Examining Korean Students’ Self-Directed English Learning Practices in General English Classes at College

대학 교양영어 수업에서 실시된 자기주도영어학습 프로젝트에 관한 학생의 경험과 인식 조사

Article information

Abstract

Abstract

This case study examines Korean college students’ self-directed English learning practices performed outside of the classroom. In particular, the current study investigates what learning activities the students choose and carry out for their self-directed learning (SDL) and how they respond to the project as part of a general English course. Based on Knowles’ (1975) conceptualization of the process that autonomous learners go through, the self-directed English learning project proceeded in five phases: reflecting on students’ own previous English learning experience, researching information about how to study English and what English learning materials to use, designing their own English learning plans, executing the plans, and reflecting on their SDL practices.

Students from two general English classes engaged in the SDL project for 13 weeks during the Fall semester of 2019, and a total of 51 students participated in this study. The main source of data was survey questionnaires administered during the project, which consisted of multiple-choice, 5-point Likert scale, and open-ended questions. As supplementary data, the students’ study logs and the instructor’s teaching materials were also collected. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze and display responses to the multiple-choice questions and Likert-scale ratings. Qualitative analysis was used for students’ responses to the open-ended questions to identify common themes among students.

Analysis of the data revealed that the students most often chose input-oriented activities focusing on listening and reading as opposed to speaking, which was the area of English they most wished to improve. Depending on the area of English, learning materials were chosen differently, and speaking/writing activities were mostly conducted individually. In general, smartphones were preferred, but for those who used English learning sources designed for educational purposes, traditional tools like print books were preferred. The students showed overall positive responses to the SDL project and reported that it allowed them to have a new experience with English learning, to discover various English learning methods, and to improve their English ability. However, some difficulties carrying out the project were mentioned by the students, including the time to make for the project and the overall effectiveness regarding their English learning activities.

The findings of the study indicate that the SDL project can positively impact students’ English learning by preparing them to be more autonomous English learners. The findings also suggest that both individual instructors and institutions should provide students with further assistance and scaffolding to support their self-directed English learning. Instructors are recommended to take advisory roles and offer appropriate assistance and guidance for their students to have successful SDL experiences and develop their SDL capacity in sustainable ways. In addition, institutional level supports such as various English learning environments, one-on-one consultation services, and extracurricular programs are suggested as effective ways to facilitate students’ self-directed language learning.

Trans Abstract

초록

본 연구의 목적은 대학 교양영어 수업에서 자기주도영어학습 프로젝트를 통해 학생들이 어떤 영어학습 활동을 계획하고 실행하는지 그리고 본인의 자기주도영어학습 활동에 대해 어떻게 인식하고 있는지를 조사하는 데 있다. Knowles(1975)가 제안한 자기주도학습자들이 겪는 학습 과정을 기반으로 자기주도영어학습 프로젝트는 먼저 기존 영어학습 활동에 관한 고찰, 영어학습 방법과 영어학습 자료에 관한 조사, 영어학습계획 설계, 영어학습계획 실행, 그리고 자신의 자기주도영어학습 프로젝트에 관한 고찰 순으로 진행되었다.

2019학년도 2학기 교양영어 강좌 두 개 분반에서 총 69명의 학생이 교양영어 과목 과제의 형식으로 자기주도학습 프로젝트에 13주 동안 참여하였으며, 그중 51명이 본 연구의 주요 자료 수집 방법인 설문에 참여하였다. 설문은 선다형, 리커트 5점 척도, 개방형 질문으로 구성되었다. 또한, 학생들의 학습일지와 교수자의 수업자료 등의 보조자료가 수집되었다. 선다형 질문과 리커트 5점 척도 질문에 대한 답변을 분석하고 서술하기 위해 기술통계가 사용되었으며, 개방형 질문에 대한 답변에서 공통된 주제들을 찾기 위해 질적 자료 분석 방법이 사용되었다.

자료 분석 결과, 학생들은 듣기와 독해에 초점을 둔 입력 기반 영어학습 활동을 주로 선택하였으며 이는 학생들이 프로젝트 시작 전 가장 많이 희망했던 말하기 학습과는 다소 상반관 결과를 보여주었다. 또한 영어학습 영역에 따라 학습 자료의 선택이 다르게 나타났으며, 말하기/쓰기 영역의 경우 영어학습 활동이 개인 학습 형식으로 국한되어 나타났다. 그리고 학습 도구의 경우 전반적으로 스마트폰을 선호하였으나 교육용 학습자료를 사용하는 학생은 종이책과 같은 전통적 도구를 선호하였다. 본 프로젝트에 관해 학생들은 새로운 영어학습 경험, 다양한 영어학습 방법 습득, 영어 실력 향상 등 대체로 긍정적인 반응을 보였으나 꾸준히 프로젝트를 실행하는 것과 프로젝트를 위한 시간 할애 그리고 자신의 영어학습 활동에 대한 불확실성 등에서 오는 어려움 또한 언급하였다.

