A Case Study -Korean University Students’ Experience with and Perceptions of an Academic English Writing Class

사례 연구 -한국 대학생들의 학문적 영어 글쓰기 수업에 대한 경험 및 인식 조사

Article information

Abstract

The purpose of this case study is to examine Korean university students’ perceptions about the academic English writing class they took during the Spring semester of 2022. More specifically, this study aims to understand how satisfied students were with their learning experiences in the academic English writing class, and how they perceived its appropriateness as a mandatory English general education offered in the Korean higher education context.

A survey questionnaire consisting of Likert-scale, multiple choice, and open-ended questions was the main source of the data, and a total of 65 freshmen taking the course responded. To triangulate, in-depth interviews were also conducted with three focal participants via email or Zoom upon their choice. Descriptive statistics were calculated to analyze the responses to the Likert-scale and the multiple-choice questions, and the content analysis method was applied for open-ended survey questions and interviews.

Analysis of data showed that students viewed their academic English writing experiences positively due to the content knowledge and sense of achievement gained through the class as well as the instructor’s teaching style. Some participants were dissatisfied with their learning experiences because of content difficulty, relatively heavy workload, and their insufficient English proficiency which hindered them from following the class. Most students self-evaluated that their writing skills after the class somewhat improved. Students chose writing an essay, learning about academic writing conventions, such as APA styles and in-text citations, and instructor’s feedback as class activities that helped them improve their academic English writing.

To the question about the appropriateness of academic English writing as a mandatory general education subject, a vast majority of students hold a positive view. Their reasons include their belief of academic English writing as essential knowledge that they need to possess as a university student belonging to an academic discourse community as well as transferable knowledge needed not only in an English class but also in various disciplines. They also recognize its practicality for their academic activities and its rarity to learn anywhere else except university.

The findings suggest that school administrators should allocate more credit hours for an academic English writing course and offer it for students in their 2nd or 3rd year of university. The findings also emphasize the importance of instructors’ effort to tailor their instruction according to their students and to provide supplementary learning materials, such as pre-recorded videos so as to effectively guide students to improve their skills for English writing for academic purposes.

Trans Abstract

본 사례연구는 2022학년도 1학기에 학문적 영어 글쓰기 강좌를 수강한 한국 대학생들을 대상으로 수업에 대한 경험과 인식을 조사하는 데 목적이 있으며, 이를 위해 학문적 영어 글쓰기 수업에 대한 학생들의 만족도와 대학 필수 교양영어 과목으로서의 적합성에 대한 학생들의 인식을 조사하였다.

본 연구의 주요 자료는 설문지를 통해 수집되었으며 설문지는 리커트 척도, 선다형, 개방형 질문 등으로 구성되었다. 총 65명의 1학년 수강생들이 설문에 참여하였으며 이 중 3명의 참가자를 대상으로 이메일 혹은 줌(Zoom)을 통해 심층 인터뷰도 진행하였다. 리커트 척도 질문과 선다형 질문은 기술통계를 사용하여 분석하였으며 개방형 질문과 인터뷰 질문 분석에는 내용 분석 방법이 사용되었다.

자료 분석 결과, 대다수의 학생들은 학문적 영어 글쓰기 수업 내용과, 수업을 통한 성취감, 교수자의 수업 진행 방식 등에 만족도가 높은 것으로 나타났다. 이와 반대로 부정적인 반응 역시 나타났는데, 이는 대부분 수업 내용의 어려움, 학점에 비해 과도한 수업 내용 및 과제, 그리고 자신의 영어 능력 부족으로 인한 수업에서의 뒤처짐 등에서 기인하는 것이었다. 본 수업을 통한 글쓰기 능력 향상 측면에서, 많은 학생들이 대체적으로 긍정적인 자체평가를 내렸으며, 자신들에게 도움이 되었다고 느꼈던 수업 활동으로는 에세이 쓰기, APA 스타일 및 인용법 등과 같은 학문적 글쓰기 형식 및 규칙 학습, 그리고 교수자의 첨삭 등을 꼽았다.

학문적 영어 글쓰기가 교양필수 과목으로서 적합한지를 묻는 질문에 긍정적으로 답변한 학생들이 대다수였다. 그에 대한 이유로는 학문적 영어 글쓰기가 전문적 지식을 배양하는 학술 커뮤니티에 입문한 대학생으로서 반드시 지녀야 할 필수적인 지식이라는 점과 영어 수업 뿐만 아니라 다양한 학문 영역에서 필요한 전이가능한 지식이라는 점이 언급되었다. 또한, 대학이 아닌 다른 곳에서는 배울 기회가 적다는 점 또한 교양필수 과목으로서 학문적 영어 글쓰기의 필요성을 학생들이 인식하는 원인으로 나타났다.

본 연구 결과를 통한 몇 가지 제안점이 도출되었다. 학교 차원에서는 학문적 영어 글쓰기 과목의 이수 학점을 증가하고 더 많은 혜택을 위해 2학년이나 3학년 학생을 위한 수업으로도 바람직해 보인다. 또한, 학생들의 학문적 영어 글쓰기 능력 향상을 효과적으로 이끌기 위해, 교수자 역시 학생들의 특성을 고려한 맞춤형 수업 운영 및 녹화강의와 같은 보충 학습 자료 제공 등의 노력이 필요할 것이다.

1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of new information technology has enabled people around the globe to interact with one another without spatial and temporal constraints. In this increasingly interconnected and interdependent era, the necessity for English communication skills has only grown. In an effort to keep current with globalization, many universities in Korea have offered English-mediated courses (EMC) in recent years (Jon et al., 2020). This means Korean university students are required to possess English proficiency to perform various tasks in English while taking their majors. This may imply that everyday English communication skills alone may not be enough for them to pursue academic studies at tertiary levels (Hwang et al., 2020).

