The Social Identity and Investment of Learners in an Adult EFL Program -A Case Study of Three Korean Learners

성인 EFL 프로그램에서 학습자의 사회적 정체성 및 투자-한국인 학습자 3명 사례 연구

Article information

Abstract

Abstract

This study leverages “Investment Theory” (Norton, 1995) to investigate English as a foreign language (EFL) when it comes to the social identity and investment of learners in an adult EFL program in South Korea. Using triangulation, this study examines how three Korean learners negotiated their social identity and English learning with regards to language investment. The data were collected via class observations, semi-structured interviews, and the EFL program’s class attendance sheet, from October 2019 to February 2020. The findings revealed that EFL learners’ social identity and investment, which can be negotiated and constructed over time, are diversified and changeable through the process of learning English. Lacking the daily language environment of English as a second language, EFL learners start learning English at school. As a result, a learner’s first English learning-related social identity is one that involves examinations and/or tests, while other social identities (e.g., those of a traveler, teacher, worker, volunteer, etc.) follow over time. When negotiating a learner’s foreign language learning, diverse social identities help promote language investment. Finally, implications for formal foreign language learning pedagogy are discussed within this study.

Trans Abstract

초록

이 연구는 ‘투자 이론(Norton, 1995)’을 활용하여 한국의 성인 EFL 프로그램에서 EFL 학습자의 사회적 정체성 및 투자에 대해 탐구한다. 다각화 기법을 통하여 한국인 학습자 3명이 언어 투자와 관련하여 영어 학습과 사회적 정체성을 조정하는 방식을 살펴 본다. 데이터는 2019년 10월부터 2020년 2월까지 수업 관찰, 반 구조적 인터뷰 및 EFL 프로그램 수업 출석표를 통해 수집했다. 연구 결과에 따르면 EFL 학습자의 정체성과 투자는 시간이 지남에 따라 조정되고 구축될 수 있으며 영어 학습 과정을 통해 다양화되고 변화할 수 있다. 제 2 언어 학습자로서 영어의 일상적인 언어 환경이 부족한 EFL 학습자는 학교에서 영어를 배우기 시작한다. 그 결과 학습자의 영어 학습 관련 첫 번째 사회적 정체성은 영어 시험에 대한 정체성이 되며, 다른 사회적 정체성(예: 여행자, 교사, 근로자, 자원 봉사자)은 시간이 지남에 따라 일어난다. 학습자의 외국어 학습 조정 시 다양한 사회적 정체성이 언어 투자를 촉진하는 데 도움이 된다. 정규 외국어 학습의 교수법에 대한 시사점을 다룬다.

1. Introduction

Identity denotes a correlation formed among people, activities, and the world over time (Wenger, 1998). Existing research on learner identities (Farral, 2008; Norton, 1995; Piller, 2002; Skilton-Sylvester, 2002) has demonstrated that learners’ social identities are complex, dynamic, full of power struggles, and continually reconstructed in social interaction through language. Norton (1995) found that learners’ social identities are related to the notion of investment. This concept was introduced in Norton’s 1995 study of the English learning stories of five immigrants in Canada, which described English learning as an investment influenced by learners’ identities (e.g. immigrant, mother, language learner, worker, wife) and multiple desires (e.g. better life for children, struggle for speaking rights) in a fixed-language social context. Therefore, language investment is intertwined with social identity, which is dynamic and changeable (Teng, 2019). Moreover, Norton and Toohey (2011) indicated that investment and identity can be combined to explore the relationship between learners and the social world, since learners’ various social identities and desires come from their different interactions with society.

Learners’ diverse positions in different social interactions (Farral, 2008; Norton, 1995; Piller, 2002; Skilton-Sylvester, 2002) have attracted significant attention in the field of applied linguistics, with scholars investigating learners’ social identity and language investment (Teng, 2019). However, most research on language and identity has examined English as a second language (ESL) learners and may not be representative of English as a foreign language (EFL) learners (Vsailopoulos, 2015). Therefore, this qualitative study examines EFL learners’ construction and negotiation in an EFL adult program in South Korea, investigating EFL learners’ language investment in terms of the interactions between EFL learners and the social world in which they live.