본 연구는 자기주도영어학습 프로젝트를 통한 영어학습자의 자기주도적 영어학습에 대한 긍정적인 영향 가능성을 보여주었다. 하지만, 학생들의 성공적인 자기주도적 영어학습을 위해서는 교수자 개인뿐만 아니라 학교 기관 단위의 노력이 필요함 또한 시사하고 있다. 우선, 교수자는 학생들이 좀 더 효과적인 자기주도 영어학습을 경험하고 지속할 수 있도록 자기분석, 학습 목표 및 계획 수립, 학습자료 선정 등에 지도 및 조언을 제공해 줄 수 있을 것이다. 학교 기관 차원에서는 다양한 영어학습환경, 일대일 상담 서비스, 비교과프로그램 등을 확충함으로써 학생들의 자기주도 영어학습을 지원할 수 있을 것이다.

1. Introduction

Many Korean college students strive to increase their English ability, which is regarded as necessary for better employment opportunities. However, some studies indicate that taking compulsory general English classes in college is not sufficient for students to improve their English proficiency in terms of both time and content (e.g., Kang & Oh, 2013). Briggs and Sherman (2018) revealed that a college student spends approximately 45 hours per semester in an English course, which is merely one third of the time that the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) estimates a language learner needs to advance one proficiency level on a six-level scale. Despite the lack of time, however, some colleges have decided to reduce the number of compulsory credit-bearing English courses they offer. This situation is also related to students’ dissatisfaction with general English course contents that fail to meet their specific needs (e.g., raising certified English test scores) (Seo, 2018). As such, it is imperative for Korean college students to invest time and effort out of class in order to advance their English proficiency. In other words, they cannot solely depend on teacher-directed English learning in class, but they must take ownership of their learning, deciding their own learning goals and the ways to meet them. This means Korean college students need to develop self-directed learning (SDL) skills built on autonomy and responsibility (Knowles, 1975).

In spite of the significance of developing the learner’s responsibility for SDL, Korean students tend to be quite passive in their English learning, which can be partially explained by the fact that they have no choice but to study English as part of the school curriculum (Kim & Kim, 2009). Throughout their English education in secondary and tertiary levels either in public or private sectors, they are instructed with a teacher-centered and exam-oriented structured curriculum, which makes it difficult to exercise autonomy and practice their responsibility as learners in the real world (Hwang, 2011).

This suggests that developing learner autonomy needs to receive more attention and should be emphasized as a learning goal for English learners in tertiary education, where there is more flexibility compared to secondary school classrooms. In other words, Korean college students should be supported and guided to become autonomous learners who can actively engage in planning, executing, and evaluating their English learning out of class (Knowles, 1975). However, the current literature on SDL for Korean college EFL students focuses on directives given inside formal classrooms rather than on their independent English learning in informal environments.

In order to fill this void in the current literature, this study offers a case of a general English class in college in which students participated in a supplementary activity where they experienced out-of-class SDL practices. In particular, the purpose of the study is to identify the students’ English learning practices when a class project is introduced to promote self-directed English learning and to understand how they respond to the project. The research questions that guided this study are:

1) What learning activities do college students do when they are instructed to develop and carry out their own self-directed learning plans?

2) How do college students perceive their self-directed English learning practices?

2. Literature Review

2.1 Self-directed Learning (SDL) and Language Learning

Self-directed learning (SDL) refers to a “[l]earner’s autonomous ability to manage his or her own learning process, by perceiving oneself as the source of one’s own actions and decisions as a responsibility towards one’s own lifelong learning” (Foo & Hussain, 2010, p. 1913). The term “autonomous learning” is quite often used in connection with SDL. Some (e.g., Gremmo & Riley, 1995) distinguish “autonomy” as a capacity from SDL as a way in which learning is carried out. In this paper, however, the terms SDL and autonomous learning are used interchangeably.

SDL has received a lot of attention especially in the field of adult education since the 1970s. One of the contributions of SDL is that it has shifted the focus of education and the learning process from teacher-directed to learner- or self-controlled (Candy, 1991), so that learners are expected to take responsibility for their own learning. According to Knowles (1975), the autonomous learner goes through different processes while engaging in SDL:

Individuals take the initiative, with or without the help of others, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating learning goals, identifying human and material resources for learning, choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies, and evaluating learning outcomes. (p. 18)

In order to successfully engage in SDL, Knowles asserts that it is necessary for students to develop skills, competencies, and emotional maturity. Knowles also states that autonomous learners tend to invest in their learning and are therefore likely to have a more successful learning experience.

Over the past decades, learner autonomy has been extensively discussed in the field of education; language education is no exception. Many researchers (e.g. Benson, 2006; Cotterall & Crabbe, 1999) have recognized that a major goal in language education should be to foster learner autonomy. In line with Knowles’ assertion, language learners with SDL skills can reach their learning goals successfully since they tend to focus on the skill areas they need to improve in order to meet their language learning goals (Reinders, 2010). They are more invested in their learning by practicing the language skill autonomously everywhere and anytime, whether in or out of class (Benson 2009).

Some researchers have aimed to illuminate the relationship between L2 learners’ level of autonomy and their language proficiency. For example, Dafei (2007) studied Chinese EFL students and found that their autonomy level correlated significantly with their English proficiency scores. This finding implies that the more autonomous language learners become, the more they can expect to attain higher levels of language proficiency.

