|

|

- Search

| Korean J General Edu > Volume 17(5); 2023 > Article |

|

Abstract

In our increasingly interconnected contemporary society, the imperative of nurturing global citizenship and competence is evident when it comes to addressing the multifaceted challenges stemming from globalization. This study explores strategies for bridging the gap between in-class and out-of-class learning while expanding the reach of global competence into out-of-class learning settings. Building upon the General English course model by Oh (2021), which focuses on fostering global citizenship and competence, this research investigates the feasibility of implementing a supportive Community of Practice (CoP) model tailored for out-of-class learning environments. This study specifically assesses the potential of an online CoP model as a platform for the continuous cultivation and application of global citizenship and competence. Employing a collaborative autoethnographic approach, the research delves into the experiences of five university-level English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners actively participating in this CoP. The research scrutinizes various dimensions of their engagement, encompassing their experiences within the CoP, prospective enhancements to the model, and the impact of digital tools on their learning journey, such as machine translation and ChatGPT on their learning journeys. The findings of this study illuminate the transformative effects of CoP activities on learners’ attitudes, learning strategies, and the development of global citizenship and competence. Furthermore, it underscores the pivotal role of learners proactively harnessing technology, such as the ones mentioned above, in advancing both their level of global citizenship and their language proficiency. Additionally, the research underscores learners’ comprehension of the rationale behind learning activities as a critical factor in fostering meaningful engagement. Ultimately, this research offers a blueprint for nurturing the essential skills and perspectives necessary for learners to evolve as engaged global citizens in an interconnected and interdependent world. It aligns with the imperative of fostering global competence in response to the pressing demands of our globalized era.

Abstract

점점 더 긴밀하게 상호 연결된 현대 사회에서, 세계화로 인해 발생하는 복잡한 이슈들에 대처하기 위해서는 글로벌 시민성 및 역량의 배양은 필수적이다. 이 연구는 교실내 학습과 교실외 학습을 연계하는 동시에, 글로벌 역량을 교실외 학습 환경으로 확장하는 방법을 모색한다. 글로벌 시민성 및 역량의 함양을 목표로 하는 교양영어 수업 모형(Oh, 2021)을 바탕으로, 교실외 학습환경에서 실행 가능한 지원적 실천 공동체(CoP) 모형을 연구한다. 이 연구는 특히 온라인 CoP 모델이 지속적인 글로벌 역량의 실행 및 적용을 위한 플랫폼으로서 기능할 수 있는지 그 잠재적 가능성을 조사한다. 협력적 자문화기술지 방법론을 활용하여, 이 연구는 CoP에 참여하는 다섯 명의 대학 EFL 학습자의 경험을 심층 분석한다. 연구 질문은 학생들의 CoP 경험, 모형 개선을 위한 잠재적 아이디어, 기계 번역기와 ChatGPT 등 디지털 도구가 학습 여정에 미치는 영향을 탐색한다. 연구 결과, CoP 활동은 학습자의 태도, 학습 전략, 세계시민성 및 역량의 배양에 있어 변혁적 영향을 끼친 것으로 조사되었다. 또한 세계시민성 및 언어 역량을 개발하는 데 있어, 학습자가 주체성을 발휘하여 주도적으로 기계번역기와 ChatGPT와 같은 테크놀로지를 활용하는 것이 중요한 것으로 분석되었다. 또한 학습 활동의 근거에 대한 학습자 자신의 이해가 의미 있는 학습몰입을 유도하는 핵심 요인으로 조사되었다. 궁극적으로 이 연구는 글로벌 역량 배양의 필요성에 부응하여 학습자가 상호 연결 및 의존된 세계에서 의미 있는 세계시민으로 성장 하기 위해 필요한 기술과 시각을 교실외 학습으로 구현할 수 있는 모형을 제공한다.

The rapid globalization and interconnectivity of our contemporary world have been significantly shaped by the ubiquity of the Internet and the prevalence of smartphones. These technologies have granted individuals unparalleled access to vast amounts of information and real-time news updates from across the globe. As a result, fostering global competence in students has become increasingly crucial. Global competence enables individuals to effectively navigate and critically analyze authentic online information, as well as communicate opinions and collaboratively search for solutions to urgent global challenges, thus empowering them to become responsible global citizens.

Recognizing the importance of equipping students with these skills, an English course model was developed for cultivating global citizenship and global competence. This comprehensive model, proposed by Oh(2021), was designed using the backward design approach suggested by McTighe and Wiggins(1999). To validate its effectiveness, the model was applied as a case study, as documented by Oh(2022) and Kim and Oh(in draft). Implemented within a Content Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) framework, the model focused on four specific objectives: understanding globalization and global citizenship, grasping the concept of global competence, developing technological proficiency, and enhancing English language skills. Technological proficiency, in this context, primarily referred to the effective use of Machine Translation (MT hereafter).

The studies’ outcomes revealed significant improvements in students’ global competence, as measured by the PISA global competence survey, and notable enhancements in students’ self-efficacy across the four language skills. The use of MT was identified as powerful affordance for integrating content and language learning for the students with limited proficiency (Kim & Oh, in draft; Oh, 2022). These findings highlight the efficacy of the English course model in cultivating global citizenship and global competence among students. Despite these positive outcomes, it is essential to recognize that the internalization of these skills requires continuous practice and application beyond formal education. Students need a supportive community of practice(CoP hereafter) to refine and apply their acquired competencies until they achieve comfort and independence in real-world contexts. Such a community serves as a bridge, connecting structured college curricula with the practical implementation of skills in authentic settings. Furthermore, in order for the model to function as a life-long learning platform, it is essential to integrate students’ perspectives, reflections, and suggestions into its design.

To address this need, the present research aims to explore an online CoP model in an out-of-class learning context. This model is to be designed as a nurturing environment for ongoing practice and application of global competence, facilitating students’ seamless transition of learned skills into real-world scenarios. To investigate this agenda, a collaborative autoethnography approach was integrated into the research design. The first author served as the principal investigator, the second author provided guidance on the qualitative methodology, and five student- investigators conducted collaborative autoethnographies by actively participating in the online CoP for global competence and global citizenship. The study aims to address the following research questions:

RQ1. How do students experience the student-led online CoP model as a follow-up activity subsequent to completing a general English course?

RQ2. What insights and suggestions do they have for improving its effectiveness?

RQ3. Do Machine Translation and ChatGPT work as affordance in their learning in CoP? If so, how do they work as affordance?

By addressing these questions, this research contributes to the ongoing efforts to nurture global competence in students, thereby preparing them to effectively engage with the complexities of our interconnected world.

Educational objectives, in the form of constructs, require precise definitions to facilitate the development of focused pedagogical content, relevant activities, and reliable assessment tools with strong construct validity. This principle holds true when designing a course or program aimed at nurturing global competence. Given the diverse manifestations of global competence and global citizenship education across various contexts and disciplines (Lee, et al., 2017), it becomes essential to establish a clear definition of global competence specifically within the context of English as a foreign language education in a tertiary setting.