This paper first presents the theoretical framework. Next, it discusses the setting, research methodology, and data collection. Finally, the research findings, discussion, and pedagogical implications are noted. Overall, this study examines EFL learners’ language investment via the negotiation between their social identity and English learning by answering the following research questions:

1. How do learners in an EFL program in a Korean university perceive themselves while interacting with English learning?

2. How do EFL learners negotiate their social identities and multiple desires in their English learning, and to what extent do these identities shape learners’ commitment to their English learning?

2. Theoretical Framework

The extant studies show that the process of English learning can be understood through learners’ identities and investment (Darvin & Norton, 2015; Norton, 1995; Teng, 2019), since learners’ identity construction takes place through language learning, which involves different roles in a language environment and is closely related to English investment (Teng, 2019). Therefore, a learner’s language investment is influenced by his or her identity (Norton, 2013).

Social Identity: Social identity refers to how an individual understands his/her relationship with the world, how that relationship is constructed in time and space, and how the individual comprehends future potential (Norton, 2000). Thus, language learners’ social identity refers to how individuals perceive themselves in English learning (Norton & Morgan, 2013). In Identity—A Very Short Introduction, Coulmas (2019) indicated that identity formation is an ongoing adaptation to dynamic environmental conditions: that is, different language contexts construct learners’ varying social identities (Norton, 1995). Thus, learner identity in English learning can be understood as a fluid, dynamic, and discursive notion (Norton, 2011). This study illustrates EFL learners’ identities via an understanding of English language learning interactions in South Korea.

Investment: Norton (1995) proposed the term “language investment” based on Bourdieu’s (1977) concept of “cultural capital,” which is understood as a metaphor for value and suggests a wide array of values, faiths, perspectives, and thinking approaches that could produce increasingly valuable results for learners. Norton (1995) believed that language learners invest in language learning because they expect to receive higher payments or value in return in specific environments. Such payments or value could be symbolic (e.g. language, education, or friends) or material (e.g. social status, real estate, or money; Norton, 1995). Drawing on Ogbu (1978), the return on investment is contingent on efforts made through language. In this study, learners’ language investment represents EFL learners’ investment in English learning and illuminates the relationships among learners’ social identities in different learning conditions and the extent to which these conditions shape learners’ English learning commitments in the EFL program.

3. Literature Review

Since the 1990s, the research focus on second language acquisition (SLA) has shifted from individual learners to the interactions between learners and their social environment (Yin, 2017). Norton (1995) defined language investment as a relationship between learners’ identity and society, implying that learners who invest in their English learning will increase the value of their cultural capital (Norton, 1995). Previously, motivation theory (Gardnerw, 1985) was used to quantify learners’ commitment to learning a target language in SLA (Gao, 2003); however, Norton (1995) made the critical argument that motivation theory has not captured the relationship between learner identity and language learning. Due to complex social histories and multiple identities in various social contexts, learners must negotiate their many desires in acquiring a target language (Tian, 2019). Norton (1995) suggested that, compared to motivation, the concept of investment is more accurate in investigating the relationship between learners’ identities and desires in English learning, since learners’ identities evolve over time and exert significant influence over their language learning (Gao & Zhou, 2009). Thus, learners’ investment in English learning is equal to their investment in identity, since they invest in English learning in anticipation of a return: that is, the more they invest, the more they expect in return (Norton, 1995).

Although investment theory has gained significance in SLA (Swain & Deters, 2007), Price (1996) argued that, a struggling immigrant mother with multiple social identities in Norton’s (1995, p. 20) work, Martina’s case shows that one’s identity as a mother is constructed, not through language enviroment, but through an inner quality of the human subject. Building on this, Rui and Gao (2008) highlighted that individuals involved in investment theory are those with a rational mind in society, whose investment direction is decided by social structure and limited resources. Hence, this theory expands the horizon of SLA language education and research (Rui & Gao, 2008).

While, in ESL, social factors guide how learners learn English, EFL learners learn English primarily as a subject in the classroom (Ellis, 1997). Although EFL and EFL are in different language context, Norton and Gao (2003) investigated EFL learners’ identities and investments and demonstrated that identity and investment are principal considerations for both EFL and ESL learners. Rui and Gao (2008) reported that “investment” can be used for demonstrating the language learning in the EFL scenario, and Teng’s (2019) study of learner identity and learners’ investments in EFL learning showed that EFL learners’ identities are complex and dynamic, both shaped by and shaping learners’ English investment. Vsailopoulos (2015) found that learners’ identity negotiation within English learning in South Korea is a complex process, raising questions about learner language identity options and (dis)empowerment. Building on these findings, the present study explores EFL learners’ identities and investments in South Korea to address learners’ identity construction options in different learning conditions and the extent to which EFL learners are willing to invest in English.