Mineishi (2010) investigated differences between Japanese English language learners with higher and with lower proficiency in terms of their perception of learner autonomy. Compared to learners with higher levels of English proficiency, their counterparts were less likely to work independently, express their opinions, ask questions, and take responsibility for evaluating their learning progress. These findings also support the idea that more proficient language learners are likely to be more autonomous.

Little (1997) stated that learner autonomy is not inborn but can be acquired by training. Similarly, Reinders (2010) asserted that students will need training and support to become autonomous learners. In other words, language teachers should help their students to realize their potential for SDL. Humphreys and Wyatt (2014) found that giving students opportunities to share their learning experiences increased their sense of autonomy. Through these kinds of reflective activities, they were able to cultivate more active, independent attitudes toward their language learning. The results proved that socially mediated support from teachers and peers is necessary for language learners to increase control and responsibility over their learning. Their findings demonstrated the significance of providing learners with learning activities and environments that will enable them to develop autonomous learning like the one that this study attempted to.

2.2 Korean EFL College Students’ Autonomous Learning

Although SDL was originally conceptualized for adult learners (Knowles, 1975), most previous SDL studies in Korea have been conducted in primary or secondary education rather than tertiary education. A limited number of studies have been conducted to examine college EFL students’ SDL in Korea, most of which have focused on the influence of blended learning or flipped learning on SDL since both approaches are student-centered and involve students’ independent learning process.

Bang (2006) examined the effects of implementing SDL by creating a homepage for the students enrolled in a college English reading class. The SDL group engaged in individual learning activities through the homepage, where they had access to information about the reading that they would discuss in class and various types of additional materials they could choose depending on their proficiency levels and interests. Then, the students engaged in discussions of the readings instead of traditional lectures in an offline class. The results showed that the SDL group outperformed the traditional teacher-centered learning group in terms of test scores. Moreover, Bang reported that students in the SDL group perceived SDL to increase their motivation since they were able to realize the areas they needed to improve in and to select the materials according to their interests on the homepage. Based on these findings, Bang emphasized the effectiveness of SDL utilizing technology.

More recently, Jung (2017) examined the effect of a flipped learning class on improving 93 college students’ SDL competences for one semester. The findings showed that the experimental group who engaged with flipped learning significantly enhanced their SDL capacity compared to the control group without flipped learning. In particular, the experimental group improved in identifying learning goals, resources, and strategies. Based on these findings, Jung concluded that the flipped learning approach promotes active and student-centered learning, which fosters learners’ SDL skills.

Another example of research investigating SDL in a blended learning environment is Lee and Cho (2017)’s study on 28 Korean college students who took part in an English coaching program for 13 weeks. The participants practiced English speaking using computer software on their own and then met with a coach who asked questions related to the content they studied. The students were also required to keep a weekly journal to reflect upon their learning experiences and SDL. The findings showed that they improved their speaking skills but not their SDL competences. From these findings, the researchers emphasized the need for more studies on programs which deal with developing language learners’ autonomous learning capacity, not just their language skills.

As the studies described above indicate, most research on Korean EFL college students’ SDL was conducted in conditions where blended learning was implemented as a part of a formal class. Even though this line of studies proved that blended learning has positive effects on students’ autonomous learning, what the previous literature misses is how Korean EFL learners’ autonomous learning is fostered with support and guidance to improve their own awareness and understanding of it. In addition, much research (including the studies reviewed above) focuses on formal EFL classrooms rather than college students’ informal independent English learning outside of classrooms.

There have been a few studies that attempted to address these gaps. Oh (2005) conducted action research on a group of Korean college students’ autonomous English learning practice as she assisted them to become more self-directed English learners. In order to foster students’ autonomous English learning, she included various activities in the course, such as sharing her personal experiences as an English learner, using autonomy-fostering games, and managing an online discussion forum to facilitate their out-of-class English learning. Findings revealed that the students who were originally active in their English learning became more autonomous as the semester progressed, and three initially less-active students became autonomous at a slow pace. Based on these findings, Oh argued that autonomy-fostering approaches can work positively for students but need to be implemented based on students’ initial autonomy levels.

Shim (2008) investigated 25 college students’ SDL practices out of class. Employing a qualitative research method, she collected the participants’ reflective journals on their English learning experiences for one semester. The students’ motivation influenced by various contextual factors, such as chances to realize the importance and societal values of English proficiency and learning strategies based on their metacognitive knowledge, turned out to be two prominent factors influencing their SDL. Based on these results, Shim recommended that universities need to support and promote their students’ SDL.

Oh’s (2005) and Shim’s (2008) studies are significant in that they demonstrated how learner autonomy can be promoted and facilitated for Korean EFL college students. However, there is still a paucity of research on how to help students be more autonomous English language learners. In order to fill this gap, this study examines two college-level general English classes in which an SDL project to develop and support the students’ autonomous English learning was implemented. In particular, the current research focuses on how the students created and utilized English learning opportunities out of class. Furthermore, by examining their views and perceptions toward the SDL activity, this study strives to provide meaningful insights about promoting autonomy among language learners.