With the increasing enthusiasm and concerns surrounding the rapid pace of globalization and its diverse effects, various institutional actors have shown interest in addressing this agenda of globalization from their unique perspectives. According to Dill (2013), this agenda can be classified into two key facets: global consciousness and global competencies, each championed by different organizations with their respective discourses in the field. Dill explains that the discourse of global consciousness prioritizes ethical objectives, such as promoting tolerance, striving for world peace, and instilling high moral expectations in individuals to contribute to saving the world. Within this discourse, prominent institutional actors include UNESCO, the Ford Foundation, and the Global Issues Network (GIN). On the other hand, Dill elucidates that the discourse of global competencies places a stronger emphasis on equipping individuals with the skills and competencies required for success in the global economy. Organizations such as the OECD, politicians, governmental agencies, as well as funders like the Gates Foundation and the World Economic Forum actively promote this perspective.

The General English course model developed by Oh (2021, 2022) incorporates the definitions of global consciousness from UNESCO and global competence from the OECD’s PISA 2018 framework. UNESCO (2015) defines global citizenship as “a sense of belonging to a broader community and common humanity,” emphasizing the interdependency and interconnectedness between local, national, and global aspects. To cultivate students’ awareness as global citizens, the proposed model focuses on analyzing media articles related to five Global Citizenship Education (GCED, hereafter) themes: human rights, conflict and peace-building, respecting diversity, globalization and social justice, and sustainability. In contrast, the PISA framework defines global competence as a multifaceted construct that necessitates a combination of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values effectively applied to address global issues or intercultural situations (OECD). “Global issues refer to those that affect all people, and have deep implications for current and future generations. Intercultural situations refer to face-to-face, virtual or mediated encounters with people who are perceived to be from a different cultural background” (OECD, 2018).

In the general English course following the proposed model (Oh, 2021), students are encouraged to cultivate a sense of global citizenship through studying materials that highlight the interconnectedness and interdependence of the world, along with the complexities arising from these aspects. They also explore the concept of global citizenship itself and familiarize themselves with the five themes of GCED. With an overall understanding of global citizenship, students engage in reading media articles that address various global issues, such as the climate crisis, the implications of advanced AI technology, and conflicts like the Ukraine-Russia war. They approach these articles with a critical eye, analyzing the intricate issues and diverse perspectives involved. Additionally, students actively participate in discussions and reflection exercises to explore potential solutions and peace-building strategies as responsible global citizens. As of now, the model does not incorporate elements related to intercultural situations.

A crucial aspect of the model enabling learners with limited English proficiency to engage with authentic media articles is the integration of MT. Grounded in the theory of translanguaging, which claims deliberate engagement with learners’ entire linguistic and semiotic repertoires as valuable resources for learning, MT emerges as a powerful resource for crossing languages and for learning (Kim & Oh, in draft). The affordances of MT in this model were identified to be in the areas of reading and writing. To comprehend such articles primarily written for native speakers of English, a proficiency level of at least B2 in the CEFR framework is necessary, indicating the ability to grasp the main ideas of intricate texts covering both concrete and abstract topics, including technical discussions within their field of specialization (bit.ly/44C6HgW). Furthermore, students required the assistance of MT for writing summaries and formulating personal responses to those challenging texts. As per ETS, a B2 level corresponds to a minimum TOEIC reading section score of 385. Given this requirement, it seems necessary that the majority of students in a general English course should rely on MT mediation to access, comprehend, and write about authentic media articles.

As documented in several studies (Carré, et al., 2022; Jolley & Maimone, 2022; Klekovkina & Denié-Higney, 2022; Lee, 2021), the risk of over-reliance on MT is an important aspect that needs to be addressed when incorporating MT into the model. A crucial condition for MT to serve as a valuable resource is thoughtful and purposeful design, customizing its use to facilitate learning. In the domain of writing, Kim & Oh (in draft) demonstrated various ways to design the writing task so that MT could effectively support both content and language learning. This included conducting introductory lectures on MT usage, having students submit multiple versions of writing drafts using L1, L2, and MT, and providing teacher feedback.

To transform MT-mediated reading into effective language learning experiences, the model employs the think-aloud approach, which enhances learners’ linguistic and metacognitive responsiveness. Think-aloud, also referred to as protocol analysis, serves as a prominent research method in the field of reading for gaining insight into readers’ hidden cognitive processes while they are reading, enabling the collection of real-time information (Pressley & Afflerbach, 1995). In the proposed model, students are instructed to verbalize their thoughts while performing the MT-mediated L2 reading task, and they are required to record and submit a video of their reading process. Oh (2022) conducted a study on college students’ perceptions of using the MT-mediated think-aloud reading (TAR, hereafter) task and found several positive effects. These benefits include improved English proficiency, increased self-monitoring awareness, development of global competence, convenience, enhanced self-directed learning, and greater familiarity with English. By incorporating the think-aloud approach into MT-mediated reading, the model aims to ensure that learners engage with a given article not only for information acquisition but also for language acquisition. This approach consequently helps reduce reliance on MT and fosters more effective language learning experiences.

The model for the general English course on global citizenship and global competence (Oh, 2021) is built upon the concept of a “community of practice” derived from the situated learning theory proposed by Lave and Wenger (1991). The foundation of this model is the hypothetical establishment of a community of responsible global citizens. According to Wenger (1998), mutual engagement, a joint enterprise, and a shared repertoire are integral to creating community coherence, and the model attempts to realize these three essential dimensions of practice. Within this envisioned CoP, responsible global citizens are expected to actively participate; they collectively engage in global issues by negotiating meanings related to responsible global citizenship; they continuously create a joint enterprise of relations based on mutual accountability in the face of ongoing global challenges; these practices of MT-mediated media reading and writing are characterized by a shared repertoire among prospective global citizens.

The model envisions a general English course as a platform for enabling “legitimate peripheral participation,” which is a process of moving from the periphery to center, facilitating the integration of newcomers into a CoP (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 1998). Within this model, specific patterns of practice engaged by responsible global citizens are identified, such as maintaining interests in and updating information regarding ongoing global issues, forming and expressing critical opinions about them, and adopting a responsible attitude towards these issues. By incorporating opportunities to engage in these activities through the course, students are given “an approximation of full participation that gives exposure to actual practice” (Wenger, 1998, p.100) of responsible global citizens.

However, as mentioned earlier, internalizing the practices of responsible global citizens demands significant effort and a prolonged period of engagement. Merely experiencing actual practice several times is insufficient to fully incorporate it into one’s life, attitude, or way of thinking. Moreover, the dynamic nature of global issues constantly challenges global citizens to remain sensitive to emerging matters, necessitating continuous practice of global competence. Therefore, establishing a CoP in an out-of-class context becomes essential for the model to have a meaningful and lasting impact. The efficacy of Wenger’s Community of Practice (CoP) concept has been evidenced by its extensive use as a theoretical framework in studies exploring online and blended learning environments in diverse educational contexts and their impact on professional development (Jang, 2022; Kleinschmit et al., 2023; Smith, Hayes, & Shea, 2017).