4. Methods

4.1 Class setting

The studied class was an EFL program focused on learners’ communication skills, especially listening and speaking. The program consists of students planning to study abroad or prepare for foreign language competency tests (e.g. The International English Language Testing System), as well as other English learning enthusiasts. To attend this course, students had to visit a language center at a national university in Southwest Korea in their spare time after work or school. Each academic semester in this program runs for seven weeks, and students must pay for each semester separately. Thus, this program differs from regular school courses because learners must spend extra time (after work or school) and money (every seven weeks) for their English learning.

The focal class was held from 18:00 to 18:50, Monday through Friday. The teacher was a native speaker from America who had been in Korea for seven years and had taught EFL for three years. He could speak Korean and usually used Korean to clarify things related to local issues, like the local travel experience and daily life. This was considered a convenient method for supporting the learners in the class, all of whom were Korean.

The teacher began each class by chatting with learners about different topics, such as traveling, weekend life, and hobbies, for around 10 minutes. Then, he taught new words and expressions from the coursebook both English and Korean. Next, students practiced what they had just learned in individual groups for five minutes, after which the teacher practiced with the students one on one. Next, the students discussed the coursebook questions by themselves. Finally, every student presented his or her ideas based on the content learned in class.

Importantly, the only course evaluation was the students’ attendance; there was no entrance or exit examination. <Table 1> below presents the class information.

4.2 Participants

The focal participants were selected through purposeful sampling, which is a widely used method for selecting the best participants for qualitative research (Patton, 2002). Before beginning the research, the researchers asked the teacher’s permission to observe the class. Both teacher and class observations were used to select the focal students based on the following: (a) active classroom performances, (b) consistent attendance, and (c) interest in engaging in additional self-study group outside of the class. Finally, the researchers asked consent to participate in the study from three participants, all of whom were willing to participate in this study, Anonymity was preserved by replacing the participants’ names with pseudonyms.

The class had a total of 13 students: 2 university students and 11 individuals working in different industries. The students attended this class in their spare time, after school or work. The requirement for learners’ attendance was not as strict as that for regular classes in official schools. Since everyone in the class had a separate school or work schedule, their attendance for this class was not the same. After one semester of observation, we identified three learners with almost perfect attendance; these were also found to be more active learners in this class. To obtain further information, the researchers interviewed the teacher about the three selected students’ participation in the class. The teacher reported that the chosen students—referred to as Jack, Lucy, and Tom for the purposes of this paper—were top students with excellent performance. For example, Jack was always the first one to answer questions in class. Lucy sat next to Jack, and they responded quickly and correctly during in-class discussions. All three could communicate with the teacher in English, whereas others in the class could not; with the others, the teacher often had to speak Korean to help (teacher interview, in English, November 2019). In addition, Jack, Lucy, and Tom created a self-study group for extra learning, studying in a coffee shop near their EFL classroom or arriving at school an hour early every day for additional study. The study group completed review work first, including words and expressions they learned in the last class, then conversed using the reviewed words and expressions. They also spoke English throughout their individual study.

Jack, a primary teacher of math and art in Korean, was the most active learner with the highest class attendance class. He always sat at the seat nearest to the teacher and was usually the first to answer questions. He was so active in answering that the teacher sometimes had to ask others, despite him knowing the answered. Jack and Lucy always studied together in class and came to school one hour early for additional learning.

Lucy, whose attendance was similar to Jack’s, was a government worker who sat near Jack and engaged in a class discussion group with him. During the class discussion, this group generally responded first, and their responses usually received “excellent” and “good job” remarks from the teacher. Lucy also created a self-study English learning group with Jack and Tom.

Tom was a junior majoring in math at the national university in which the language center was located. Tom had an English class at his university, but he did not consider it helpful for his English learning. He had the third highest attendance in the class and generally answered questions after Lucy and Jack. Since he wanted to improve his English for volunteer work in three months, Tom also joined Lucy and Jack’s self-study group.