3. Methods

3.1 Research Context

This research was conducted in two general English classes at a four-year university in Korea in the Fall semester of 2019. The classes were taught by one of the researchers of this study, and each of the classes met once a week for two hours over the 15-week semester. The curriculum focused on English reading and writing. The two classes had 33 and 36 registered students, respectively. The students were classified as beginner-level learners of English based on the results of a placement test administered before the school year started. The classes were mixed with students from different years, but the majority were first-year students (81%). Majors included Engineering (53.6%), Law (18.8%), Humanities (10.1%), Business (7.2%), Korean Language (5.8%), and Social Science (4.3%).

A self-directed English learning project was introduced as a type of homework activity which counted for 10% of the whole grade. In this activity, students were instructed to design and carry out their own SDL plan throughout the semester. The project aimed to support and guide the students as they tried out English skills they wanted to improve, employing learning materials and methods of their own choice and to help them become more autonomous English learners who would continue to strive to advance their language proficiency with ownership and responsibility for their learning.

Inspired by Knowles’ (1975) conceptualization of the process that autonomous learners go through, the self-directed English learning project proceeded in five steps: reflection, research, practice, report, and reflection (Table 1). The project started off with a survey questionnaire (Survey 1) inquiring about students’ past and current English learning practices since entering university. Survey 1 was a part of the data for this study, but it was also an important component of the self-directed English learning project in that it provided students with time to think about their own previous English learning experience and think about their needs and goals for English learning. In week 3, the results of the survey were shared in class.

In weeks 3 and 4, the students were given time to design their plan while researching the best ways to improve their English as homework and discuss in class what they wanted to do in order to reach their goal and what learning materials and methods they wanted to try. Starting in week 5, each student executed their plan at their own pace up until week 12 except for the midterm exam week. In weeks 8 and 13, the students were required to submit their study logs to the instructor for the interim and final check-ups, respectively. In week 13, they were asked to complete a survey (Survey 2) designed to help them to reflect on their own self-directed English learning practices. The results of Survey 2 were also shared in class in week 14.

There was no restriction in their choice of English skills, learning materials, and learning methods. Instead, there were only minimum guidelines: the students were required to engage in their learning activities on a daily basis for 20-30 minutes each day, five days a week, to keep a log recording their learning activities on paper, and to submit the log two times, in the middle and by the end of the semester.

The second author of this study was the instructor of the two classes. As a teacher, his main role in the project was to encourage the students to consistently complete their SDL tasks by posting reminders about the project on the classroom management system and to spend about 5-10 minutes on a weekly basis checking their learning progress in the classroom. As a researcher, however, he remained distant from the students, particularly when they identified their English learning needs and goals and searched for English learning resources and strategies, so that his presence would not influence their decision about what to study and how.

3.2 Participants

Fifty out of 69 students from the two mandatory general English classes participated in Survey 1. Survey 1 was developed to collect students’ background information and their past and present English learning experience. Four fifths of the participants were first-year students, and the rest were two sophomores, one junior, and five seniors. Twenty-nine students were studying Engineering, 12 Humanities, 4 Law, 3 Business, and 2 Social Science.

According to the result of Survey 1, three fourths of the students (76%) said that they had not had the experience of making and carrying out plans for their English learning since they entered the university. In addition, 30 out of 50 students (60%) responded that they spent zero minutes learning English, four students about 30 minutes, 10 students about one hour, and 6 students about two hours during the summer break right before the fall semester of 2019 when this research was conducted. For those 20 students who spent time learning English during the summer break, “listening” was the area of English that they worked on the most (40%), followed by “reading” (35%), “speaking,” (25%) and “writing” (20%). To the question whether they were engaging in English learning activities other than those in the current general English class, the majority of the students (78%) responded that they were not.

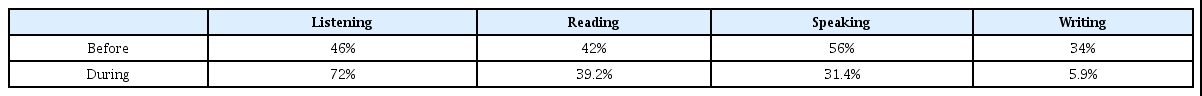

In contrast to the students’ small investment of time and effort in English learning since they entered the university, they were well aware of their need to learn English: more than four fifths (86%) of the students agreed or strongly agreed that learning English is important in their college life, and only one deemed English unimportant. In addition, when asked whether they agree that taking mandatory general English courses provided by the school is enough to improve their English proficiency, only 14% of the students agreed; more than half of the students (60%) said that these classes are not enough. In terms of willingness to invest their time in English learning during the present semester, 70% responded they were willing to, 28% were not sure, and 2% were not willing to. For many students, “speaking” (56%) was the language area/skill they wanted to focus on the most, followed by “listening” (46%), “reading” (42%), and “writing” (34%).

In summary, the results of Survey 1 show that many students did not consider English learning practices except for taking a mandatory general English class to be part of their college life even though they were aware of the importance of improving their English and the need to spend additional time in order to do so. In addition, the students wanted to work on several areas of English during the semester, but many showed a strong interest in speaking.