These circumstances have brought on changes in general English education in Korea. Specifically, Korean universities have started developing English for Academic Purposes (EAP) programs to strengthen the oral presentation and writing skills needed for academic achievements (Hwang et al., 2020). In particular, English writing has emerged as one of the core competences demanded for individuals in both academic settings and professional workplaces (Eriksson, 2018). They need to be able to write academic papers such as reports and essays in order to succeed at school. In addition, English writing is an important means of completing tasks and demonstrating expertise in the workplace after graduating from university. For these reasons, many universities in Korea require students to take academic English writing as a general education requirement in order to grow their competence in the global academic and professional world.

In spite of its growing popularity, however, relatively little attention has been paid to how academic writing is implemented in general English classrooms in the Korean higher education context. This study seeks to fill an existing research gap by providing in-depth descriptions of how academic writing is taught to first-year undergraduates as a part of the required general English curriculum. This study also attempts to investigate students’ learning experience and satisfaction level with their academic writing class and their perceptions of it as a required general education course in university. It is often said that Korean students tend to have greater difficulty with promoting writing compared to other English skills. This can be partially explained by the fact that not much attention is paid to English writing since the majority of high-stakes tests in Korea, such as the College Scholastic Ability Test, assess reading and listening comprehension (Jeon, 2018). By exploring insiders’ experiences, this study is expected to uncover student needs and work toward developing learner-focused general English education, specifically, academic English writing instruction. To this end, this study is guided by the following research questions:

How do Korean university students portray their experience of taking an academic English writing class at a university?

What are Korean students’ perceptions of offering an academic English writing class as a mandatory general education course?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview: English for Academic Purposes (EAP)

English for Academic Purposes (EAP) has emerged from the broader field of ESP (English for Specific Purposes). ESP courses are designed to teach English to meet the specific needs of learners, which is the most obvious difference from general English courses. The focus of these ESP courses is on the discourses and genres appropriate to learners’ specialty rather than on the language per se, such as grammar or language structures (Dudley-Evans, 2001). In other words, ESP courses typically aim to make learners aware of the particular ways in which the language is used in their field, so that they can communicate and perform tasks in professional settings.

ESP has been characterized as an approach to language teaching based on the learner’s needs. In this vein, Hutchinson and Waters (1987) stated that in ESP, “all decisions as to content and method are based on the learner’s reason for learning” (p. 19). Therefore, needs analysis, defined as “the systematic collection and analysis of all subjective and objective information necessary to define and validate defensible curriculum purposes that satisfy the language learning requirements of students within the context of particular institutions that influence the learning and teaching situation” (Brown, 1995, p. 36), has played an integral role in developing ESP courses. Due to its focus on identifying learners’ needs, ESP is often considered to be a more learner-centered language teaching approach.

EAP is generally regarded as a branch of ESP and is defined as teaching English to facilitate learners’ study or research in that language (Jordan 1997). EAP is based on similar theoretical foundations to ESP, but it is tailored to the needs of learners at various, usually higher, educational levels. More specifically, according to Hyland and Hamp-Lyons (2002), the characteristics of EAP include:

It draws on a range of interdisciplinary influences for its research methods, theories and practices. It seeks to provide insights into the structures and meanings of academic texts, into the demands placed by academic contexts on communicative behaviors, and into the pedagogic practices by which these behaviors can be developed. (p. 3)

EAP has developed rapidly to become mainstream in English language teaching and research (Hyland & Hamp-Lyons, 2002). It is generally divided into English for general academic purposes (EGAP) and English for specific academic purposes (ESAP). EGAP courses are typically concerned with core skills or study skills, and their examples vary depending on the type of class, which Jordan (1997) calls “a study situation” (p. 7). One example of the study situation is writing essays, reports or research papers, and the study skills in this case include summarizing, paraphrasing, synthesizing, using quotations, and so on. On the other hand, ESAP courses deal with subject- specific skills and language, and therefore, their purpose is to acquire the specific language of a single discipline, such as chemistry or economics.

As English as a medium of instruction (EMI) has been commonly adopted due to the internationalization of tertiary- level institutions, the need for EAP has increased accordingly. In the EMI classes, subjects are delivered wholly or partially in English, and this means that non-native-speaking students inevitably face great challenges when studying their major in English, leading to a growing need for systematic support for students’ learning on an institutional level by providing EAP courses (Crawford Camiciottoli, 2010).

Among various academic skills, the importance of writing has been emphasized by many scholars for several reasons. Writing is considered the most challenging task for language learners. It does not come naturally; students need explicit instruction to know how to write (Nunan, 2000). Björk and Räisänen (2003) asserted that writing should be included in all higher education settings not only because of its immediate practical application, but also because of its role as a tool for “critical thinking” and for “learning in all disciplines” (p. 8). In other words, writing is viewed as a necessity in many disciplines (Jalleh & Mahfoodh, 2021). More specifically, students are required to have a command of writing skills in order to demonstrate their understanding of concepts and/or theories and to express their new thoughts and ideas in their courses. This very productive language skill not only helps students to achieve academic success but also serves them far beyond the confines of classrooms, in their profession after graduation from college (Hyland, 2019).

2.2. EAP in Korean Higher Education Contexts

In spite of the increasing attention to EAP, there is a paucity of research in Korean higher education contexts. The current literature on the topic is limited to analyzing undergraduate students’ need for EAP and overall satisfaction with it. For example, Hwang et al. (2020) analyzed 673 college students’ needs for EAP in order to design an EAP program model. The respondents expressed their dissatisfaction with their general English courses, noting that they did not help them to gain the English proficiency needed for their academic studies. The participants also had strong desires to take EAP courses which are relevant for their own disciplinary fields. Based on these findings, Hwang et al. suggested that it is necessary to develop EAP programs to enhance students’ English ability for accomplishing academic tasks.