In this qualitative study, we adopt an innovative meth- odological approach known as collaborative autoethnography (Chang, 2013) to explore the subjective experiences, perspectives, and reflections of the language learners themselves. An ethnography, the fundamental methodology in anthropology, is a study of people and cultures through prolonged engagement and participant observation to understand the culture and gain the members’ insider perspectives (Watson-Gegeo, 1988). An autoethnography uses the researcher’s personal experiences as primary data for the purpose of understanding social phenomena (Chang, 2013). The researcher being the research participant, autoethnography allows easy access to the participants’ emotions, motivations, and sense-making, offering unique contribution to the understanding of human experiences within a specific context (Chang, 2013). As such, it has become an increasingly popular methodology in the field of education, and naturally in second language education (Keles, 2022; Mynard, 2020).

In a collaborative autoethnography (Chang, 2013; Mynard, 2020), multiple researchers collaboratively investigate shared autoethnographic experiences. The degree of collaboration can vary, ranging from full to partial collaboration, throughout the stages of data collection, analysis, and the writing process (Chang, 2013). This collaborative approach addresses the limitations associated with single-authored autoethnography, particularly the issue of excessive researcher subjectivity when mixing the roles of researcher and participant (Chang, 2013). Despite the added complexity of managing and combining multiple narratives, we consider collaborative autoethnography as a promising methodology that offers rich insights into the language learning process from diverse learners’ perspectives.

The participants of this study, comprising the authors of this collaborative autoethnography, consist of five undergraduate students and two professors (first and second authors), both of whom teach the General English course based on the proposed model of this research. Such a co-authorship is relatively uncommon in the existing literature on autoethnography in second language education, which mostly involves researchers with PhDs writing about their own experiences of language learning/ teaching, teacher training, or research (Keles, 2022; Mynard, 2020). The specific authorship structure of this paper originated from the requirement of university funding for a partnership between professors and students as co-authors of a research paper. However, this approach aligns well with the objectives of this study, which involves transitioning a teacher-generated teaching model into an out-of-class, student-led, life-long CoP, fostering English and technological proficiency, and examining the role of MT and ChatGPT, which were crucial affordances for the students to become co-writers of this English research paper. This paper centers on the autoethnographies of the students as language learners, with the two professor-authors collaborating as the designer/teacher of the model and the principal investigator of the research (first author), as well as serving as the facilitator in guiding the students throughout the qualitative research process (second author).

The five student-authors voluntarily participated in this research project organized by the university, scheduled to take place during the summer break of 2023. All of them attended the General English course taught by the first author in the spring semester (March to June) of 2023. The General English course is mandatory for all incoming freshmen, who are placed into classes based on their TOEIC placement test results. These student- authors were part of the highest-level class, indicating their TOEIC scores were 500 or higher (Table 1). All five student-authors are females, with three pursuing a nursing major and two majoring in computer software engineering. They are granted authorship and received funding for their participation in the research project. Among the five students, Myeong and Jeon volunteered to assume the leadership role within the CoP, responsible for managing schedules and leading activities, and earned the position of the third and fourth author.

During the spring semester of 2023, all the students participated in the General English course, which was based on Oh (2021)’s model. Additionally, an out-of-class online CoP was established, where the first author developed a modified model. This model essentially follows a cycle of activities, including comprehension of a media article, analysis, writing of a personal response, and presentation, similar to the learning cycle experienced in the course. The skeleton of the activity flow is represented in Figure 1. Detailed instructions and posting guidelines for each step used in the CoP model at the initial implementation can be found in Appendix 1.

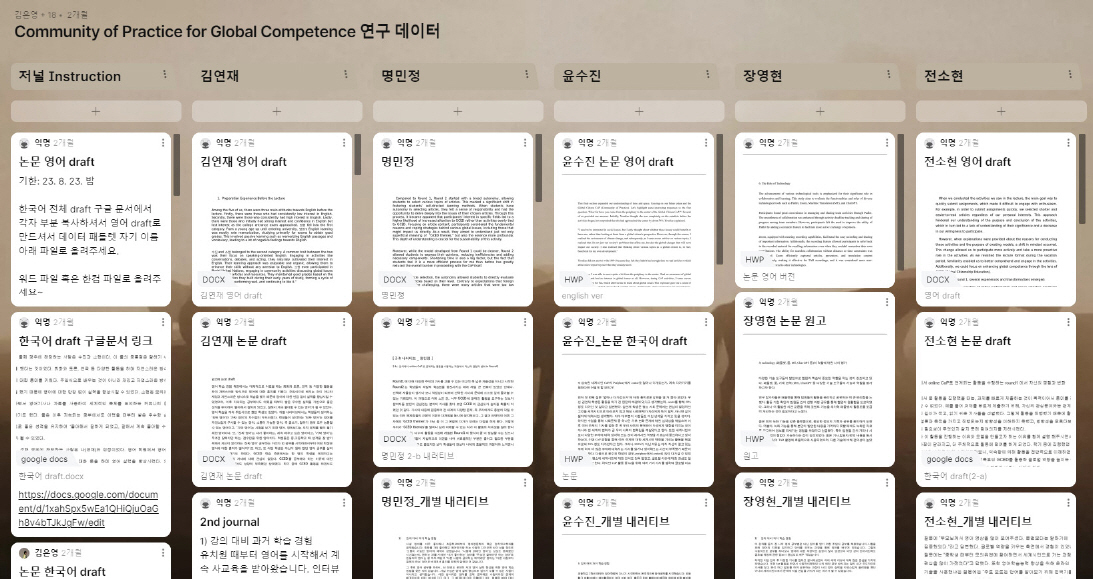

The autoethnographies within this study encompassed the comprehensive English learning experiences of the students, spanning from their early lives, through the General English course during the semester (March to mid-June), and culminated in the online Community of Practice (CoP) during the summer (from late June to late August). All interactions throughout this project took place via Zoom; there were no in-person meetings. Two Padlets were created: one for the CoP learning activities (referred to as the “activity padlet”) and another for collecting research data (referred to as the “research padlet”, as shown in Figure 2).

The project aimed to complete all work during the summer break, which led to tight schedules. Nonetheless, effective online interactions allowed us to accomplish our tasks. (The research procedure can be found in Table 2.)

Research Procedure

For the interviews and data analysis meeting, the second author utilized the autoethnographic interview method developed by Lee (2019), in which interviewees were asked to review their responses after the interview to extract deeper self-reflective narratives, making them active contributors to the narrative construction. This study employed a zoom-based autoethnographic interview method, in which the interview notes were shared on zoom screen and collaboratively analyzed. Specifically, the interviewee asked to read through the interview notes displayed on the screen, underline the sections they deemed important throughout the notes (the interviewer underlined the parts as told by the students), and explain their choices, which were immediately attached as memos by the interviewer. In group setting, this process was replicated for each individuals.