3.3 Data Collection

Two surveys were conducted in week 2 and week 14, respectively. Participation in the surveys were voluntary and anonymous. Survey 1 focused on collecting students’ background information and finding out their English learning experience before the SDL project started, and Survey 2 asked about students’ own experience with the SDL project and their perceptions about it. The questions were developed in Google Forms and links were posted on the online classroom management system, so that the students did not feel compelled to participate. In total, 50 out of 69 students completed the Survey 1 questions, and 51 out of 69 did the Survey 2 questions. The surveys consisted of multiple-choice, 5-point Likert scale, and open-ended questions. Because the research was targeted toward Korean university students, all the questions were written and answered in Korean, but they were all translated into English later for this article (Appendix A).

In addition to the surveys, the instructor’s weekly postings uploaded on a classroom management system and the students’ study logs were collected and reviewed. Although those supplementary data did not work to directly answer the research questions, they were essential to keep track of the SDL project and to better understand students’ SDL activities.

3.4 Data Analysis

The surveys were conducted in Google Forms, so participants’ answers were automatically transformed into Excel data. Since this research was a small-scale study, descriptive statistics were used to analyze and display responses to the multiple-choice questions and Likert-scale ratings. The researchers decided to use percentages rather than mean scores in order to take a closer look at how responses to each answer are distributed not only within a question but also between questions; this expanded the possibilities of other analyses. Cronbach’s alpha was used to estimate internal consistency reliability for the benefits of the SDL project (i.e., items 9, 10, 11, and 12 of Survey 2); the reliability was .77.

For the open-ended questions, both researchers read students’ responses individually, identified emerging themes by grouping similar responses, arranged them in the order of frequency, and discussed their findings until they reached agreement. In some cases, the researchers placed two different questions and their responses side by side in order to examine any correlations between them. Although students’ study logs did not function as primary data resources, they were arranged under the categories of “what” area(s) of English and “how” it/they was/were learned. The summaries of students’ study logs were compared later with survey responses to identify any discrepancies.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1 Students’ Self-Directed Learning Activities

Survey 2 started with a question (Question 1) asking about English learning activities that students worked on for their SDL project. Examples of these activities are listed in Table 2. In terms of areas of English, listening turned out to be the area the students chose to work on the most (72.5%), followed by reading (39.2%), speaking (31.4%), and writing (5.9%). When this result is compared to the students’ responses to Question 9 in Survey 1 asking what areas of English they want to focus on during the semester, distinctive differences were found in two ways (Table 3). First, listening was chosen the most (56%) as the area that the students wanted to work on, but listening was practiced the most when the project was implemented. Secondly, 34% of the students responded that they wanted to study writing, but the number of students who actually chose to practice writing was only 5.9%.

The responses to Question 1 also show that about half of the students (26 out of 51) included more than two areas of English in their SDL project as follows: 15 listening and speaking activities (e.g., practicing shadowing or using English conversation apps), 10 reading and listening (e.g., studying reading and listening parts of the TOEIC test), and 2 listening and writing (e.g., writing summaries of English dramas after watching them). The other half of the students (25 out of 51) included only one area of English: 10 students worked on listening, 10 reading, 1 speaking, 1 writing, and 5 focused on vocabulary learning in isolation.

The types of English learning areas are presented in Figure 1. Most of the students integrated English listening into their SDL project, and various types of listening materials were used such as TOEIC listening questions, English conversations made for educational purposes, YouTube videos, movies, and dramas. On the other hand, when it comes to reading, the majority of students (17 out of 20) chose TOEIC reading texts as their reading materials rather than authentic materials like novels and magazines. Another interesting pattern is that speaking was practiced mostly with listening, not with the other areas of English. Next, no combinations of reading and speaking, reading and writing, or speaking and writing were found in the students’ SDL activities. Lastly, when reading and listening were combined, the practices of each area took place in an isolated way; that is, reading activities did not lead to listening activities or vice versa with some commonality in terms of their learning contents.

Question 2 asked on what basis the students chose their own SDL activities. Thirty (58.5%) students responded that their prior English learning experience played an important role in their decision-making process. The next most frequently mentioned was a classroom activity to research English learning methods online (33.3%), followed by classroom discussions with classmates (7.8%) and the instructor (5.9%). For some students (13.7%), external sources of information (e.g., media, private language institutes, and library) worked as an influential factor. Although these results show that students’ own English learning experience is still the number one factor, this does not mean that the class activities that the instructor included to facilitate the SDL project (i.e., finding learning methods on YouTube and classroom discussions) failed to help students to think more about their language learning practices. In fact, among 30 students who identified their previous English learning experience, 11 also selected one of the class activities. Thus, in total, there were 24 students who found that the class activities influenced their decision, which is more than the 17 students who responded that they only relied on their learning experience when they made a choice.

In Question 3, the students were asked what they took into consideration when coming up with their own SDL activities. The result shows that whether an activity is easy to carry out was considered the most (45.1%), followed by how helpful it is for English learning (37.3%) and how much fun it will be to do (31.4%).

Question 4 asked participants to identify the type of learning material they mainly used for the project. A total of 26 students (51%) chose contents that were specifically made for educational purposes (i.e., contents designed for general English learning and English test prep contents), while the other 25 (49%) chose general English contents (i.e., visual media contents like YouTube videos, films, and TV shows and reading contents like newspapers).