Cha and Kim (2021) examined whether EAP courses focusing on reading and listening met English learning needs of Korean university students majoring in science and engineering. The participants expressed satisfaction with the course since they felt it enhanced their overall proficiency levels and motivation for learning English and reported that they wanted to learn more about academic English writing, which was not covered in high school English classes. Cha and Kim asserted that these learning needs should be reflected so as to implement more effective EAP courses and argued that students’ motivation for learning English will increase if content-based academic English relevant to their major is adopted.

Yi (2016) implemented task-based English reading for academic purposes, asking Korean university students to complete one of 10 different tasks, such as representing the content using a table or a picture, each time when they read a part of the textbook throughout a semester. Yi then investigated how the participants felt about their learning experiences and found out that they perceived the tasks as helpful for developing their EAP reading skills. However, the students expressed that the tasks involving writing, such as writing a book report or summarizing content, were unfamiliar and challenging for them. From the results, Yi suggested that EAP courses are much needed at university considering that students have to deal with textbooks written in English for their major study, which can cause great challenges. On top of that, she argued that academic writing should be taught to address students’ difficulties with the skill. She also emphasized that students’ needs should be analyzed with caution when designing EAP courses since they are likely to be influenced by various factors, such as proficiency levels and previous learning experiences.

Most studies on EAP in Korean higher education contexts have focused on either college students’ needs analysis for EAP or their experiences with taking reading- focused EAP courses. One exception can be found in Lee’s (2022) study of academic English writing classes at a science/engineering research university. The classes were designed to assist undergraduate and graduate students in taking English-medium courses and publishing international journal articles. Depending on students’ English levels, the aim of each class varied from writing paragraphs to writing research papers, but the topics all centered around their disciplines (i.e., science and engineering). Students expressed a strong desire for English writing instruction that can meet their academic needs in their disciplinary field. Based on the results, the author emphasized that universities should provide students with purpose- or needs-specific English writing courses according to their majors. While this study is significant in that it examined students’ perceptions of their actual academic English writing experiences, it should be noted that it was conducted in a research university with both undergraduate and graduate students. The findings cannot be generalized since the students attending a research university might have different needs for academic English writing from their counterparts in other types of universities in Korea.

As the cited studies imply, there is an increasing need for including academic writing in English language education at tertiary levels in Korea. However, there is a dearth of empirical research that addresses the actual practices of academic English writing instruction in the Korean higher education context. The current research was conducted to fill this gap in the literature and aims to describe how a college English course focusing on academic writing was implemented and how students responded to their learning experiences. This study also analyzes how students perceive the appropriateness of academic English writing classes as a required general English education course. This line of research is expected to shed light on how to not only develop effective academic English writing courses but also design college English education in ways that better assist students for their academic success.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Context & Participants

Data for this study were collected from eight classes of the mandatory two-credit general English course taught by one of the researchers in a four-year university located in the Seoul Metropolitan area in the Spring semester of 2022. Each of the classes was for intermediate level and met once a week for 100 minutes over the 15-week semester. The instructor used English during class and implemented an English-only policy for students to improve their English skills. Academic writing was an essential part of the course curriculum, and emphasis was placed upon how to present and support a position using various sources when discussing the topics relevant for academic and professional settings. Weekly teaching and assignments were designed to meet these goals as shown in Table 1.

Throughout the semester, students were required to develop a three-step writing project, which consisted of opinion paragraph writing, annotated bibliography, and essay writing. The main contents of the weekly class meeting dealt with the necessary academic writing skills students should acquire to complete each step of the writing project. At the beginning of the semester, students were asked to choose a topic from the main textbook of the course (e.g., animals, environment, and transportation). Each topic features an opinion prompt for opinion paragraph writing (e.g., “Some people support automation (using machines to replace human jobs) and others are against it. What is your opinion?”) and a research prompt for annotated bibliography and essay writing (e.g., “Some futurists have talked about the way automation could cause massive job losses, and suggested solutions to the problem of unemployment caused by automation. Research a few of these solutions, explain what they are and who is suggesting them, and discuss the good and bad sides for each.”). Since the research prompt was meant to expand the ideas from the opinion prompt, students were supposed to choose an opinion prompt and a research prompt as a set in the same topic (e.g., discovery & invention). For the first step, opinion paragraph writing, students were required to write 10-12 sentences consisting of a topic sentence, supporting sentences and a concluding sentence for the opinion prompt of their choice. For the following step, students had to find three academic sources (e.g., book or journal article) relevant to the research prompt and provide reference entries in APA style and a summary for each source. As the final step, students completed a five-paragraph essay including the citations and summaries from the previous step in an annotated bibliography.

Before submitting each piece of the writing project, some class time was allotted for peer feedback in which the students sat in groups to read each other’s writing. Based on the feedback received from their group members, students revised their first draft and then submitted the writing assignment. After students submitted their opinion paragraph and essay in weeks 5 and 14, respectively, the instructor met with individual students for a writing conference. Due to time constraints, the writing conference was on a voluntary basis, but approximately 80% of the students participated. For those who chose not to participate in the writing conference, the instructor provided written feedback by inserting comments in Microsoft Word. For the annotated bibliography, the instructor originally planned one session of peer feedback. However, students had great difficulty formatting reference entries in APA style, so the instructor ended up giving two peer feedback sessions. During the peer feedback, the instructor observed students closely and offered assistance when needed, and she provided every student with written feedback as well. For each step of the writing project, students were given the second chance to resubmit their assignment after revising their drafts based on the feedback they received from the instructor.