Although the three participants shared some similarities, such as high attendance, self-study, and active performance (e.g. fluent class communication, correct responses to coursebook questions, and prompt responses to the teacher’s questions), high attendance, and self-study, observations of their self-learning group (which arrived one hour early every day for self-learning) revealed different social identities and English learning (EL) investment (<Table 2>).

4.3 Data collection

After getting permission from the management office, the teacher, and all students in the class, we continuously observed two academic semesters from October to December 2019. During these two semesters, we attended class every Monday and Friday, observing learners’ discussions, presentations, attendance, and teacher-student interactions and noting them in the field notes. The study data were collected via class observations, semi-structured interviews, and a student attendance sheet.

4.3.1 Class observation

We observed the class two times a week for three months (September 30, 2019 to December 27, 2019) while taking field notes, recording the class setting, classroom activities, and students’ performances. With respect to class setting, we described how the students were placed in the classroom and how the focus students settled into groups. With respect to classroom activities, we noted how the teacher used different classroom activities to teach and how the students interacted with the teacher in class. With respect to students’ performances, we noted their discussions, responses to teacher’s questions, and presentations during the last 10 minutes of class.

4.3.2 Semi-structured Interviews

The semi-structured interviews were conducted once a week with the students individually in a coffee shop and once with the teacher in the classroom after class at the end of the first semester. All semi-structured interviews were held in English and lasted approximately 30 minutes. In addition, the researchers asked the teacher to clarify and offer more information on certain situations after every class observation. For example, why was Jack ignored when he raised his hand to answer a question, or why did only four students come to one class? Finally, when we finished the three-month class observation, follow-up interviews were conducted through an online chat group and email in January and February 2020.

The study participants did not live around English like the English teachers and translators. They also did not use English in their lives, since English was neither their native language nor an official language in South Korea (Nam, 2018). The observed class was a conversation class for which students paid and invested their free time (after work and school) every day. Therefore, the semi-structured interview questions explored the participants’ motivations to pay money and spend time learning English through this program. However, Norton (1995) argued that investment, rather than motivation, best captures the relationship between learners and society. Hence, the theme of the interview questions was changed to focus on their social identity and English learning.

The face-to-face interviews of the three focal participants were held once a week after the class on Mondays or Fridays. They were conducted with one person at a time and generally lasted 30 minutes each. During breaks or on holiday, the interviews were held in cafes or conducted via the Kakaotalk chat group. In January and February 2020, interviews were conducted through emails when the participants had their two-week break after finishing two semesters in December 2019. At the end of the first semester, we also conducted one interview with the teacher.

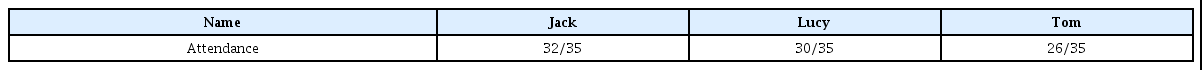

4.3.3 Course documents

The course lacked exams, tests, and graduations; its only assessment was learners’ attendance. Thus, we approached the management office to access the roll book for the target class, which recorded the attendance of all learners in the class. A total of 35 classes were held during the first semester (seven weeks, except for holidays). The three focal participants, Jack, Tom and Lucy attended 32, 30, and 26 classes, respectively. <Table 3> shows their class attendance.

4.4 Data analysis

Qualitative research uses methods like narrative inquiry, case study, ethnography, action research, and mixed methods in identity studies to elucidate and refine the dynamic and complex personal identities that exist in different language contexts (Heigham & Croker, 2009). Consequently, the present study utilizes a qualitative case study to explore the construction of EFL learners’ identities and investments. Triangulation can be used to ensure validity in case study research via data convergence in different areas, including findings, sources, and methods (Farquhar et al., 2020). Thus, the data in this study were collected via a triangulation of class observations, field notes, class documents, and semi-structured interviews with open-response items from focal learners and a teacher.

In the data analysis, the participants’ perspectives assisted in understanding EFL learners’ investment in English learning. The data were analyzed in two phases, highlighted by Charmaz (2006) as follows: (a) an initial phase and (b) a focused, selective phase. In the first phase of the study, 15 semi-structured interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed with the interviewees’ consent. In the second phase, we sorted and classified the class observation field notes and interview transcriptions into two categories: learners’ social identities and their English investment. The focused data were then selected from each word, line, or segment of data according to the two categories.