When it comes to the types of learning tools that students used (Question 5), 26 students chose to use digital tools (e.g., smartphones and computers), 13 used traditional tools like paper books or CD players, and 9 used both. No one chose TV or radio as a platform for their learning. Although many students chose digital tools, there was a clear difference in the types of learning tools between those who used non-educational English learning materials and those who used educational English contents as shown in Figure 2. In general, the former used more digital tools like smartphones and computers, and the latter used more print-based books.

As for the reasons why they made their choice, the answers to Question 6 show that those who preferred to use digital tools tended to point out their technical advantages. For example, smartphones are used and carried every day, are able to play videos, make it easy to access learning contents through various apps, and are not restricted to time and place. Computers make it easier to browse, find, and use learning materials and are more comfortable when playing videos due to their larger screen. On the other hand, those who preferred using paper forms of learning resources pointed out not only their technical advantages in terms of portability and less possibility of eye strain but also their learning efficiency such as increased concentration, less distraction, and ease to remember things. Table 4 lists the reasons why they preferred their own chosen tools.

4.2 Students’ Perceptions on the Self-Directed Learning Project

The second part of Survey 2 is about how the students perceived the SDL project. It started with Question 7, which asked the students to choose features of the SDL project that were helpful for them when undertaking their own project. In general, many students responded that the activities to increase their metacognitive awareness of English learning experience such as reflecting on their past and current English learning activities by answering survey questions (51%) and researching how to learn English online (39.2%) helped them carry out the project. Some students also liked the instructor’s supervision such as providing reminders about the project on- and offline every two weeks (23.5%) and checking their learning logs in the middle of the project (19.6%). On the other hand, only a small number of students (9.8%) responded that the class activity of guiding the students to think about their reasons for learning English and discuss them in class was helpful.

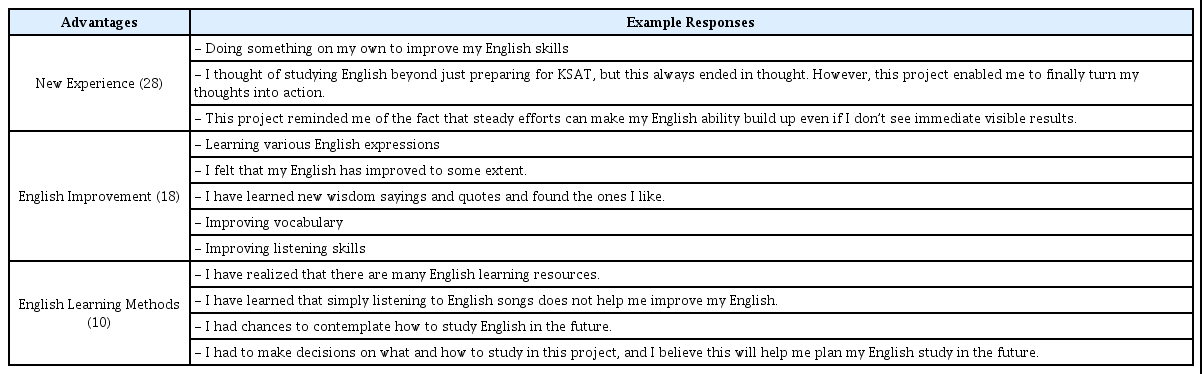

To the open-ended question (Question 8) asking about positive aspects of doing the SDL project, 45 students mentioned at least one of the following three types of advantages: having new experience, gaining ideas about English learning, and experiencing improvement in their English (Table 5). The most reported advantage of doing the SDL project was that the students were able to have a unique experience of learning English. For example, it allowed them to try English learning methods they had always wanted to try but had not due to pressure to succeed on the university entrance exam, and it also gave them an opportunity to try out the learning methods that they were able to find through the project. Some students stated that mandatory English courses do not always fulfill what they desire to learn, but the SDL project made it possible for them to work on the areas of English at the point they needed. In addition, for those who had frequently given up learning English halfway, the SDL project enabled them to experience completing English learning practices on a daily basis all the way to the end of the semester without quitting in the middle. This kind of positive experience through the project eventually reminded them of the importance of consistency in learning English. Secondly, some students felt that they learned some English through the SDL project, ranging from various English expressions, to vocabulary, to listening comprehension, to memorizing well-known sayings in English. Although these might not have led to actual long-term improvement in their English ability, the students believed they enhanced their language skills. Next, through the process of researching and discussing learning methods, some students felt that they ended up with a better idea of how to study English in the future. A few students mentioned that they even learned some lessons about how to learn English through their experience of failing with the SDL project.

The students’ answers to Likert-scale rating questions asking about the benefits of doing the SDL project also support the aforementioned comments to some extent (Figure 3). Question 9 asks whether the SDL project helped their English learning: 56.9% gave positive answers and 5.9% negative ones. In Question 10 about whether the project helped the students to think more about how to learn English, 86.2% agreed or strongly agreed and 5.9% disagreed. Question 11 is about whether the SDL project actually helped them to know more about how to learn English: 62.7% agreed or strongly agreed and 2% disagreed. In Question 12, 53% of the students agreed or strongly agreed that the SDL project helped them to be better prepared for future English learning, but 7.8% disagreed.

Although more students saw positive aspects of the SDL project than negative ones in general, a closer analysis of the data also shows that students lacked complete certainty about its positive influence on their English learning. For example, although no students strongly disagreed with the benefits of the SDL project, few students showed strong agreement. In addition, as shown in Figure 3 that the second highest-numbered choice was “neither agree nor disagree,” more than one third of the students were not certain whether the SDL project benefited their English learning.