A total of 65 first-year students participated in the current study. The participants were from various disciplines, such as Engineering (29.3%), Information Technology (26.2%), Economics and Commerce (21.6%), Social Sciences (6.1%), Natural Sciences (6.1%), Law (6.1%) and Convergence Specialization (4.6%). Students were asked to self-assess their English proficiency levels; approximately 59% reported being intermediate or higher, and a significant proportion (73.8%) responded that they consider themselves most lacking in speaking, followed by writing (53.8%). In addition, 54 out of 65 students (83.1%) said they had never learned about writing a paragraph or an essay in English. More than four-fifths of the respondents (81.4%) believed that the ability to write in English is important, and only one thought otherwise. The remaining students (16.9%) took a neutral stance.

3.2. Data Collection & Analysis

A survey questionnaire provided the primary data for the current study. The authors created the survey questions in Google Forms, and the links were made available on the online Learning Management System (LMS) for the students to access out of class so that they could participate in the survey voluntarily. A total of 65 students answered the questionnaire. The survey contained a total of 30 items which consisted of 5-point Likert scale, multiple-choice, and open-ended questions. All the questions in the survey were written in Korean, the first language of the respondents for easier understanding. Every student chose to answer in the same language, and all the responses were translated into English for research publication purposes. The first nine questions asked the participants’ demographic information and their English learning experiences. The rest of the questions sought the students’ satisfaction with the academic English writing class and their opinion of its appropriateness as part of the mandatory English general education program.

In addition to the survey, interview data were also collected. The instructor recruited students who might be interested in in-depth interviews by creating an announcement in the LMS. To ensure the students’ voluntary participation, the announcement was posted after the final grades were released when the 15-week curriculum was over. Three students (referred to by pseudonyms in this study) responded to the invitation: Minjae (Organic Materials & Fiber Engineering major), Joonsu (Journalism, Public Relations & Advertising major), and Yuna (Lifelong Education). Minjae and Joonsu chose email, and Yuna preferred Zoom as the mode of interview. The main purpose of the interview was to member check the questionnaire responses including but not limited to the ones to the open-ended questions.

Other supplementary data included various types of artifacts such as students’ writing samples from the three-step writing projects, weekly teaching materials, communications between students and the instructor via email and LMS message, and the field notes recorded by the instructor. These data served the purposes of better understanding the students’ participation in the academic English writing class and their perceptions of it as well as triangulating the primary data sources.

The survey was created using Google Forms, and participants’ responses were automatically saved and organized in a spreadsheet. In order to figure out students’ satisfaction with the academic English writing class and their perceptions of their learning experiences, their responses to 5-point Likert scale and multiple-choice questions were analyzed employing descriptive statistics (e.g., frequency count and percentages). The responses to the open-ended questions from the questionnaire and the interview questions were translated into English as the first step of the analysis. Then each researcher closely read the transcripts, paying attention to any repeated words or phrases in an attempt to identify emerging themes. After this individual analysis, the researchers shared their initial interpretations and tried to reach agreement through discussions if there were any discrepancies in analysis. The researchers used secondary data, such as students’ writing samples, for validation purposes by cross-checking the survey and the interview results.

4. Results and Discussion

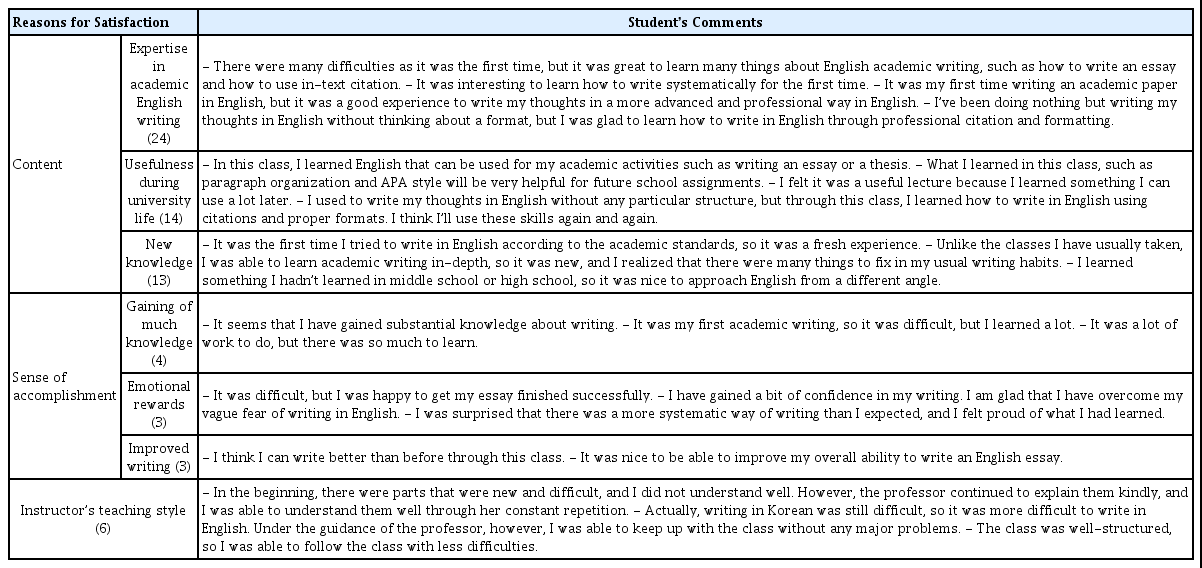

4.1. Students’ Experience of Taking the Academic English Writing Class

The first part of the survey centered on the students’ thoughts about their experience of taking the academic English writing class. Question 1 asked how satisfied the students were with the class in general. The vast majority (83%) responded that they were satisfied (61.5%) or very satisfied (21.5%), and the rest took a neutral stance (10.8%) or said they were dissatisfied (6.2%). The students were asked about the reasons for their satisfaction in Question 2. The most frequently mentioned reasons were the content knowledge, a sense of achievement, and the instructor’s teaching style (Table 2).