5. Results

5.1 Lucy: From student to worker, from motivation to investment

Lucy was an English major who majored in American literature. At the time of the study, she was working for her local government in Korea. She started learning English in primary school. In the EFL program, she insisted on engaging in group study with Jack and Tom one hour before EFL class every day because she believed they all wanted to improve their English for various reasons (e.g. traveling, job promotions, and volunteer work). She discussed her position in English learning as follows:

“…I go to… went to a class. I do not understand her [the former English teacher]. I do not know… I am an English major student… My English is not good…My score is not good… [smile and looks awkward]” (Lucy, original in English, student interview 1, October 2019).

Lucy, who was an English major, considered English learning to be a course. At the time of the study, she may not have realized the social context for English outside of school, because she did not mention any other identity beyond that of an English major student. For this reason, she discussed feeling terrible about not understanding her teacher’s English speaking well. In Lucy’s case, this was a necessary course that was influenced by English teachers and assessed as either “good” or “bad.” Both Gardner and Lambert (1972) and Gardner (1988) pointed out that instrumental motivation refers to learners’ pursuit of the values and advantages of the language they are learning. At the point of the study, Lucy believed that the “value” of learning English manifested as a “good score.” Since English was necessary for her major, she was motivated to learn English in order to get a good score. She also believed that an “English major student” should be good at English, although she felt she was not. This indicated a contradiction to her, leading her to feel nervous and awkward when she talked about her student experience in English learning. As a student, Lucy focused only on the relationship between English learning and school, meaning that her motivation to learn English was a “good score.” However, when she graduated school and became a worker in the local Korean government, her ideas concerning English learning had changed.

“I come here [the EFL program] because the teacher is come from America. I can learn speaking English from him. A lot of people can speak English [in Korea]… and if I can speak English in my job… I can have good thing in my workplace…” (Lucy, original in English, student interview 4, December 2019, during the individual study group).

Lucy viewed attending this EFL program as important because the teacher was a native speaker, and she felt that English could only be learned from a native speaker. Thus, instead of evaluating English learning by “score,” she realized the importance of the target language speaker’s authority. Since working in the local government, she began to focus on social context. As she mentioned, “a lot of people can speak English in Korea.” In addition, as a local government worker, she observed that “a lot of people can speak English,” noting that she now regarded English learning as a perceived benefit—a “good thing.”

As Norton (2015) remarked, English learning can enhance learners’ cultural, social, and economic capital and future benefits. By positioning herself within the local government, Lucy believed that she could get a “good thing” in return if she invested in English learning. Therefore, Lucy’s identity as a local government worker forced her to invest time and money in the EFL program and extra time in the self-study group. In Lucy’s investment, she constantly organizes and reorganizes a sense of who she is and the way in which she relates her English learning to her social world, which is diversified, contradictory, and changeable. In transitioning her self-identity from an English major student to a local government worker—and shifting her classes from school to society—Lucy’s transformed her English learning from motivation to investment.

5.2 Jack: From a student to a teacher; from score to skill

Only one-third of students attended the EFL program on Mondays and Fridays, which was the allowed fieldwork period. The teacher attributed this to “Monday and weekend syndrome,” suggesting that learners do not usually attend class when finishing a relaxed weekend or preparing for a relaxing coming weekend (teacher interview, November 2019). Nonetheless, Jack’s attendance was the highest in the program. He explained his English learning experience by drawing the following picture, with two distinct self-identities over time. Refer to <Figure 1> below.

“In the past, when I was a student, English was a score for test… my parent `said, ‘You must get high score. You must learn how to solve the questions on book. You must enter better university with high score’… My parents use their money to let me learn English. My parents want me to learn English because my parents want me to go to better university. But now, I am not a student, I have my money; I want to learn English with my money. I want to be move… I want use visa and world map to travel, so English is really important. English is a skill. There is no exam here… I can make friends and have interesting experiences…” (Jack, original in English, student interview 4, December 2019)

When interviewed about English learning, Jack mentioned the word “score” a lot. When he was younger, he believed that he could be admitted into a well-known university if he obtained a satisfactory English score. As demonstrated in the picture, when his social identity was that of a student, his English learning was driven by his parents and school requirements. He used “you must…” when discussing his English learning goals, demonstrating that he learned English passively as a student. He also had limited freedom when he was a student: he recalled his parents’ money and “parent want,” as well as “you must,” indicating that he had to listen to his parents’ or teachers’ instructions on English learning.