The students’ somewhat wishy-washy stance can be partially explained by the difficulties they faced during the SDL project recorded by 41 respondents to Question 13. The difficulties frequently appearing in their responses included making steady efforts, arranging time for the project, and being uncertain about the outcome of their learning activities (Table 6).

First of all, some students had difficulty carrying out the SDL project on a daily basis although the requirement was 20-30 minutes per day. They commented that it was difficult because of their own personal inadequacy, blaming their indolent personality, low sense of purpose for learning English, and/or relative unimportance of English. For some students, it was hard to squeeze the SDL project into their college life due to their busy schedule. They felt short of time to do the SDL project particularly when they had other, more important work to do (e.g., homework from major classes) or were working at a part-time job. The last difficulty was found in their uncertainty about the effectiveness of their own learning activity. For some students, not knowing whether they were on the right track was a demotivating factor. Moreover, the length of the SDL project was not long enough for the students to see the desired results, so they had to continue to carry out the project without knowing its immediate effects, which resulted in their losing an interest in the project.

5. Conclusion

This study investigated Korean college students’ participation in a self-directed English learning project, focusing on their SDL practices outside the classroom and their responses to the project. Although the students seemed to try various types of English learning activities for the project, ranging from studying with TOEIC preparation books to shadowing with English dramas or movies, these were mostly input-oriented activities reflecting the listening and reading areas of English. Many students responded that speaking was the area they wanted to focus on the most, but it was not always the case that their choice of activity matched their desire. One possible reason for this could be that the students had a hard time thinking out of their comfort zones when choosing their English learning activity and simply relied on their previous English learning experience. Another reason could be that they regarded the SDL project as just another homework assignment to do rather than a golden opportunity to improve their English; some students were most concerned about whether activities would be easy to do when they made their SDL plan.

Another notable finding was that students chose various types of both educational and authentic learning materials when the focus was on listening, but few different types of learning materials for reading; these included mostly educational materials and were limited to TOEIC reading texts in particular. When reading was practiced along with other areas of English, it was mostly combined with listening, not with speaking or writing. Even when the students did both reading and listening, their practices were not related to each other. Not only was the number of speaking and writing activities relatively small, but these activities were also restricted to an individual activity style (e.g., writing in a diary, shadowing, and practicing conversational expressions by reading conversation books or using smartphone apps).

Thirdly, the students used smartphones for their SDL project more than other types of electronic tools such as computers, CD players, TVs, or radios. This was mainly due to the smartphone’s technical advantages: they were convenient to use with no time and place restrictions, easy to access because the students use and carry them every day, and capable of playing videos. However, for those who undertook the project with educational learning materials, traditional tools (i.e., paper books) were preferred due to their perceived educational advantages.

The second part of the research was to look into students’ responses to the SDL project. Overall, the students responded to the project positively. They stated that the project provided them with opportunities to have a new experience with English learning such as continuing to learn English without quitting, trying out new ways of learning English, and taking control of what and how to learn. They also pointed out that they were able to discover various English learning methods and have a better grasp of how to study English on their own. Some students even expressed satisfaction with their improvement in English which resulted from making steady efforts to invest their time in English learning outside the class.

However, these benefits were not gained without any difficulties. Some students pointed out that they still had difficulty continuing to carry out the project particularly because of internal reasons such as indolent personality and low motivation. Some students had difficulty when they could not make time for the project due to having important work to do for their other college classes or when they found it hard to check whether their English learning activities were actually working or not.

The findings of the current research highlight some implications for instructors who are interested in creating self-directed English learning opportunities for their students. To begin with, it can be suggested that projects to promote English language learners’ SDL have the potential to serve as a foundation for them to develop learner autonomy, but proper assistance and scaffolding from the instructor should be provided. Many students in this study perceived classroom activities such as reflecting on their previous and current English learning experience, researching information about how to learn English, discussing English learning methods in class, and receiving supervision from the instructor to be especially helpful for them to carry out the SDL project. Nevertheless, although these assistance and scaffolding activities were provided, one third of the students still remained undecided when asked about beneficial aspects of the SDL project, and they were not enough to help the students make changes in their learning practices. Therefore, extended and consistent assistance is recommended through one-on- one interaction between the instructor and students.

In the same vein, instructors should pay closer attention to the students who are less motivated to participate in an SDL project due to internal reasons. As illustrated in the previous section, some students ended up choosing learning activities that were within their comfort zone or that could be easily done or were simply fun to do. This indicates that instructors should take advisory roles and provide their students with guidance to encourage them to try new learning methods and materials that they have never used but are known to be effective, and to balance input-oriented activities with output-oriented ones. In addition, instructors need to educate students to be knowledgeable about how both the technical and educational aspects of each learning tool help language learning so that they can choose learning tools that fit their learning goals, which can eventually lead to their successful English learning experience.