The most frequently stated reason for their satisfaction with the class was the content about academic English writing covered in the class. Students were pleased to learn about academic English writing because they believed it made their English writing more “professional.” They were glad to have a chance to gain specific knowledge about academic English writing, such as essay structure, in-text citation, reference formatting, and writing mechanics, which they saw would enable them to write more “academically” in English and would make their writing more “professional” to be accepted as proper writing in academia. In addition, participants highly valued the content taught in the class since it included knowledge and skills that would be needed “a lot more later,” towards the end of their university life when they would have to write academic texts like a thesis. For some students, the content they learned in the class was different from what they had learned in English classes during their secondary school years, so learning about academic English writing was a “new experience” and they felt “fresh” about learning English. All three interview participants also noted that writing a long text like an essay and learning about the formal format of writing felt new to them. Minjae stated:

This was the first time that I wrote an academic essay in which I expressed my arguments and opinions in a standardized format. This formal writing was different from the English I had previously learned, and I felt it was a fresh, new way of learning English.

The next main reason for students’ satisfaction with the academic English writing class was their sense of achievement. Although they acknowledged that the content was difficult and the class required a lot of work, some students commented they were satisfied because they eventually learned “a lot” and gained “substantial knowledge” about academic English writing. Through the knowledge and practices covered in the class, some students even enjoyed their improved writing skills. Emotional rewards were also found to be an attributable factor. Some students reported that they “overcame a vague fear of English writing” and “felt proud” of what they learned.

Lastly, the instructor’s teaching style also appeared to contribute to students’ satisfaction with the class. In the beginning, students seemed to feel that the class was confusing because the content was unfamiliar and difficult to learn, but they successfully completed the class in the end thanks to the instructor’s considerate guidance. They were impressed with the instructor’s continued effort to offer feedback to students even when many questions were asked and with her ability to plan out the lessons so that they were easy to follow. One student even commented that “the class system was optimized enough to fulfill the goals of the class.”

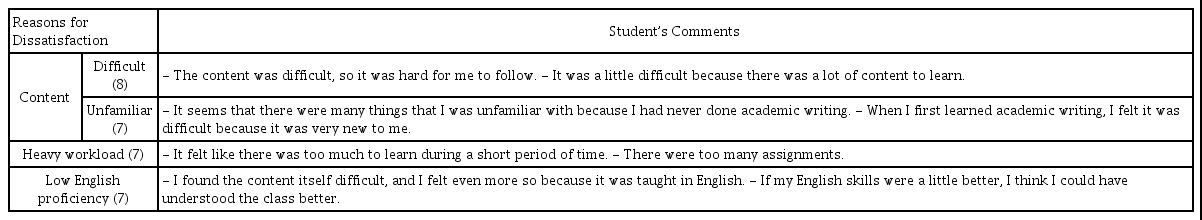

Reasons for students’ dissatisfaction with the class were also explored in Question 3, and the following four were distinctly mentioned: difficult content, unfamiliar content, heavy workload, and low English proficiency (Table 3). Many students were satisfied with the class because the content was about academic English writing and because it was new and different from what they had learned so far. However, for some students, the same reason caused dissatisfaction because it made the content more “difficult” to learn. On top of that, the amount of content and homework assignments was perceived to be “heavy,” given that the class was a two-hour, two-credit course. Lastly, the medium of instruction in the class was English, and some students pointed out that the English-only policy made it harder for them to keep up with the class.

The next survey questions focused on exploring students’ improvement in writing after taking the class. Question 4 asked whether their English writing ability had become better than before they took the class. About 77% of the students responded that they agreed or strongly agreed that their current English writing skills improved, and the rest were neutral (20%) or disagreed (3.1%). The agreement rate shows that the students felt improvement of their English writing by the end of the semester in general, but not many students seemed to be strongly certain about their improvement, given that a relatively small percentage of students (20%) strongly agreed compared to those who agreed (57%). In the same vein, Questions 5 and 6 asked students to self-evaluate their own English writing levels before and after the class, respectively. The meaning of each writing level was operationally defined in the survey based on ACTFL (the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages) Proficiency Guideline for writing (n.d.) and the course objectives. As Table 4 shows, about 29% of the students responded that their writing was at level 1 or 2 before taking the class, but it dropped to 4.6% at the end of the class. This shows that many students believed that they were able to do at least paragraph-level writing in English by the end of the class. In addition, 10.7% of the students rated their writing at level 4 or 5 before the class, but it increased to 50.7% at the end. This also shows that more students felt that they were able to do essay-level writing than before they took the class.

Question 7 inquired about what class activities and assignments students perceived to be helpful for improving their writing skills. Their responses are presented in order from most to least helpful in Table 5. A task to write an essay was the most highly rated activity (53.8%), followed by the writing task to practice APA referencing and citing styles (47.7%), the instructor’s lectures (43.1%), and the instructor’s feedback (43.1%). It was also found out that the essay writing task (53.8%) was perceived to be more helpful than the task to write a paragraph (36.9%), and the instructor’s feedback (43.1%) was considered more beneficial than the peer feedback activity (29.2%). In addition, the individual writing tasks such as essay writing (53.8%) and paragraph writing (36.9%) were perceived as more helpful than the group writing activities carried out during the class time (20%).