The student participants held dual roles, acting as learners within the CoP and as researchers of their own narratives. Even in their research role, the students were guided by the professors in conducting their research. After Round 2, the students assumed full research roles, composing their individual narratives. The narratives were organized into five sections: 1) English learning experience before the course, 2) Round 1, 3) Round 2, 4) technology, and 5) global citizen CoP. The detailed instructions can be found in Appendix 2. In the data analysis meeting, all authors collaboratively analyzed the five narratives using zoom-based autoethnographic interview method. Each student then assumed responsibility for one of the five sections and drafted a narrative integrating insights from all five individual narratives. Additionally, the second author contributed a section discussing the course. Myeong and Jeon wrote about the revised model.

In the Findings section below, we use the first-person perspective and our first names, following the conventions of autoethnography. Initially written in Korean, the drafts were reviewed by the professors and subsequently translated into English with the aid of ChatGPT.

This section presents seven narratives in response to three research questions, namely those related to student experience (RQ1), student insights and suggestions (RQ2), and the role of technology (RQ3). Each narrative is authored by one of the researchers as follows: 1) experience before the course (Yeonjae), 2) course experience (Eun- Yong), 3) Round 1 experience (So-Hyeon), 4) the revised model (MinJung & So-Hyeon), 5) Round 2 experience (MinJung), 6) the role of technology (Young-Hyeon), and 7) global citizenship CoP (Sujin). RQ1 is addressed throughout all the narratives, RQ2 is also covered across the narratives, with a stronger emphasis on the fourth narrative, and RQ3 is specifically explored in the sixth narrative.

Among the five of us, there were three main attitudes towards English before the course. Firstly, there were those who had consistently low interest in English. Secondly, there were those who consistently had high interest in English. Lastly, there were those who initially had strong interest and confidence in English but lost interest as the college entrance exam approached. Young- Hyeon fell into the first category. From a young age up until entering university, Young-Hyeon’s English learning was mostly rote memorization, studying primarily for exams to obtain good grades. This involved passive learning such as memorizing English passages and vocabulary, leading to a lot of negative feelings towards English.

Sujin and So-Hyeon belonged to the second category. A common trait between the two was their focus on speaking-oriented English. Engaging in activities like conversations, debates, and acting, they naturally cultivated their interest in English. Their learning approach was enjoyable and organic, allowing them to enhance their skills without any aversion to English. 소현 even participated in Model United Nations, engaging in community activities discussing global issues using English articles and resources. They maintained good grades based on the strong foundation they built during their early years of study, forming a cycle of “liking English, performing well, and continuing to like it.”

In the third category were me (Yeonjae) and MinJung. We improved our English skills by attending English academies, finding English articles, practicing composition, engaging in English debates, and conversing with native speakers. We had a genuine liking for English and possessed confidence in it. However, during middle and high school, we began to distance ourselves from studying what we considered “real English” as we prioritized obtaining good grades. This is where the distinction between “real English” and “test-oriented English” in our narrative became evident. “Real English” was about being able to use English naturally, for communication purposes, encompassing writing and speaking competencies. On the other hand, “test-oriented English” was focused on swift problem-solving for exams, emphasizing efficiency rather than a true passion for learning. While 민정 had a strong initial interest, it waned as she realized the need to engage in “test-oriented English” to achieve her dreams. She wrote:

Never have I once found a method of learning English that truly enhanced my language skills. I came to realize that the study techniques aimed at the college entrance exam were utterly unhelpful in the broader scope of my life. As someone who critically prioritizes efficiency in all forms of studying, the hours spent on English study were unbearably agonizing. I became weary of following the notion that interest leads to proficiency. I started actively avoiding English. I grew to genuinely despise it, and in essence, I haven’t engaged in English study since the latter half of my freshman year in high school. (Excerpt from MinJung’s individual narrative)

Studying for the college entrance exam simply involved familiarizing ourselves with the specific aspects that would lead to correct answers for each question type. It wasn’t about enhancing our English skills but adopting a strategy limited to the exam context. It wasn’t a method beneficial for life but rather for the test itself, and the notion that “liking English leads to proficiency and higher scores” didn’t hold true in this structure. Even students who initially enjoyed English faced situations where they began to dislike it due to this structure. This likely isn’t just the story of me(Yeonjae) and MinJung but might resonate with many students.

Regarding attitudes towards English and global competence, apart from So-Hyeon, we lacked interest in global citizenship education. Among the five students, three of us (So-Hyeon, Yeonjae, MinJung) had experienced activities related to Global Citizenship Education (GCED), including finding English articles of global issues, reading them, and preparing for discussion. However, we did not have mich understanding or motivation for studying GCED. MinJung encountered the concept of GCED for the first time in this course. Amidst immediate concerns, there was little room for interest in global issues extending beyond personal matters. So-Hyeon’s case was quite exceptional.

In terms of using translation tools, the students had considerable experience, although the recognition of their usefulness in English learning was limited. At the time before the lecture, ChatGPT hadn’t even been released, so experience with it was non-existent.

Through individual interviews with each student, I had the opportunity to capture the students’ perspectives on the general English course they undertook during the semester and, at the time, the upcoming online CoP process. Regarding the course, students generally found it to be beneficial for their English skills and expressed a positive evaluation on the exposure to global issues. They appreciated the chance to engage in discussions with their peers on various topics and spoke positively about their encounter with and utilization of ChatGPT.

However, there were differences among students in their level of interest in global competence at the end of the semester. Among the four students who initially had limited familiarity with global citizenship (Yeonjae, MinJung, Sujin, and Young-Hyeon), MinJung and Young- Hyeon, after completing the course, developed a deep appreciation for the opportunity to learn about global issues and cultivated a strong interest in global citizenship. In contrast, Yeonjae and Sujin did not notably develop an interest in global issues even after the semester.

Such difference was interesting. To highlight the positive transformations that occurred through the online CoP in the summer, which will be described below, we provide more detailed documentation of the negative comments here compared to the positive ones. Sujin explained that her lack of interest from the beginning prevented her from engaging in GCED activities. Yeonjae expressed:

Understanding and analyzing complex articles on global issues would undoubtedly be helpful. However, for the sole purpose of improving English skills, such intricate content might not be necessary… [Through English debates, essays, etc.], my English skills could have improved adequately without necessarily navigating the complexities of global issues. I’m not certain if we’re doing this because this paper is related to GCED, but as someone with no interest in GCED content, my enthusiasm for learning English seems to have waned. It would be more engaging to learn English by focusing on issues immediately around us. (Excerpt from Yeonjae’s individual interview notes)

For certain students, such as Sujin and Yeonjae, the course could not spark interest in global citizenship.

This seems to be related to the heavy coursework. All five students clearly articulated the heavy burden of assignments. They found the volume of assignments overwhelming, struggled to complete tasks due to a lack of understanding of their purposes and the connections between them, and often hastily submitted assignments without fully grasping their context.