There should be not only individual instructors’ efforts but also institutional support. Despite the importance of instructors’ roles in fostering students’ autonomy, it is not always easy for them to design and integrate SDL activities in their teaching environment due to time and curriculum constraints. Accordingly, extracurricular programs and/or self-access centers should be considered as supplementary approaches to help students’ autonomous language learning. Institutional-level supports including various learning resources and one-on-one consultation services can be effective ways to facilitate students’ self-directed language learning. Extracurricular programs and self-access centers can also offer an environment where students can engage in social interactions with other language learners, which could work to promote output- oriented English learning activities.

As a final note, some of the limitations of the current study should be acknowledged. First, 13 weeks appeared to be not enough time for students to sense the effects of the SDL project on the development of their learner autonomy. In future research, a longitudinal approach of the SDL project will be preferable. Furthermore, adding qualitative research methods could have yielded more in-depth understanding of the students’ SDL practices. For example, students’ learning logs were collected and analyzed as secondary data for the current study, but they were not sufficient to provide detailed descriptions of their SDL practices and their thoughts behind them. Including more data collection methods such as interviews or students’ journals will give a more comprehensive picture of their growth as autonomous language learners.

References

Appendix A

Survey Questionnaires

Survey 1

-

School year: ______________

Major: _______________

-

Have you made plans for your English learning on your own and carried them out since entering university?

1 - Yes 2 - No

-

How much time on average did you spend each day studying English during summer break?

1 – 0

2 - 30 minutes

3 - One hour

4 - One hour and 30 minutes

5 - Two hours

6 - Three hours

7 - Four hours or more

-

If you studied English during summer break, what area of English did you focus on? Please check all that apply.

1 - I didn’t study English at all

2 – Listening

3 – Reading

4 – Writing

5 - Speaking

-

Are you studying English on your own besides taking general English classes?

1 - Yes 2 - No

-

Do you agree that studying English is important in college life?

1 - Strongly disagree

2 – Disagree

3 - Neither disagree nor agree

4 – Agree

5 - Strongly agree

-

Do you agree that taking general English classes is enough to improve your English skills?

1 - Strongly disagree

2 – Disagree

3 - Neither disagree nor agree

4 – Agree

5 - Strongly agree

-

How interested are you in investing your time to improve your English skills?

1 - Very disinterested

2 - Somewhat disinterested

3 - Neither disinterested nor interested

4 - Somewhat interested

5 - Very interested

-

What area of English would you like to focus on in order to improve your English skills? Please check all that apply.

1 – Listening

2 – Reading

3 – Writing

4 - Speaking

Survey 2

-

What area of English did you focus on in order to improve your English skills? Please check all that apply.

1 – Listening

2 – Reading

3 – Writing

4 – Speaking

5 - Other

1-1. What was your choice of method for studying English in this semester’s self-directed learning project?

(e.g., practicing English speaking while watching dramas in English and studying TOEIC reading parts)

-

Who or what influenced your choice of method? Please check all that apply.

1 - My previous experience

2 - The assignment to research how to study English online (e.g., on YouTube or blogs)

3 - What the professor said during in-class discussion

4 - What the classmates said during in-class discussion

5 - School seniors’ advice

6 - Someone else’s advice

7 - Private institute

8 - Various types of media

9- Other

-

What did you consider when choosing the method? Please check all that apply.

1 - Whether it will really help me improve my English skills

2 - Whether I can have fun doing it

3 - Whether it is easy enough to do it

4 - Whether it is easy to receive a good score from doing it

5 - Whether I can do it steadily

6 - Other

-

What kinds of learning materials did you use?

1 - Contents made for English learning purposes (e.g., textbooks or media made for English learning purposes or for English language test preparation)

2 - General English contents (e.g., mass media contents, YouTube contents, and newspapers)

-

What tool(s) did you use for studying English?

1 - Smartphone apps

2 - Computer

3 - TV

4 - Paper-based books

5 - Radio

6 - Other

What was the main reason why you chose the tool(s) you mentioned in Question 5?

-

Which feature of the project helped you with your self-directed learning project?

1 - Discussing reasons for learning English in class

2 - Researching different English learning methods on YouTube and sharing them in class

3 - The professor’s bi-weekly reminders on the project (in-class or through E-learning)

4 - Reflecting on my English learning through answering survey questions like this

5 - Having my learning progress checked in the middle of the project

What were you able to gain through this project? (Things that you liked about it)

-

Did this project help your English learning?

1 - Strongly disagree

2 - Disagree

3 - Neither disagree nor agree

4 - Agree

5 - Strongly agree

-

Did this project help you to think more about English learning methods than before?

1 - Strongly disagree

2 - Disagree

3 - Neither disagree nor agree

4 - Agree

5 - Strongly agree

-

Did this project help you to know more about English learning methods than before?

1 - Strongly disagree

2 - Disagree

3 - Neither disagree nor agree

4 - Agree

5 - Strongly agree

-

Do you feel more prepared for future English learning than before?

1 - Strongly disagree

2 - Disagree

3 - Neither disagree nor agree

4 - Agree

5 - Strongly agree

What difficulties did you have when you carried out your self-directed learning project?

![[Figure 1]](/upload//thumbnails/kjge-2020-14-4-113f1.jpg)

![[Figure 2]](/upload//thumbnails/kjge-2020-14-4-113f2.jpg)

![[Figure 3]](/upload//thumbnails/kjge-2020-14-4-113f3.jpg)