In the light of favoring essay writing over paragraph writing, the three interviewees mentioned that it was because the former required more attention to what they had learned about academic writing due to its longer text. In addition, essay writing took a longer time to complete than paragraph writing, so Yuna mentioned that she had enough time to review what she had learned in class more thoroughly.

Unlike paragraph writing which was easier because I just needed to find sources for only one argument, I had to search for different sources for multiple arguments with APA citations and references. Through essay writing, many students may have felt that they have learned more from more advanced tasks. (Minjae)

I thought that students can improve their English writing ability while writing the complete content whereas a paragraph is to write only a part of my argument. (Joonsu)

I was able to write with more time to prepare for the essay writing activity, taking a lot of time to think and frequently referring to what I have learned. Besides, since I have to look for more evidence to support my argument in the essay than in the paragraph, I should stay more alert to the things that I have learned so far. (Yuna)

Regarding the less helpful group activities, the three interview participants pointed out a lack of time to build rapport with group members and types of group activities. Joonsu and Yuna stated that if group work had started much earlier, not in the middle of the semester, they could have been closer to one another, which would have created a more “comfortable environment” for group activities. Furthermore, Yuna and Minjae mentioned that some group activities like peer-reviewing were helpful, but those like in-class writing tasks were not because of the limited time they were given; every in-class writing task required each group to present their writing outcomes at the end of the task, so students were pressed for time and therefore a few students who had high English proficiency ended up contributing to the task.

I remember that this activity didn’t happen in the first place. It happened after the mid-term course evaluation. If this activity had been carried out from the beginning, I think the intimacy with the members would have increased and more active group activities would have been made. (Joonsu)

I think the reason may be that group activities started after the middle of the semester. I think people can express their opinions well in a comfortable environment, but for example, there was a shy group member in my group and she didn’t say a word. And each group had to share their group writing at the end of each class, and group members seemed to rush just to get it done. (Minjae)

In terms of creating sentences with group members, there was not enough time given. That’s why only a few efficient group members did the tasks, so the meaning of the group work could not be found. However, peer feedback activities were very helpful because it eventually made me realize the problems in my own writing. (Yuna)

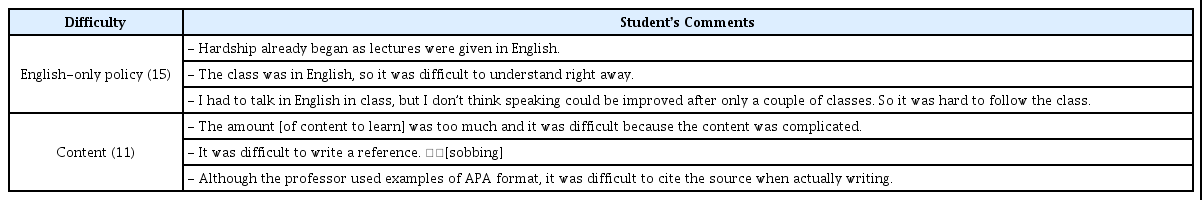

Participants were also asked what difficulties they experienced during the class in Question 8. Their answers overlapped with the reasons for their dissatisfaction in many aspects (Table 6). Out of 28 respondents who left comments about their difficulties, 15 noted that they had difficulties accurately and instantly comprehending what they were learning in class because the medium language of instruction was English and they sometimes ended up missing out on some important content. As a student stated in his comment, “Hardship already began as lectures were given in English,” it was not easy to follow the academic English writing class taught in English for some students. The next type of difficulty was related to the content: 11 participants reported that learning content about academic English writing and applying it to writing tasks were already difficult, and it was made more complicated because too much new content was covered within a short period of time. As for minor difficulties, a relatively high volume of assignments and communication difficulties between group members were also commented on.

In line with their difficulties, Question 9 asked specifically about the writing skills taught in the class that were difficult to learn. As seen in Table 7, citing and referencing in APA style (41.5%) and developing paragraphs or essays in a logical order (41.5%) were the most difficult tasks, followed by paraphrasing (30.8%), using proper vocabulary in writing (30.8%), using grammatical forms (19.2%), and using proper mechanics of writing (12.3%).

4.2. Perceptions about Academic English Writing as a Mandatory Course

The second half of the survey sought to examine how students perceive offering an academic English writing class as a mandatory general education course at university. In an attempt to understand their general thoughts on English writing, Question 10 first asked what areas of English should be taught at university. Speaking was selected the most (81.5%), followed by writing (56.9%), listening (29.2%), and reading (27.7%). Students were also asked what areas of English could be effectively taught in a limited environment like a university classroom setting during a class time of two hours a week (Question 11). Writing was perceived to be most effectively taught (61.5%), followed by listening (38.5%), speaking (30.8%), and reading (26.2%). To Question 12 asking whether English writing skills are important in university, 81.5% affirmatively said that they agreed (56.9%) or strongly agreed (24.6%), and the rest were neutral (16.9%) or disagreed (1.5%).