All students mentioned that reading the introductory sections of this research paper written by the professors (Introduction, Theoretical Background, Methodology) and participating in the initial personal interview helped them gain a better grasp of the meaning and structure of each activity. They expressed regret that if they had realized this earlier in the course, their interest might have been more pronounced.

While the students were motivated to some extent by the research compensation for participating in this CoP, they also harbored expectations of becoming co-authors of the paper with the professors and having the opportunity to engage in group activities that integrated English and global competence. Sujin and So-Hyeon, who enjoyed English debates, and MinJung, who had previous experience with English debates and enjoyed group studying, expressed a desire to be part of such a community. However, they had reservations about finding peers who shared their interests. Sujin stated:

It would be great to have an English debate community with other classmates, but having an English teacher would also be fantastic. I enjoy relaxed conversations in English. However, I haven’t really come across any friends in university who share this interest. (Excerpt from Sujin’s individual interview notes)

Young-Hyeon, whose interest in global issues had grown, participated with a desire to revisit the activities from the course. In Yeonjae’s case, her perspective evolved during the personal interview. Initially, Yeonjae mentioned, “I think learning English individually is better. Unless it’s a conversation with a native speaker, coordinating schedules is cumbersome.” However, when the topic of the obligatory aspect of group participation arose, she quickly reconsidered her stance. She honestly expressed, “It does seem that when you do things alone, you don’t do as well. Having an obligation could be beneficial. I hadn’t thought about this aspect before.” This demonstrated how even long-held thoughts can change through small conversations. It once again highlighted the importance of community.

When we participated in the activities during the course, our main goal honestly was just to quickly finish our assignments, which made it difficult to be engaged in the course with enthusiasm. For example, in order to submit assignments quickly, we selected shorter and easier-to-read articles regardless of our personal interests. With such attitude, we could not understand the purpose or the endpoint of the activities, which in turn led to a lack of understanding of their significance and a decrease in our willingness to participate.

However, when explanations were provided about the reasons for conducting these activities and the purpose of creating the CoP model, a shift in mindset occurred. This change allowed us to participate more actively and take a more proactive role in the activities. Because we were repeating the course format, familiarity enabled us to better comprehend and engage in the activities. Additionally, we could focus on enhancing global competence through the lens of GCED.

Reflecting on Round 1, several experiences and transformations emerged:

Firstly, the incorporation of online participation and group activities positively impacted engagement. Even though we had experienced similar activities during the course, the mandatory nature of group work led to more disciplined submission within the specified timeframes. The online space, particularly through platforms like Padlet, facilitated interaction and enabled us to view and communicate about each other’s assignments. Observing other submissions provided direction for our own work, and seeing well-executed assignments motivated us to put in more effort. Moreover, this environment allowed us to acquire knowledge from other participants’ articles, beyond our own selection.

Secondly, the importance of prior experience became evident. Repeating the process of selecting articles for the activity and engaging in group presentations after the course gradually piqued our interest in GCED. This, in turn, enabled us to think more about the essence of being a true global citizen, leading to a deeper understanding of sentences and fostering proactive engagement in CoP activities compared to assignment-based tasks during the course. Also, repeated exposure to technologies like ChatGPT enhanced our comprehension of its usage. We particularly recognized the quality difference in answers between Korean and English queries. Prompts like “correct” and “elaborate” highlighted the significance of word choice. Through repetition, our focus shifted from seeing the activity as a method of learning English to valuing the benefits gained from it.

Thirdly, improvements in English proficiency and global competency emerged. In previous activities during the course, the purpose of the task and its relevance to English proficiency were not fully grasped. However, this CoP activity led to the enhancement of English skills for all participant. Taking ownership and actively participating compelled us to delve deeper into the selected articles. Consequently, our ability to interpret sentences improved, and expressing thoughts and insights during group presentations necessitated acquiring specialized vocabulary. Our proficiency in constructing sentences and vocabulary visibly improved. Personally selecting articles sometimes meant tackling challenging pieces, and this process showed how English articles could aid in language learning. Reading articles and analyzing them contributed to both language development and global competence. The accessible medium of “articles” facilitated easy acquisition of global perspectives and social knowledge.

Lastly, as we conclude the activity, there are aspects we would like to modify. In transitioning to the next model after Round 1 that would be sustainable for us, the emphasis on group activities could be heightened. Recognizing the importance of using English for increased interest and improved learning abilities, participants found value in expressing themselves through written and spoken English. The presentation during Round 1 reignited interest in English for some participants, and conversations revolving around personal thoughts and opinions added depth. To provide a visual summary of the discussion, Figure 3 displays a snapshot from the Zoom discussion activity video. Simplifying the activity by eliminating unnecessary parts and concentrating on more crucial aspects was another consideration. By streamlining processes like the activity of previewing and reducing word counts, the sustainability of the model could be boosted.

Following the conclusion of Round 1, the student researchers convened to deliberate on the revised model for implementation in Round 2. The revised model’s key components are elucidated, and a comparative analysis between the initial and revised models is provided in Appendix 3, along with the underlying rationale. Figure 4 visually presents two Padlets used in both Round 1 and Round 2.

As shown in the Padlets, the preliminary three stages, encompassing the preview of articles for article selection, the sharing of one’s previewing process with peers, the selection of a specific article for in-depth reading, and the application of the TAR strategy during reading, have been amalgamated into a single phase termed “Embracing.” Within this consolidated step, students preview two or three articles and subsequently opt for one to be subjected to thorough reading, wherein they undertake the TAR task. Notable adjustments in the TAR task comprise the practice of audibly reading only sentences posing challenges, necessitating assistance from MT or ChatGPT.

Concerning vocabulary acquisition, the stipulated minimum count of words to memorize has been reduced to ten. Rather than relying on word frequency in the Collins Cobuild dictionary, the selection process integrates illustrative sentences. While the provision of a Korean translation for unfamiliar article words is suggested, it is not obligatory for the vocabulary log. The endeavor of identifying sentence types has been isolated from the TAR procedure. Students are directed to identify five sentences posing comprehension difficulties, furnish explanations delineating the challenges, input these sentences into ChatGPT, and subsequently juxtapose the outcomes with their own solutions.

In the composition phase, the requirement to draft in Korean has been waived. Instead, students initially write in English independently. Subsequently, their compositions are inputted into ChatGPT in two separate prompts: “correct” and “revise.” The format of presentation has been left to the discretion of the students, diverging from the prescribed template employed during the course and Round 1. The incorporation of Quizlet for the vocabulary log creation has been retained.

Compared to Round 1, Round 2 started with much more autonomy, allowing us to select various topics of articles. This marked a significant shift in fostering our self-directed learning methods. When we have autonomy in selecting articles, we felt a sense of responsibility and had the opportunity to delve deeply into the issues of our chosen articles. Through this process, it became apparent that our interest in specific fields led to a higher likelihood of increased attention to GCED rather than activities overly tied to the surface-level interpretation of themes within GCED. Focusing on article content, we considered the fundamental reasons and coping strategies behind various global issues, including those that might impact us directly. As a result, we aimed to understand just not only superficial meaning of “GCED themes,” but also the essence of specific issues more profoundly. This depth of understanding turned out to be crucial for the sustainability of this activity because it promoted a level of engagement.