Conversely, “now,” with his social identity as a primary teacher, Jack used the words “my money” and “I want” to illustrate his new position in English learning, which was subjective and active. As shown in the picture, Jack wants to learn English “to be move” as a traveler not only because he has money was a primary teacher, but also so that he “use visa and a world map to travel” (student interview 4, December 2019). Thus, as he stated, “English is a skill” (student interview 4, December 2019). Norton (1995) highlighted that learners’ investment in language learning is equivalent to their investment in identity. When Jack was a student, English learning represented a “score” however, when he became a teacher, he invested in English learning for his future identity: one as a traveler who could speak English and make friends, yielding a symbolic return. It is important to note here that Jack’s identity as a student did not actively motivate English learning in his school, since all his references to early English learning involved the word “you.” However, in his new identities as a teacher and a traveler, he actively learned English in the EFL program and his self-study group after work every day. As an EFL learner, Tom changed his perception of English learning from a passive one to an active one—that is, from a “score” to a “skill”—as his identity changed from a student to a teacher and international traveler.

5.3 Tom: From student to volunteer, from school to society

At the time of the study, Tom was in his junior academic year, majoring in math. He said he began learning English in primary school. He came to the program to learn English because he planned to volunteer in Vietnam during the upcoming winter break as part of his vow to teach his major (i.e. math) in Vietnam. Although his mother tongue was Korean, as an international volunteer, Tom had to speak English or Vietnamese at work; since he could not speak Vietnamese, he went to the classes to quickly improve his oral English. He joined this EFL program and the individual study group every day after school despite having an English class at his university every week. When asked why he invested much time in English learning as a math major, he replied:

“I have English class in my university, but it is only for the class for English exam in my school… so I become teacher [volunteer teacher in Vietnam], so I want to teach them math… I think this is important to me, so I can use this in my resume… I hope I can improve my English very quickly.” (Tom, original in English, student interview 3, December 2019)

As a Korean student, Tom shared a perspective on English learning similar to that held by Jack and Lucy. All three believed that English learning was mainly examination-oriented in schools in South Korea. Nevertheless, when Tom got a chance to volunteer to teach math in English in the coming winter, he felt that learning English was his responsibility as a teacher. Because of his position as a math teacher and international volunteer who could not speak Vietnamese, he had to augment his oral English quickly. He said, “It [learning English] is important” to him because it allowed him to add desirable and professional performance in his volunteer job to his resume.

Norton (1995) remarked that language both constructs and is constructed by a learner’s social identity. On this note, Tom’s social identities included a math student, an EFL learner, an international volunteer, and a math teacher (in the coming winter). In pursuing English competency, he shifted his identity from a university math student to an international volunteer who needed to speak English. To accomplish this, he invested money and time in English learning. English learning can also be transformed into cultural capital, since teaching math in English is a competitive social experience that Tom could add to his resume. Thus far, Tom’s intertwined identity made his reasons for learning English outside of school clear.

6. Discussion

This study drew on three Korean EFL learners’ lived experiences via a case study exploring their identities and investments in English learning. The three participants started learning English when they were students; however, through interactions with the social world, their social identity constructions changed over time. In negotiating their social identity and English learning, English as “cultural capital” yielded various appealing experiences, including self-development, international traveling, and social experience. Although the identities of the EFL learners in this study are changeable, as are those of the ESL learners in previous studies (Farral, 2008; Norton, 1995; Piller, 2002; Skilton-Sylvester, 2002), this study’s findings could provide new insights into EFL learners’ investment.

First, EFL learners’ identities and English investments are diversified and changeable. Each learner in this study had varying social identities based on his or her interactions with society. In the English learning process, their social identities changed over time, taking on such roles as student, teacher, traveler, worker, and volunteer. Furthermore, in South Korea, EFL learners’ English learning interacts with the social environment via their social identities, because learners invest in English learning due to multiple desires rooted in social interactions, such as traveling abroad, earning a job promotion, and developing a competitive resume. Thus, like ESL learners, EFL learners’ social identities and English investments are also multiple.