The responses to these three questions show that students viewed English writing skills as important to learn in university. They considered output-oriented English classes (i.e., speaking and writing) to be more suitable for Korean university students to take than input-oriented English and believed that more effective results would be had in a writing class in a university setting than in listening, speaking, and reading classes. Regarding the reasons for choosing writing as an area of English to be effectively taught in a limited learning environment, Joonsu and Minjae commented that it was because students would be able to learn “tangible skills,” such as how to organize thoughts logically and how to write in APA style, and to produce a “tangible result” (i.e., an essay) that showed their progress:

I think that writing can be learned more effectively in a short period of time compared to other areas. Although it is still hard to write in English and I don’t think my writing in general has noticeably improved even after the class, I now know how to use APA styles in writing and I can also write logically in English. (Joonsu)

Just by following what I learned in class even without using much extra time, I was able to produce an essay consisting of five paragraphs. Many students were also satisfied that they wrote an essay that expressed their arguments in an efficient manner at the end of the class. I think that is one of the reasons why writing is a good subject to teach within the limited class time like the one we had, two hours per week for 16 weeks. (Minjae)

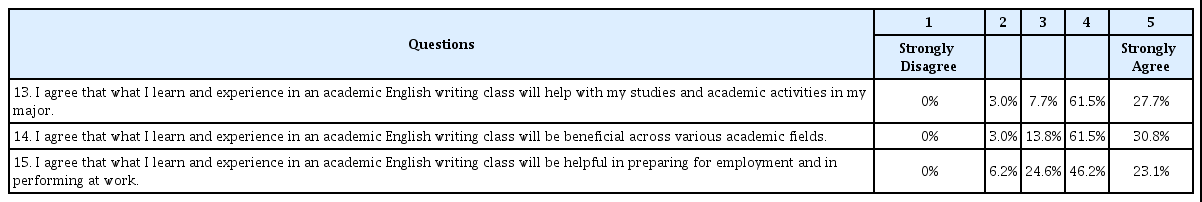

The next batch of questions (Questions 13-15) explored how helpful students think academic English writing skills would be for their academic activities in general (Question 13), across various academic fields of study (Question 14), and in their preparation for and/or after employment (Question 15). As shown in Table 8, about 89% of the students answered that an academic English writing class would help with their studies and academic activities in their major fields, and about 92% felt that it would help across various academic fields. In comparison to these high agreement rates, the students seemed to agree less on its usefulness for employment preparation and job performance at work; 69.3% said they agreed or strongly agreed, but 30.8% chose “neutral” and 6.2% “disagree.”

In the last two questions (Questions 16 and 17), students were asked their opinions about whether it is appropriate to have an academic English writing class as a mandatory general education course at university and what their reasons are behind their answers. More than four-fifth of the students responded that they agreed (46.2%) or strongly agreed (38.5%) with having academic English writing as a mandatory curriculum for university students; only 10.8% of the students remained neutral and 4.6% disagreed. In response to the open-ended question asking about the reasons for their choices, 37 comments were made in total, all of which except for one were in favor of making it mandatory. The main reasons for their agreement are set out in Table 9.

Participants’ agreement that academic English writing is appropriate as a mandatory course at university was rooted in their strong belief that it is a genre of English that all university students should know. Academic English writing was recognized as “required,” “unavoidable,” and “essential” knowledge at university; some students stated that university students should learn it “at some point” of their university life and even “make time to learn [it]” if they haven’t learned it yet. As a student commented, “We live in a global world. Thus, if we are anything of a university student, we should be able to write at least an essay in English,” the ability to write academically in English was considered as an integral part of their identity as a university student.

All three interviewees also agreed that academic English writing is what university students do, and therefore it is appropriate to offer it as a mandatory general English course at university:

University is a place where academic writing is taking place. And academic English writing is often necessary, so I think it’s appropriate for university students to learn in that area. (Yuna)

Before coming to university, the majority of students had no direct experience with academic writing. However, it is difficult to avoid the situation of having to deal with academic writing, so it is appropriate for university students to learn it. We have just started our academic study, and we can feel at ease in the process of completing the study in the future because we learn it as a foundation now. (Minjae)

In middle school or high school, we prepared for the Korean Scholastic Ability Test by answering multiple-choice questions, so what we needed back then was not academic writing skills. But we need them now. (Joonsu)

Participants also cited the usefulness of academic English writing, considering that the content taught in academic English writing classes is practically useful because it helps them unfold their thoughts not in whatever format they please but according to academic standards. They seemed to be aware that writing in English according to the academic format is the matter at hand as they enter the university; thus, it becomes “practical” and “real” knowledge that they can make good use of during their university life. The appropriateness of mandatory academic English writing training was also found in the future- oriented nature of academic English writing skills. Some students saw that academic English writing skills will be needed in the future, particularly when they will have to read a lot of English academic journals and write a thesis in English at the end of their school year, so learning these useful skills in advance was still beneficial. Participants also noted the value of the transferable nature of academic English writing. The knowledge they gained in an academic English writing class could be applied not only to English study, but also to various fields of study. Respondents mentioned that knowledge about how to write academically in English would also make their Korean writing better and help them read major textbooks in English. Since what they learn would transfer beyond an academic English writing class itself, it was regarded as appropriate to make it a mandatory general English course at university.

The last reason was related to the rarity of the opportunity to learn academic English writing. Despite its importance and usefulness during their university life, some students acknowledged that they had not seen any classes where they could learn academic English writing systematically in particular. It might be possible to find university elective courses or rely on private academies to learn about it, but there was a concern that it would be “burdensome.” In this matter, Yuna commented that there could be even a backlash from students if the school just sat on their hands and shifted all responsibility to develop these skills only to the students:

How to write academic writing in English could also be learned by taking an elective course or attending a private academy, but for many students, investing even their extra time in finding where to learn academic English writing rather than in focusing on their major can be discouraging. However, if it is taught as a required course, there will be less burden on students in their time management.