Moreover, while the model developed from Round 1 could be simpler, Round 2 allowed us to express our opinions, reducing inefficiencies and adding necessary components. Shortening time was also a big factor, but the fact that we felt that it was a more efficient process for ourselves than before has greatly reduced the overall burden in proceeding with the CoP itself.

Regarding article selection, the autonomy allowed us to directly evaluate and choose articles based on our level. Contrary to expectations that foreign articles might be challenging, there were many articles that were too easy and accessible to enhance English ability, as well as articles that were too difficult to try with a large number of academic vocabulary. To maintain autonomy while fostering English proficiency, guidelines may be necessary to navigate this aspect.

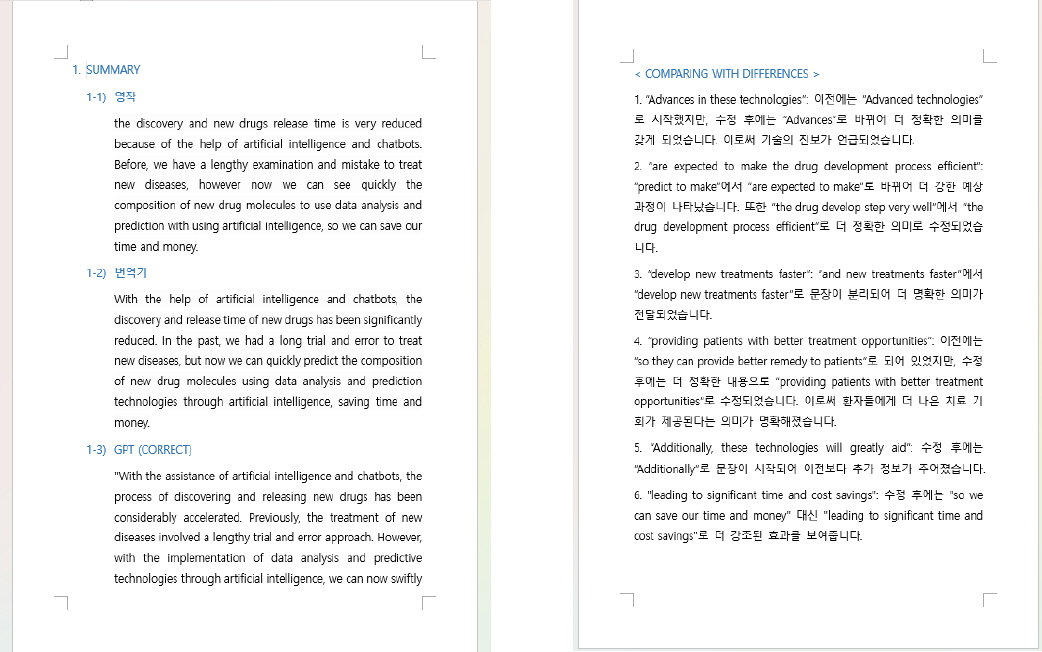

Another difference between Round 1 and Round 2 was that it required English composition right from the beginning. Despite this being a major concern for participants, the outcome contradicted expectations. All of us recognized this activity as the most essential part for the CoP. Developing English composition skills in a short time was an unanticipated result. Especially during the “COMPARING WITH DIFFERENCES”, participants compared their own compositions with ChatGPT’s suggestions, replacing vocabulary with more sophisticated synonyms and idiomatic expressions. Figure 5 shows a sample of a composition using MT and Chat GPT, and the “comparing with differences.”

We even explored more efficient approaches for utilizing ChatGPT’s capabilities among ourselves.

In essence, Round 2 aimed at developing our self- developed model. The revised model was able to lead to greater participation than expected, and this attempt was essential in the process of creating a “sustainable model” by responding to the fact that we all felt active changes ourselves. Reflecting on the reasons behind this modeling effort and contemplating improvement directions offered an opportunity to seek a model not just for a brief period of learning but for students who will need to continue learning alongside AI technologies. Such an attempt is the step that contains the best direction that participants should have in this CoP. Furthermore, not only did our motivation increase but our interest and engagement also increased in the learning process.

As participants, who would eventually utilize the model developed in collaboration with AI, we believed we could chart an effective direction for the model. Both the advantages and disadvantages of Round 1 were the urgency and coercion of time, which was of course necessary, but the “sustainable” model should lower the burden on students, be as efficient as it could, and be more accessible. Continually brainstorming various platforms and Chat usage methods to expedite CoP activities seemed to be the ultimate goal of this modeling process. Even if not all aspects were integrated into the model, participants could discover efficient learning methods tailored to themselves. Recognizing these efficient methods could enhance confidence when encountering articles. In addition, “improving English skills” is an additional effect when accessing articles, and the amount and quality of articles available vary, so you can know the existence of more data and raise interest in global capabilities. This CoP activity concluded with a more profound sentiment than becoming interested in English again: it highlighted the idea of learning English not only for the sake of interest, but as a means to elevate global competence.

Through the advancement of various technological tools, they play significant role in collaboration and learning. This section evaluates the functions and roles of diverse technological tools such as Padlet, Zoom, MT, and ChatGPT in our activities.

We found great convenience in managing and sharing team activities through Padlet. Padlet made it easier to check activity deadlines and to see the progress of other team members, which made the collaboration much smoother.

Zoom, equipped with meeting recording capabilities, facilitated the easy recording and sharing of important information. Additionally, the recording feature allowed us to refer back to the recorded material for recalling information when we couldn’t remember our own contributions. It allowed seamless collaboration without distance or time constraints. On Zoom screen, we could see articles, presenters, and translation content simultaneously, making it effective for TAR recordings, and it was considered more user-friendly compared to other technologies. An illustration of Zoom’s application in recording a TAR activity is provided in Figure 6.

While MT is employed for translation tasks, there was an issue of translations sometimes not aligning with context, limiting our use of MT. In situations where quick translation results were needed, such as TAR or discussions, we acknowledged the role of MT. However, it was emphasized that for more accurate translations, complete reliance on MT should be avoided

Many of us noted that despite ChatGPT’s grammatical weaknesses, its exposure to various texts made it greatly helpful for us to learn contextually appropriate translations and new expressions. Additionally, it was mentioned that when utilizing ChatGPT, formulating questions in English rather than Korean led to more favorable and accurate responses. However, participants also highlighted instances where ChatGPT occasionally translated into a mechanical tone, resulting in awkward sentences when compared to assessments by native speakers.

We emphasized the importance of not overly relying on current technology for learning and collaboration. How to learn English while using technology was a major issue we discussed. After such discussion, some of us deliberately tried to speak, write, or translate by ourselves before referring to ChatGPT or MT.

Furthermore, we recognized that ChatGPT occasionally struggled with sentence structure analysis. This indicated the need for provision of guidelines to help students utilize ChatGPT without confusion.