Second, in the process of English learning, since the EFL learners in this study started learning English as a course in school, they constructed their English learning social identities from students into other realms, such as teacher, worker, or volunteer, over time. According to a study on language policy in South Korea, 28% of Koreans “use English frequently” in their daily life and work, whereas 58% of Koreans “use English occasionally” (Yin, 2017). Thus, though English is learned as an academic subject in South Korea (Dörynyei, 2000), it is not regularly used in a myriad of classes and professions. As a result, Korean English learners’ first social identities are constructed based on their roles as students, after which they may construct varying social identities. Further, school students view English learning as passive: something required by parents and schools in which they aim to get a high score or pass an exam. However, given its varying social identities (e.g. teacher, worker, volunteer), English learning has become “cultural capital” (Norton, 1995), full of various and appealing experiences.

Third, in the negotiation between learners’ social identities and foreign language learning, diverse social identities (e.g. teachers, workers, volunteers) encourage EFL learners to actively invest in English learning. Identity affects EFL learners’ investment (Teng, 2019). That is, learners are inspired to invest in English learning by their identities and further goals, while the investment in English learning is used to acquire richer materials and symbolic capital or to attain further goals with existing capital (Norton, 2015). Thus, in the present study, when the three participants were students in school, they only took classroom English courses and passed exams in their English learning. Outside of school, however, English proficiency was important for other goals, like for further goals like traveling, earning promotions, and accumulating social experiences. As a result, Jack, Lucy, and Tom were engaged in teacher, worker, and volunteer drivers that actively promoted their investment in English learning.

7. Conclusion and Implications

This study contributes to the qualitative research on EFL learners’ identities and investments on English learning in South Korea. Using triangulation, we identified three active learners in the EFL program according to class performance, attendance, and English learning out-of-class. To address the following research question—”How do EFL learners negotiate their social identity and English learning?”—we analyzed the stories of three Korean EFL learners as a case study of English learning. The findings highlight that the construction of EFL learners’ identity and investment in English learning is reproduced in South Korean social interactions and evolves over time; that “student” was the first social identity realized by the English learners in this program; and that the “student” learner identify had less impact than the other social identities (e.g. teacher, worker, international traveler, or volunteer).

Social identity enables learners to get close to a target language, for which they may choose to invest in more learning (Teng, 2019). We deem that, to counter complex learning contexts and problems in constructing social identity, EFL learners should consider and integrate different social identity and contextual positions. Hence, the present study suggests that EFL learners can be encouraged to diversify their social identities (e.g. teacher, traveler, worker, or international volunteer), instead of remaining students or EFL learners in their pursuit of English. This approach could help students alter their passive learning awareness and enhance their cognition of their interactions with society by using English in non-English-speaking countries. Alternatively, language investment can change learners’ lives, making it important to consider learners’ lived experiences and social identities in the language learning curriculum (Norton, 1995). This study suggests that EFL learners’ evolving situations (traveling, working, teaching) should be considered as specific and vivid aspects of EFL teaching that can arouse students’ interest in English learning.

In summary, we have sought to reveal the relationship between EFL social identity construction and English learning in this study, aiming to help EFL learners raise awareness of language investment in EFL environments. However, the study examined only a limited number of cases and research sites. Although the purpose of this study was not to generalize to all EFL learners, there is still a need for further research to examine the relationship between learners’ identities and their investments in EFL learning.

Appendix

Appendix

Interview guides

(To ensure that the interviews were undisturbed, only one participant was interviewed at a time. At the beginning, open-ended questions on English learning motivation were asked. As the research continued, the theme of the semi-structured interviews shifted toward learner social identities and English investment.)

1. When did you start to learn English?

2. Please introduce yourself (age, job, education background).

3. Why do you come to this EFL program? Do you think it is worthwhile to pay money and spend time to learn English in the program? Please share your reasons.

4. What are your expectations of your English learning? Why do you want to achieve such English competency?

5. Describe your English learning experience before the EFL program. Do you think you are a good English learner? Why or why not?

6. How did you feel about your English learning when you were in school? How do you feel about your English learning now? Are there any differences between your experiences of learning English in school and learning English in this program?

7. In addition to learning English from the class, what other efforts have you made to learn English?

8. Please describe what English is to you and explain why you think so?

9. Will English learning have any effect on your life? Why or why not?

10. If you were given another chance to make a choice of major, would you major in English? Please explain.

11. What are your future professional aspirations? Do you have plans to work outside Korea? If so, why?

![[Fig. 1]](/upload//thumbnails/kjge-2021-15-2-43-gf1.jpg)