu Hua, Research Methods in Intercultural Communication:A Practical Guide, 165-180. Oxford: Wiley.

<News Articles / Internet Sources>.

Jeong, A. (2021 РђюSouth Korea loosened covid rules after massive vaccine uptake. Now cases and hospitalizations are surgingРђЮ, Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/11/17/south-korea-covid-patients/

Kim, A. (2022 РђюBA.5 omicron poised to take over as dominant virus in KoreaРђЮ, Retrieved from https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20220706000651

Lee, C. (2021 РђюTeaching in Face Masks and Shields with Social Distancing - A Non-Scientific StudyРђЮ, Retrieved from https://www.gvsu.edu/cms4/asset/2C7E8377-04C3-04D0-D76E3802F3A13C9F/teaching_in_masks_and_shields_-_an_experiment.pdf

Life, J. (2020 РђюThe Impact of Social Distancing in SchoolsРђЮ, Retrieved from http://www.jaynelifetherapy.co.uk/blog/author/jayne-2/

Martorina, S. (2020 РђюSocial distancing in the classroom:how technology is aiding the new normal in higher educationРђЮ, Retrieved from https://www.fenews.co.uk/fe-voices/social-distancing-in-the-classroom-how-technology-is-aiding-the-new-normal-in-higher-education/

United Nations. (2020 РђюPolicy Brief:Education during COVID- 19 and beyondРђЮ, Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/08/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf

Appendix A

The purpose of this survey is to try and understand how COVID related restrictions such as social distancing and mask wearing affected the dynamics and efficacy of the post COVID EFL classroom at a university in Korea. Specifically, it will examine how instructors felt the restrictions affected their ability to teach, perceived student learning and also how they overcame these challenges. Your input is greatly appreciated. Should you have any questions related to this project, please contact one of the research team at stu11@hotmail.com or andyrichards@hotmail.com.

Demographic Information

Please answer the following questions about yourself.

1. Gender

2. Age

3. Nationality

Teaching Background and Experience

Please answer the following questions about your teaching experience.

4. How many years have you been working as an English teacher at a university in Korea?

5. What type of classes do you teach this semester? (Select all options that apply)

COVID Related Classroom Restrictions

The universitiesРђЎ return to the classroom guidelines at the beginning of 2022 spring semester stated:

All students must socially distance themselves from each other by sitting on separate desks or behind a protective screen.

Limit pair work or group work during class.

Masks are mandatory at all times while on campus.

Those who had to take a PCR test should stay at home until receiving test results.

Those who tested positive for COVID-19 should remain at home for 7 days.

6. Which of the following COVID restrictions do you feel has had the biggest effect how you conduct your lessons?

7. Which of the following COVID restrictions do you feel has had the biggest effect on student learning?

8. Which of the following COVID restrictions do you feel has had the biggest effect on classroom communication

9. In what ways have the students being seated socially distanced affected how you conduct a class?

10. How do you feel the lack of pair/group work activities affected your teaching/classes?

11. In what ways, if any, has the students wearing masks affected how you conduct a class?

12. In what ways, if any, has wearing a mask yourself, affected how you conducted a class?

13. On a scale of 1-10, how much do you feel COVID related restrictions have negatively affected your classes?

14. If so, could you explain how?

15. On a scale of 1-10, have you generally found the students to be more or less engaged compared to a pre-covid class

16. Could you specify in more detail how?

17. In what ways have you tried to overcome issues connected to COVID restrictions?

18. Have there been any positive outcomes of teaching classes during COVID related restrictions? If yes, please specify. Do you consent to your responses being used as data for this research project?

- TOOLS