In conclusion, it was evident that the advancement of various technological tools significantly impacts collaboration and learning. Tools like Padlet, Zoom, MT, and ChatGPT were evaluated to actively support team collaboration and knowledge expansion through their respective features. Nevertheless, it was concluded that appropriate dependence and a critical perspective are crucial when utilizing these technologies.

This final section expanded our understanding of time and space, orienting to our future plans and the Global Citizenship CoP. We were to answer two guiding questions for this section. I will highlight some of the interesting responses. The first question was: “How far have you come from the periphery to the center of the Global Citizenship CoP?” For Yeonjae, she initially thought she was completely on the outskirts before the activities began, but responded that she had approached the center by about 50%. She explained:

I used to be interested in social issues, but I only thought about whether those issues would be a benefit or a harm to me, rather than looking at them from a global citizen’s perspective. However, through this CoP, I realized the seriousness of climate change, and subsequently, as I came across articles on various topics, I realized that it’s not just our society’s problems that affect me, but also the global changes affect me, which will soon impact our society. I also realized that thinking about various topics as a global citizen is, in fact, beneficial for my own development. (Excerpt from Yeonjae’s individual narrative)

Her view on global citizenship changed a lot compared to the beginning of this CoP. The reason she answered as “50%” rather than “100%” was because she felt she hadn’t had enough time to read more articles or think about more topics beyond what she already knew.

In my case (Sujin), I was able to move quite a bit from the periphery to the center. In the beginning of this CoP, I had no awareness of global citizenship and had no interest in global issues at all. However, during CoP activities, I came across various articles through other members, which allowed me to learn about global issues. This exposure gave me a sense of responsibility as a global citizen that I couldn’t ignore. Additionally, during preparation for presentations, I felt like I moved closer to the center. Thinking about the debate topic and considering, ‘What is my stance on this issue, and how should I act as a responsible global citizen?’ helped me get closer to the center.

Finally, So-Hyeon, during the initial individual interview, responded to the question of how she assessed her global competence by saying, “I’ve been participating in Model United Nations consistently since middle school, gaining new perspectives. Studying the situations in different countries regarding a single issue led me naturally towards becoming a global citizen.” This interview response shows that even before this activity, she was closer to the center of the Global Citizenship CoP and that this activity has brought her even closer. She mentioned that this activity provided many opportunities to listen to different perspectives, especially through Rounds 1 and 2, and that her experience has grown as a result.

The second question was: “How do you plan to continue approaching the center?” Our responses had common themes. We all believed that to cultivate sustainable global citizenship skills, we should not only rely on English articles but also explore various topics through news videos and other media. We expressed the desire to seek out foreign sources of information to acquire more knowledge, and we emphasized the need to find efficient and rapid AI tools to tailor our learning methods.

Moreover, we mentioned that we would continue to develop our global citizenship skills by voluntarily seeking out articles and utilizing media platforms like YouTube, even if they are not articles. We stressed that choosing topics we are genuinely interested in for our activities, rather than assignments handed to us, helped us grasp the material more quickly and increased our interest in becoming global citizens. We acknowledged that summarizing articles in our own words and organizing our thoughts after reading allowed us to genuinely absorb the content, and through this process, we felt we were truly growing. We expressed a desire to continue this activity.

In particular, Young-Hyeon had the following response:

What I felt during this activity is that I genuinely grow when I directly delve into foreign articles, search for them, and contemplate them. Since then, I’ve wanted to continue this activity. If there is the opportunity to use the sustainable model we’ve created this summer, I would like to work as a supporter helping other friends. I hope that other friends can also have the perspective to see the broader and more diverse world. (Excerpt from Young-Hyeon’s individual narrative)

When we read her response during the research meeting, many of us acknowledged the significance of this statement, seeing it as a good idea and something to emulate. MinJung commented the following in relation to the Young-Hyeon’s statement:

Some students who will take this course in the second semester have asked me about studying methods, whether the assignments are too difficult, or if there are faster ways to complete them. After going through this CoP, I think it would be good if those students do not to consider the assignments as mere tasks. We might be considered selfish because we will not take this course in the second semester, but it would be good to explain the meaning to those friends. Group activities like this might help them see it differently. I’m willing to go as a supporter to help them understand the value of this activity. (MinJung’s comment on individual narratives during research meeting)

So-Hyeon also commented on Young-Hyeon’s statement:

In the early part of this paper, there were two definitions of global competence [the UNESCO definition and the OECD definition]. In the direction of first definition [a global citizenship that recognizes interdependence and community], considering the problem of the lack of such a global perspective, this CoP model appears to be a stepping stone to solve that problem and progress towards being a global citizen. I think Young- Hyeon’s words show this perfectly. It’s an important statement. (So-Hyeon’s comment on individual narratives during research meeting)

These responses collectively show a desire to help others and demonstrate global citizenship. They highlight how this online CoP model can foster such a mindset. Within the Global Citizen CoP, we’ve moved closer to the center, and we now have a stronger inclination to help others on the periphery.

The findings underscore the multifaceted impacts of out-of-class CoP activities on students. Primarily, these activities brought about a transformative shift in students’ attitudes toward both English language learning and global issues. Through engaging with tangible real-world issues via tasks like TAR, personal response writing, and presentations, students transitioned from mere rote memorization and exam-oriented approaches to a genuine enthusiasm for utilizing English as a tool for meaningful communication and comprehending global challenges. This transformation enabled the students who were initially unfamiliar with global citizenship (the four students except So-Hyeon), to cultivate a profound interest in it through their CoP experiences.

Furthermore, the CoP demonstrated its efficacy in bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge obtained in the course and its practical application on their own. Students drew from their prior course experiences to effectively implement CoP activities. Simultaneously, they acknowledged having struggled with task completion in the prior course experience due to a lack of understanding regarding the purpose and interconnections between tasks. However, CoP involvement helped them recognize the value of each task, reigniting their motivation to learn English beyond mere task completion. By autonomously selecting personally appealing topics and independently exploring articles within CoP activities, students gained a sense of ownership over their learning journey. This autonomy empowered them to seek relevant information, fostering a proactive approach to learning beyond the classroom. This resulted in heightened English proficiency and global competence, with a shift from considering activities solely as language learning tools to valuing the broader benefits they offered.

CoP experiences also introduced students to collaborative tools like Zoom and Padlet, offering platforms for idea sharing, mutual learning, and interactive discussions. Acknowledging the significance of group participation and interaction, students found collaborative learning to be pivotal in sustaining their learning momentum, which positively influenced their ability to regulate their learning process. This emphasis on collaborative learning further encouraged them to take charge of their individual learning pathways, thereby contributing more actively to CoP activities outside the classroom. Such an environment fostered a strong sense of community and shared learning among participants.

Lastly, the CoP activities sparked a lasting interest among students to continue exploring global issues even after the CoP program ended. As participants shifted from the periphery to the center of the Global Citizen CoP, they harbored plans to continuously enhance their global citizenship skills. Their strategy involved exploring diverse media sources, seeking out foreign content, and utilizing AI tools effectively. Notably, one student, Young-Hyeon, suggested forming a support group to aid other students interested in implementing CoP activities.