5. Conclusion and Implications

The present study set out to examine how college students responded to their learning experiences in an English writing course for academic purposes. It also sought to assess their view of the appropriateness of academic English writing in the Korean higher education context. The findings reveal that the vast majority of the participants held a positive view of the class for three main reasons. First, students were satisfied with the course content, such as essay structure, in-text citation, reference, and writing mechanics, which they believed would help them to write more “academically” and “professionally” in English. Participants stated that the course content will be of great use later when they have to produce an academic paper, such as a thesis. They were also impressed with the novelty of the course since they had seldom experienced learning how to write an academic paper in their previous English classes. Second, the students were satisfied with the class due to the sense of achievement they experienced. That is, they felt that they learned a lot and gained essential knowledge about academic English writing despite the demanding nature of the course, which created positive feelings about themselves. The last reason identified was the instructor’s teaching style. The students stated that the instructor’s support for their learning through feedback and guidance and her way of organizing the class efficiently assisted them to successfully complete the course.

Reasons for students’ dissatisfaction with the class were also examined. For some students, the novelty of the course content was perceived as a drawback of the class in that they had great difficulty learning it. The fact that the primary medium of the instruction was English appeared to exacerbate the difficulty. In addition, students felt burdened by too much content and heavy assignments for a two-hour, two-credit course.

In terms of their writing, although the number of students who strongly agreed was relatively low compared to those who agreed, participants felt that their English writing had improved overall by the end of the course. More students reported that they became able to complete a paragraph and/or an essay writing better than before they took the class. Among the activities conducted over the semester, students chose essay writing, APA style and in-text citations, and instructor’s lectures and feedback as being most helpful for improving their writing skills. Compared to these, paragraph writing and in-class group writing activities were favored by a relatively smaller number of students. Difficulties students had with the class overlapped with their reasons for being dissatisfied. In light of difficulties with the academic writing skills, citing and referencing in APA style and developing paragraphs or essays in a logical order were most noticeably mentioned by the students.

Students’ perception of the appropriateness of offering academic English writing as a mandatory general education course was also explored. Participants believed that Korean university students need output-oriented English classes such as speaking and writing, and they expected a writing class to result in immediate improvement in a learning environment where a limited time is allowed. Students expressed strong agreement that an academic English writing class would be useful for their academic activities across various academic fields, not to mention in their own discipline. However, there were relatively low agreement rates for employment preparation and job performance at work.

A majority of participants considered academic English writing suitable for a required course for several reasons. To begin with, they recognized academic English writing as essential knowledge for a university student. This implies that students were starting to develop an identity as a member of an academic discourse community in the process of encountering and practicing its specific genres and rules (Jwa & Ha, 2020). Students also pointed out its practicality in their own studies, meaning that they expected to utilize the skill for their academic activities especially in their later undergraduate study when they would have to read a lot of English textbooks and write a thesis in English. On top of that, students recognized academic English writing as transferable knowledge which is needed not only in English class but also in other fields of study. Lastly, students mentioned that there is little chance of learning academic English writing anywhere else in spite of its necessity, which justifies offering it as a part of the required general education curriculum at university.

On the basis of the findings of this study, some suggestions can be made for both school administrators and individual instructors. Considering that the course content was mentioned as the reason for both students’ satisfaction for the academic English writing course and its suitability as a mandatory subject at college, school administrators should consider it as an integral part of general education at college. It also seems desirable to allocate more class time for an academic English writing course by either increasing credit hours or offering two semesters of the course. Participants repeatedly noted time constraints in their answers to the survey and interview questions, not to mention too much content and too many assignments for a two-credit course.

In terms of helpful activities for improving their academic writing skills, more students chose essay writing than paragraph writing since they felt that more time was spent on the former, so that they could write a well-thought- out piece. In a similar vein, students felt in-class group writing was not effective due to lack of time given to achieve the task. These all indicate that expanding credit or class hours can lead to more satisfying and successful learning experiences for students.

Next, schools may weigh the possibility of offering an academic English course to students in their sophomore or junior year. Participants in this study were first-year students who seemed to hold a futuristic view of the applicability of academic English writing skills, believing that they will be useful “later” when they need to write a paper in English or read more English textbooks. Students’ value and motivation for learning academic English might increase if they are exposed to it when the skill is needed in the present or immediate future.

Lastly, schools ought to provide various elective English courses or extracurricular programs for the subject. For example, various bridging courses can benefit students, especially those who do not have adequate English proficiency to take an academic English writing course. In view of the relatively low certainty about the usefulness of the course for their job preparation and job-related skills, elective courses and/or extracurricular programs that focus on job interview skills or English for specific occupations can meet students’ various needs and offer a general English program in a balanced way as a whole.

Instructors are recommended to make an effort to identify students’ needs and challenges. Instructors ought to carefully examine the circumstances students are in and then make a decision about the amount and progress of course content and assignments and the main medium of the language used in class. This tailored instruction will result in lessening students’ burden and possibly yield better learning outcomes. Instructors should also consider providing extra learning materials, such as pre-recorded short video lectures on important academic writing skills. For example, APA style was frequently mentioned by participants as one of the most challenging contents to grasp because of its unfamiliarity and complexity. Such aids will help students become familiar with new and difficult content and make it easier for them to apply it in their own academic English writing. Instructors can also design their writing class in a way that students learn “tangible” writing skills that they can actually use in their writing and produce “tangible” learning outcomes by which they can check on their actual development so they can feel a stronger sense of achievement, which is more likely to increase their satisfaction.

With regard to the limitations of this study, the case study approach means that this study was conducted in the context of writing-focused EFL classes for first-year students in one Korean university taught by one instructor. Therefore, generalization of these findings should be made with caution since they might not be germane to other cases. For example, different results are possible if the same course is offered to students at different levels of English proficiency, to students attending more or less academically rigorous universities in Korea, or to students in junior or higher years who have already acquired specific knowledge in their discipline. Given the limitations of the current study, future studies should expand to other contexts with varied factors. The current study could serve as a baseline for such future research directions that will contribute to developing academic English writing programs that can prepare Korean college EFL learners for increasingly globalized educational and professional settings.