From the students’ perspectives, two key factors emerged as crucial for the successful implementation of the CoP model. Firstly, a comprehensive understanding of the rationale behind specific tasks and their interconnections is vital for the effective implementation of such tasks to foster global citizenship and improve second-language proficiency. This transition from passive learners who simply complete assignments to proactive learners who engage meaningfully became apparent as a comprehensive understanding of the rationale unfolded. Secondly, the autonomy to choose what to read played a significant role. Participants recognized the importance of authentic interest in chosen topics for effective learning and growth as global citizens. This autonomy fostered a sense of agency in their learning journey, motivating them to tackle more challenging articles related to specialized issues beyond their comfort zone.

Turning to MT and ChatGPT, MT was acknowledged for its convenience in providing quick translations. However, concerns were raised about its contextual accuracy, prompting recommendations for judicious reliance. On the other hand, ChatGPT was praised for facilitating the acquisition of contextually appropriate translations and expressions. Participants discovered that formulating questions in English yielded better responses, and they acknowledged the need to avoid excessive reliance on technology for learning. Despite acknowledging its grammatical limitations, participants found value in using ChatGPT for language learning. Guidelines were proposed to assist students in effectively using ChatGPT, considering its occasional struggles with sentence structure analysis. Overall, while participants recognized the significance of technological advancements like MT and ChatGPT in collaboration and learning, they underscored the importance of balanced reliance and critical evaluation when leveraging these technologies.

In conclusion, the study highlights the profound and multifaceted impacts of out-of-class CoP activities on students’ attitudes, learning approaches, and global citizenship development. The CoP activities not only transformed students’ perspectives on English language learning and global issues but also successfully bridged the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. By fostering autonomy, collaborative learning, and a sense of community, the CoP model empowered students to take ownership of their learning journey and engage in meaningful exploration of global challenges. Moreover, the integration of technological tools like MT and ChatGPT provided valuable insights into their utility, with MT offering convenience tempered by contextual concerns and ChatGPT facilitating contextually appropriate language learning. Ultimately, the study emphasizes the necessity of balanced reliance and critical evaluation when leveraging these technologies. The findings collectively underscore the significance of fostering proactive learners with a genuine interest in global citizenship, thereby nurturing holistic growth and learning beyond the confines of the traditional classroom.

References

Carré, A., Kenny, D., Rossi, C., Sánchez-Gijón, P., Torres-Hostench, O(2022). Machine translation for language learners, Machine translation for everyone:Empowering Users in the Age of Artificial Intelligence 18:187.

Chang, H(2013). Individual and collaborative autoethnography as method, Edited by Holman Jones S. L, Adams T. E, Ellis C, Handbook of autoethnography, 107-122. Left Coast Press.

Dill, J. S(2013). The longings and limits of global citizenship education:The moral pedagogy of schooling in a cosmopolitan age, New York: Routledge.

Jang, E. Y(2022). Changes in teachers'perceptions of plurilingualism through participating in a community of practice, Journal of the International Network for Korean Language and Culture 19(3), 339-379.

Jolley, Jason R, Luciane, Maimone. (2022 Thirty years of machine translation in language teaching and learning:A review of the literature, L2 Journal, 14(1), 26-44. http://repositories.cdlib.org/uccllt/l2/vol14/iss1/art2

Keles, U(2022 Autoethnography as a recent methodology in applied linguistics:A methodological review, The Qualitative Report 27(2), 448-474. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5131.

Kim, E. Y., Oh, E. J(2023). Machine translation (MT) use as translanguaging in CLIL:A case study of EFL writing with MT in a General English course for global citizenship, English Teaching 78(4.

Kleinschmit, A. J., Rosenwald, A., Ryder, E. F., Donovan, S., Murdoch, B., Grandgenett, N. F., Pauley, M., Triplett, E., Tapprich, W., Morgan, W. (2023 Accelerating STEM education reform:linked communities of practice promote creation of open educational resources and sustainable professional development, International Journal of STEM Education, 10(1), 15.https://stemeducationjournal.springeropen.com/

Klekovkina, V., Denié-Higney, L(2022). Machine translation:Friend or foe in the language classroom? L2 Journal 14(1), 105-135.

Lave, J., Wenger, E(1991). Situated learning:Legitimate peripheral participation, Cambridge university press.

Lee, H. W., Lee, S. J., Lee, Y. M., Kang, S., Kim, H., Park, C(2017). An international collaborative study of GCED policy and practice (I), Korean Institute of Curriculum &Evaluation, https://doi.org/10.23000/TRKO201900002370.

이, 혜원, 이, 수정, 이, 영미, 김, 미지, 강, 신애, 김, 형렬, 박, 찬호(2017). 글로벌역량 교육 정책 및 실태 분석을 위한 국제 협동연구 (I), 한국교육과정 평가원.

Lee, K(2019 Rewriting a history of open universities:(Hi)stories of distance teachers, The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 20(4), 22-35. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v20i3.4070.

Lee, S. M. (2021 The effectiveness of machine translation in foreign language education:A systematic review and meta-analysis, Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(3), 157-175. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09588221.2021.1901745

Mynard, J(2020 Ethnographies of self-access language learning, Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal 11(2), 86-92. https://doi.org/10.37237/110203

.

OECD. (2018). PISA 2018 global competence, PISA https://www.oecd.org/pisa/innovation/global-competence/.

Oh, E. J(2021). Modeling a general English course integrating global citizenship and global competence, Korean Journal of General Education 15(4), 163-186.

Oh, E. J(2022). Integrating global citizenship and global competence into a general English course:A case study, Journal of Education for International Understanding 17(1), 93-156.

Pressley, M., Afflerbach, P(1995). Verbal protocols of reading:The nature of constructively responsive reading Erlbaum.

Smith, S. U, Hayes, S, Shea, P(2017). A Critical Review of the Use of Wenger's Community of Practice (CoP) Theoretical Framework in Online and Blended Learning Research, 2000-2014, Online learning 21(1), 209-237.

UNESCO. (2015). Global citizenship education:Topics and learning objectives.

Watson-Gegeo, K. A(1988 Ethnography in ESL:Defining the essentials, TESOL Quarterly 22(4), 575-592. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.291.

Wenger, E(1998). Communities of practice:Learning as a social system, Systems Thinker 9(5), 2-3.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Instruction for writing individual narrative:

Compose your English learning narrative, organized into five sections: 1) your English learning experience before the course, 2) your experience of Round 1, 3) your experience of Round 2, 4) your assessment of the role of technology, and 5) your strategy for participating in the global citizen CoP. Prior to writing, thoroughly review the data posted on the data padlet. This includes your individual interview notes, the first journal entry, the survey before the first group interview, the notes from the first group interview, the second journal entry, and the notes from the second group interview. Endeavor to incorporate relevant citations from this data in your narratives.

Appendix 3

- TOOLS